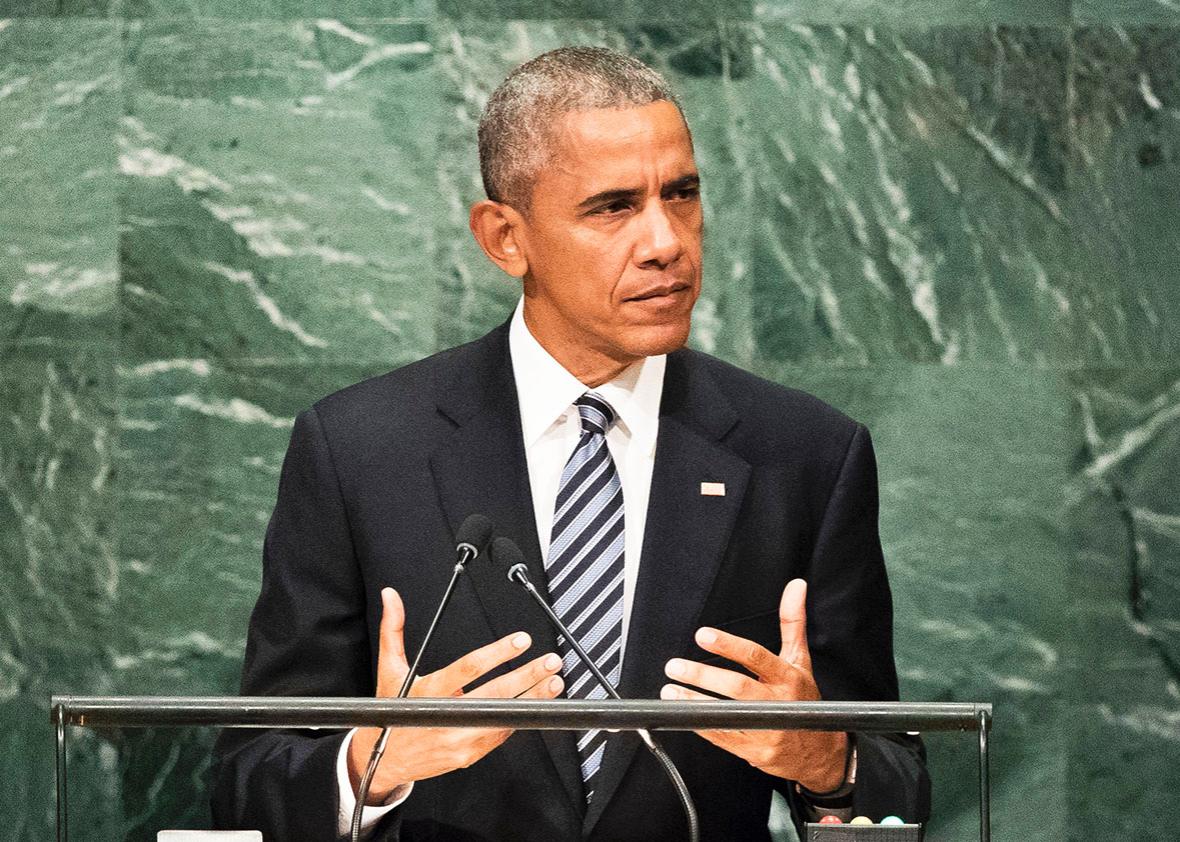

President Obama’s final address to the U.N. General Assembly stands as one of his best speeches on world politics, an analysis as sophisticated as his 2009 Nobel Peace Prize address on the limits and necessity of military force in the post–Cold War age of fractured power.

The speech was full of idealistic passages—he called for more empathy; less strife; and the need for “all of us,” as he said, quoting Martin Luther King, to be “co-workers with God.” But the central theme and deep importance of this speech lay in his pragmatic understanding that the most hopeful and most dreadful trends of the past quarter-century stem from the same source.

This global integration, Obama noted, has improved life for billions of people: The incidence of extreme poverty has declined from 50 percent of the population to just 10 percent; the internet has placed the totality of human knowledge in the hands of anyone with access to a computer or smartphone; the collapse of colonialism and Communism has doubled the number of democracies, allowing millions more people to choose their own leaders. Yet at the same time, the rapid economic growth has deepened inequalities (as most of the growth is concentrated at the top); and although this phenomenon is nothing new, the spread of information has enabled those at the bottom to see the contrast between their own lives and the lives of the better-off—a fact that raises expectations at a rate “faster than government can deliver.” And as government proves ill-equipped to deal with these demands, alternative views of order come to the fore: “fundamentalism, tribalism, aggressive nationalism, and crude populism.”

Historians have long recognized this dynamic. Crane Brinton, in his 1938 The Anatomy of Revolution, dubbed it “the revolution of rising expectations.” But it has eluded most news consumers (who often wonder why people whose lives have lately improved are suddenly rebelling) and, even more so, politicians (who would rather not untangle the complexities, or suffer the sacrifices, of a fix).

This is what makes Obama’s speech so unusual and bold. One implication of his analysis is that peace comes from not simply expanding wealth (which, though that helps, would also exacerbate the internal contrasts) but also spreading it—“not to punish wealth,” Obama emphasized, “but to prevent repeated crises that can destroy it,” since a society “that asks less of oligarchs than [of] ordinary citizens will rot from within.” The same is true of the gap between rich and poor countries, a gap that, he said, the rich countries must do more to close. He acknowledged that foreign assistance is politically difficult, but, again, he presented the urgency not as a matter of charity but of pragmatic self-interest. (Obama has always been more a realist than many of his admirers and critics recognize.)

As with his Nobel address, Obama did not fall back on the bromides that puff most speeches of this sort. There are, he allowed, “no easy answers.” Though global integration inevitably spawns a “collision of cultures,” he called on his fellow world leaders to reject fundamentalism and racism, to embrace a pride in ethnic identity that doesn’t involve sectarian domination, and to experiment with free markets and civil society (instead of indulging the former without the latter—and, yes, he was talking to you, China).

He allowed that “history tells a different story” from the one that he hopes prevails—“a much darker and more cynical view of history,” in which humans are “motivated by greed and by power,” big countries push smaller ones around, and tribes or nation-states define themselves not just by the ideas that bind them but, perhaps more, “by what they hate.” Many times in history, he said, humans think they’ve arrived at an age of enlightenment, “only to repeat cycles of conflict and suffering.” He then said, “Perhaps that’s our fate.”

But, he went on, “the choices of individual human beings,” which led to world wars, also led to the United Nations, which was created to prevent such wars. “Each of us as leaders, each nation, can choose to reject those who appeal to our worst impulses and embrace those who appeal to our best,” Obama said. “For we have shown that we can choose a better history.”

Obama didn’t ignore the choice of a better or worse history facing the citizens of his own country—which is to say, he did take a couple of swipes at Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump, though not by name. At one point, he said, “The world is too small for us simply to be able to build a wall and prevent it from affecting our own societies.” At another: “A community ringed by walls will imprison only itself.”

In that sense, he seemed to be saying, the choices facing the United States have much in common with the choices facing the world, and while the problems are vexing and their politics are difficult, the consequences of making the wrong choice—or not even recognizing the nature of the choices—can be catastrophic.