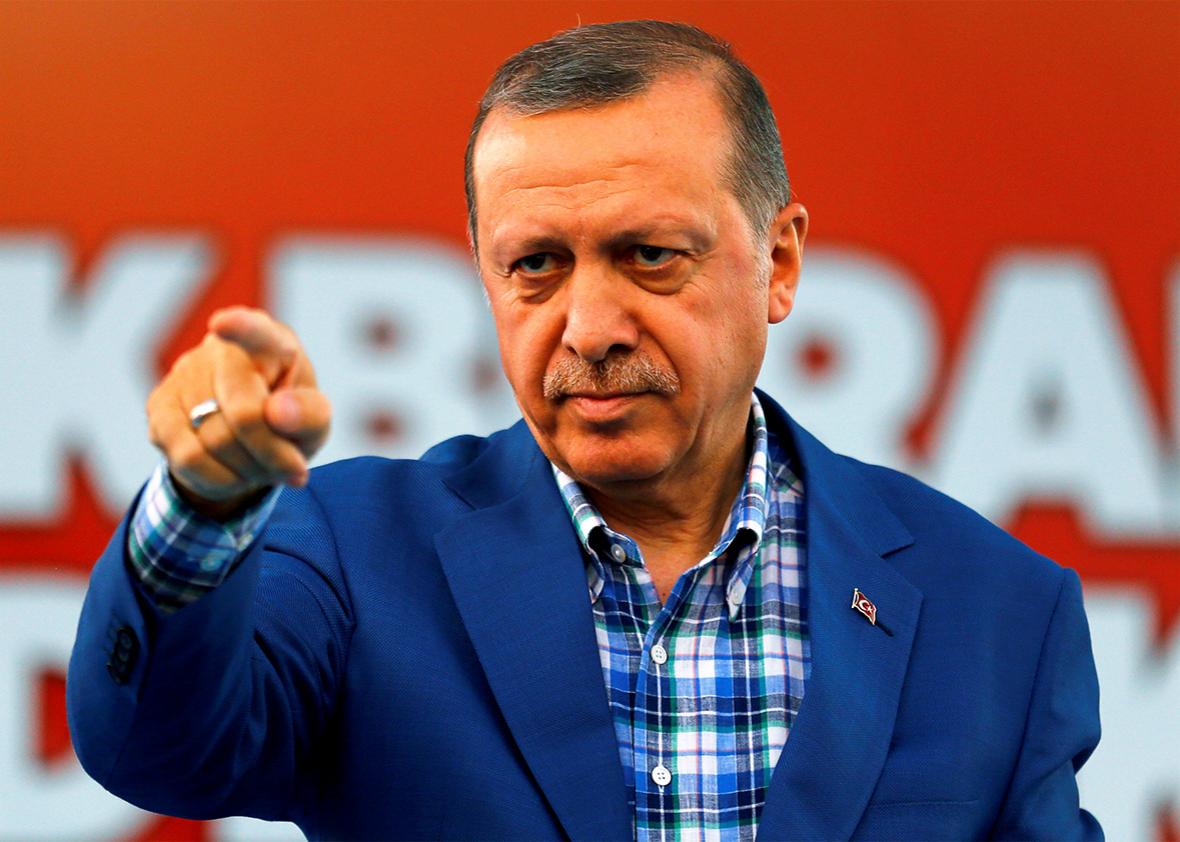

In what will likely rank among the less fruitful sideshows of the G-20 summit in China this weekend, President Obama will meet one on one with his Turkish counterpart, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and discuss recent tensions—to put it mildly—between their two governments.

As if the conflicts in the Middle East weren’t baroque enough, Erdogan’s armored incursion into northern Syria on Aug. 25 smacked the region with a new sheen of complex futility. Some have tried to paint his move as an encouraging sign of Erdogan’s willingness to attack ISIS, as Obama and others have been urging him to do for some time. But several close observers on the ground, civilian and military, say the Turkish offensive was aimed mainly at the Syrian Democratic Forces, a U.S.-backed alliance of Kurdish and Arab militias that is fighting ISIS itself. In other words, the offensive was aimed mainly at Erdogan’s primal enemy—the Kurds—and also at their chief protector, and his new whipping boy, the United States.

Erdogan, according to these sources, seems genuinely convinced that the attempted coup against him on July 15 was hatched by the émigré cleric Fethullah Gülen, who now lives in the Poconos mountains of Pennsylvania—and that Gülen was aided or abetted in this plot by senior U.S. officials, as evidenced by their refusal to extradite him to Turkish soil (a move that would amount to his death sentence).

