What a grotesque debate, a travesty of rhetoric, a carnival of buncombe the likes of which even H.L. Mencken (who coined the last phrase) could not have imagined.

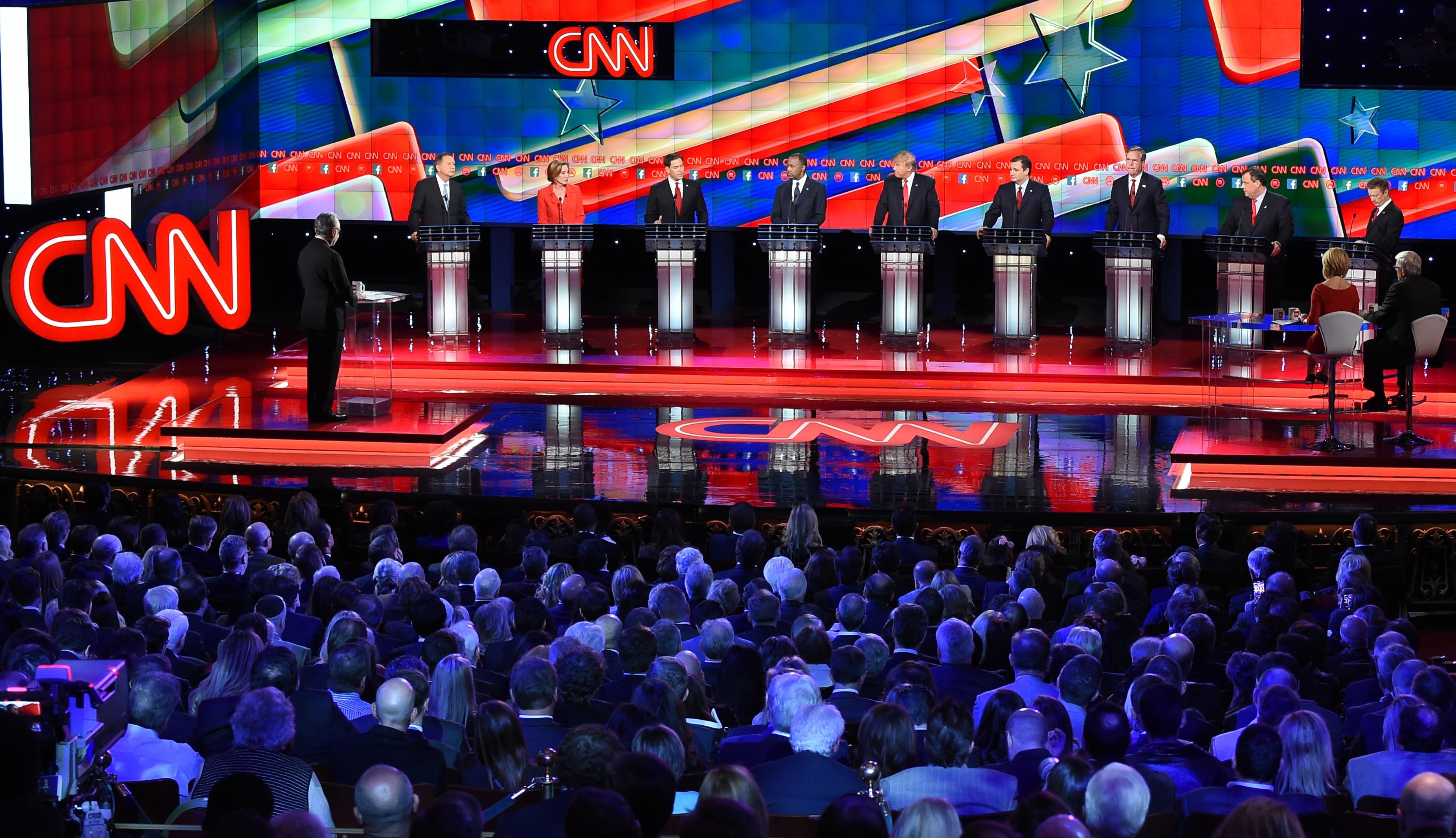

I refer, of course, to Tuesday night’s Republican presidential debate, its entire two hours devoted to national security and terrorism, about which most of the nine major candidates proved they knew nothing, a fact that some tried to conceal by making stuff up.

Donald Trump, the front-runner, was asked to elaborate on his proposal to shut down the Internet to keep ISIS from recruiting on social media. First, he affirmed that this was still his position, saying, “I don’t want them using our Internet” (as if the Internet has a nationality), then added that he was “not talking about closing the Internet,” just “those parts” of the Internet in Iran and Syria (as if each country occupied a sector, some digital latitude and longitude, of the World Wide Web).

Sen. Ted Cruz, who seems to have signed a nonaggression pact with Trump, was asked about his hair-raising proposal to “carpet-bomb ISIS to oblivion.” Did this mean, CNN’s Wolf Blitzer asked, that he’d kill thousands of civilians in towns like Raqqa, Syria? Cruz explained that he would “carpet-bomb where ISIS troops are, not a city”—ignoring (not knowing?) that ISIS formations mainly are in cities. They don’t hang around campfires at night in the desert, forming nifty targets for bombers flying above.