Vice President Joseph Biden recently flew to Turkey—the first visit by a senior U.S. official since the coup—to assure Erdogan of America’s continued friendship as a NATO ally. Erdogan rewarded the gesture by sending troops and tanks into northern Syria, with no advance notice, while Biden sat at his side. Though the offensive did push some ISIS troops out of their havens, it dealt much more damage to the Arab-Kurdish forces, who have received the most U.S. military aid and have proved to be the most effective force in the ground fight against ISIS. In response, Biden lightly criticized the Turks and sternly demanded that the Kurds pull their forces back across the Euphrates River—a tongue-lashing that puzzled and alienated the Arab-Kurdish alliance, which U.S. Special Forces had been assisting up till then.

At this point, any sane reader might be wondering what the hell kind of war this is and what the hell we’re doing in it. Obama perceived the region’s madness early on: It fueled his reluctance to intervene. And now that he has waded into the dunes, it’s bogging him down. Like the Hotel California, the modern Middle East is “programmed to receive / You can check out any time you like / but you can never leave.”

Though justifiably keen to disentangle himself and his country from the region’s ancient feuds, and instead “pivot” toward the Asia-Pacific’s thriving dynamism (the main agenda of this weekend’s G-20 summit), Obama was pulled back into the land of old morasses by the rise of ISIS and the need to crush the new jihadi movement in its cradle. His idea was to avoid George W. Bush’s approach—a massive invasion by American troops—and instead rely on local Arab and Kurdish forces to fight ISIS on the ground, while the United States provided air support, intelligence, and maybe some arms shipments to a particularly reliable militia. It seemed logical: Every country and almost every militia in the region loathed ISIS. What Obama underrated was just how much those countries and militias (including, very much so, Turkey and the Kurds) loathed one another—to the point that an effective coalition against ISIS proved impossible.

Here is the key fact to understanding the Middle East’s conflicts and why they seem so intractable: The United States is the only combatant in the region that views ISIS as the main threat and that views the destruction of ISIS as the main mission. All of the other combatants regard ISIS as, at worst, a secondary threat; their main threats—real dangers to their regimes and their survival—stem from the long-simmering sectarian rivalries (mainly Sunni versus Shiite) and territorial disputes (leftovers from the arbitrary borders set by European colonialists at the end of World War I), and have little to do with ISIS, al-Qaida, or any other jihadi group. (ISIS exploits these rivalries and disputes, but it doesn’t displace them as primal facts of life in the region.)

As a result, the local powers play the United States, promising or pretending to join the fight against ISIS (and sometimes actually doing so, to some degree) as long as we help them go after their main threats—in other words, as long as we help them pursue their vital interests. But the problem is that the interests of some of these countries conflict with the interests of others. We can’t help all of them without also alienating all of them. And so we wind up wreaking displeasure and worse, no matter what we do.

Kayhan Ozer/Presidential Palace/Handout/Reuters

For a while, Obama tried to transcend these medieval squabbles. After all, the Sunni-Shiite schism had no parallel in U.S. foreign policy. We were friendly with some Shiites (Iraq) and adversarial with others (Iran, Hezbollah, several Iraqi militias); the same was true of Sunnis (friends with Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, the Gulf states—abject enemies with al-Qaida and ISIS). Obama was determined to pursue American interests in the region, regardless of how they fell into local categories. And if these factions—Shiites, Sunni Arabs, and Kurds—could be corralled into an anti-ISIS coalition, if they could cooperate in the pursuit of this common interest, then maybe they could tone down their disputes on other issues. And who better to lead them down this path than the United States, which had relationships with powers on all sides?

Well, it didn’t work. The United States, it turned out, has enough leverage in the region to make the factions diddle us for our support but not enough leverage to impose a single direction. This is another reason for the persistent, multidimensional violence: the absence of an outside international order. For 500 years, the region was ruled by the Ottoman Empire. When that empire collapsed during World War I, the British and French redrew the map of the Middle East and imposed their own surrogates, in part to suppress sectarian self-rule. When their colonial banners receded in the wake of World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union—the emergent Cold War superpowers—carved the world, including the Middle East, into separate spheres of influence. When the Soviet Union imploded and the Cold War ended, it was inevitable that the spheres, the surrogates, and the artificial borders would melt too, reviving the long-suppressed but unforgotten rivalries.

These rivalries—a localized version of the Great Game that lured Britain, France, Russia, Turkey, and other 19th-century powers to compete for treasure and territory in the Middle East and South Asia—dominate everything about the region today. Other outside powers, notably Russia, are getting sucked into this game, and, if the United States remains interested in what happens there, it—we—will get sucked into it too.

From this perspective, it’s clear that other nations are fervently pursuing their interests in the region. Syria’s Bashar al-Assad is fighting for his survival. The mullahs of Tehran are supporting Assad in order to maintain their control of a seamless swath of land from Iran to Iraq to Syria to Lebanon. Russia’s Vladimir Putin is supporting Assad in order to protect his only ally and military base outside the former Soviet Union. The Saudis, Egyptians, and Gulf states are supporting every entity that can halt the onslaught of Iran and its allies. The Kurds want autonomy, preferably across a swath of land covering northern Syria and Iraq. The Turks, worried that progress toward this autonomy might inspire their own Kurds to foment a secessionist uprising and civil war, will do anything to suppress the Kurds, especially if they seem to be getting too strong.

Meanwhile, the Americans want to defeat ISIS, know that they need the local powers to do so, and therefore try to play mediator—a sort of sectarian marriage counselor—for all of the powers’ leaders, who could accomplish so much if only they got their act together. Mediators and marriage counselors don’t last long; they try to settle a fight that took place last week, but the bickering parties see it as an excuse to bring up a disastrous vacation that took place back in 1977 (or, in the case of the Sunnis and Shiites, a convulsive religious schism that took place in the 7th century). America tries to walk down the middle of the road—and gets hit by traffic from both directions.

The mediating approach was working for a while with the Turks and the Kurds. American diplomats and officers would tell the Turks, “We know you hate the Syrian Kurds, but they exist. Who would you rather have as their best friend—Russia, Iran, or your NATO ally, the United States of America? Let us talk to them for you. We can take the edge out of their worst instincts.” At the same time, they’d tell the Kurds, “Moderate your ambitions, don’t throw your successes in the Turks’ face, let us talk to them for you, we can keep them from bombing you.”

Before the attempted coup, this American campaign had persuaded enough Kurdish commanders in Syria, and enough general officers in Turkey, to soften the conflict. Things seemed almost promising. Then came the coup attempt. The Turkish generals who’d worked most closely with Americans were among the hundreds of generals that Erdogan sacked or executed. Since then, Erdogan’s paranoia has deepened on all fronts, and he has fanned anti-American sentiment—in his own speeches and through state-owned media—to unprecedented depths. Even a program as apolitical as the Fulbright teaching fellowship has pulled out of Turkey for reasons of safety. The director of the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Middle East program fled after Turkish media accused him, preposterously, of helping to plot the coup.

Which leads to Obama’s meeting with Erdogan this weekend. Obama has several goals for this session. He needs to convince Erdogan that the United States is—and regards Turkey as—a strong ally. His success or failure at this sales pitch has broad, long-term implications for NATO’s southern front. It also has immediate implications: The air base at Incirlik, which Erdogan shut down briefly in the wake of the coup, is vital for the continuing air offensive against ISIS. At the same time, Obama wants to persuade Erdogan to start pounding ISIS more than he’s pounding the Kurds. And he has to make clear that the United States is not going to extradite Fethullah Gülen without firm proof that the exiled cleric played a role in the coup from his lair in the Poconos—and Obama has to make this clear without sending Erdogan into fits.

But that’s just this weekend. At some point, some American president—it’s too late for Obama—needs to figure out just what the U.S. interests in the regional fight are and how its outcome should look. If the goal is simply to defeat ISIS, without much care for which side comes out ahead in the Sunni-Shiite-Kurdish rift, then that argues for one set of actions. If the goal is to defeat ISIS and prevent the rise of some other, equally savage jihadi group that appeals to Sunnis fearful of Iranian expansion, then that argues for another set of actions.

Obama hasn’t figured out this problem, has barely addressed it. Nor have either of his aspiring successors. There’s a reason for this: It’s hard. It might require taking sides in a regionwide conflict. If it’s deemed a bad idea to take sides, then it may be time to reassess our whole presence in the Middle East. Either way, it requires exercising leverage to bring Russia and other outside powers into the process—and it’s not as if Obama and Secretary of State John Kerry haven’t tried to do this.

Even if an American president—Obama or his successor—spelled out concrete interests, a coherent strategy, and a clear vision of a reasonable outcome to the region’s conflicts and crises, it’s not at all clear if this would make any difference. The region’s governments and factions may be too fundamentally divided to reach a settlement; the outside powers certainly lack the strength and will to impose and enforce one. It may take years, decades, even a century or longer to sort out. This weekend’s meeting between just two of the players, who have enough converging and colliding interests to fill a month of summits, cannot be expected to accomplish much.