Cruz also outlined his plan for defeating ISIS. “My strategy is simple,” he said. “We win, they lose.” How would he translate this bold idea into action? “We will utterly destroy them by targeting the bad guys.”

Why didn’t Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton think of that?

To judge from the statements of all nine Republicans, you would think that Obama cowers under his desk, afraid to fling an insult at a terrorist, much less drop a bomb. New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, who once hugged Obama for bringing him federal aid in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, now called the commander in chief a “feckless weakling.” Cruz and Ben Carson blamed this weakness on an excess of “political correctness,” citing his refusal to identify the enemy as “radical Islamic terrorists”—as if uttering those three words while dropping 9,000 bombs on ISIS targets would have made a bigger impact on the war than dropping 9,000 bombs (as U.S. war planes have done).

The criticism of Obama, a standard feature of these get-togethers, has ratcheted to a new level. Apparently, he has done nothing to promote national security and everything to set it back decades. Jeb Bush accused Obama of failing to leave a few thousand troops in Iraq (when, in fact, the status of forces agreement signed by Bush’s brother required the complete withdrawal of all troops by the end of 2011). Christie said, puzzlingly, that Obama’s nuclear deal sired the creation of ISIS.

One thing was clear from this debate. None of these nine candidates had any remotely plausible ideas on how to defeat ISIS, or prevent terrorist attacks on American soil, beyond what Obama is already doing—except doing it louder, or with a scarier scowl, or maybe doing more of it.

There was a potentially interesting colloquy between Sens. Cruz and Marco Rubio about the tension between privacy and surveillance—specifically, the USA Freedom Act, the reform bill that ended the National Security Agency’s collection and storage of telephone “metadata,” the files that track the frequency and duration (but not the contents) of phone calls between one number and another. Rubio, who voted against the bill, said it robbed the NSA of a vital tool in tracking terrorists. Cruz, who voted for it, said the bill added new measures that enlarged the agency’s toolbox. The old metadata program, he said, tracked landline calls; the new one would track those of cellphones.

Both claims are false. Cruz is wrong that the bill added new surveillance measures. The NSA had always retrieved metadata of cellphone calls (at times, only cellphone calls). Rubio is wrong that the reform bill—which merely transfers the files back to the phone companies (which created them) and requires the NSA to request them through a secret court—is a huge intelligence loss. He failed to note (maybe he doesn’t know) that the idea for this reform came from Gen. Keith Alexander, then-director of the NSA, who publicly testified—and privately assured many officials—that the slight delay in gaining access to these records would have no impact on counterterrorism. He also admitted that the metadata program hadn’t been very successful at tracking down terrorists in any case. (Other surveillance programs, which the USA Freedom Act did not alter, have been effective.)

You might think that Carly Fiorina, former denizen of Silicon Valley, would know this topic cold. If so, you would be wrong. She said that digital technology has moved on, and so have the terrorists, but that the “bureaucracy” hasn’t. Intelligence agencies need the private sector to help them intercept new communications, but Obama and Clinton never asked for help.

In truth, the NSA and other intelligence agencies have been quite adept at keeping up with the new technologies. To the extent they haven’t (for instance, with Apple’s new encryption programs, which block even Apple from cracking codes), the Obama administration has reached out to Silicon Valley for assistance on a regular basis—to no avail. It’s unclear why these executives would cooperate with Fiorina.

The candidates’ follies and contradictions didn’t end there.

Christie kept citing his work as a federal prosecutor, bringing terrorists to justice in the wake of 9/11. He nabbed them back then, he’ll nab them as president. But did he mean to suggest that ISIS is a law-enforcement problem or that its fighters should be processed through criminal courts? Doubtful, but if he didn’t, why does he think his experience has relevance?

Gov. John Kasich, who’s been relatively moderate when it comes to sending thousands of troops to the Middle East or getting stuck in the middle of the region’s civil wars, suddenly bellowed that America has to go into the war against ISIS “massively, just as in the first Gulf War.” A half-million troops pushed Saddam Hussein’s troops out of Kuwait in that war. Is that what he’s really calling for?

Fiorina’s plan to win the war: “Bring back the warrior class”—by which she means Gens. David Petraeus, Jack Keane, and Stanley McChrystal, who were all “retired early because they told Obama things he didn’t want to hear.” First, Keane retired during the Bush administration. McChrystal had to go because he insulted NATO allies—with whom he was supposed to be forming a coalition in Afghanistan—in the presence of a Rolling Stone reporter. Petraeus—well, we all know what happened there. Does Fiorina really think there are no other warriors among the U.S. Army’s generals?

Cruz said, twice, “Iran has declared war on us,” which must come as a surprise to parties all round.

There were a few sensible moments. Bush railed at Trump’s idea to keep all Muslims out of the United States, noting that we need moderate Muslims to help fight ISIS—that the Kurds and other allies against ISIS are Muslims (something that many Americans might not grasp). Sen. Rand Paul said that another Trump idea—to kill not just terrorists but their families—would require pulling out of the Geneva Conventions and would also sire enormous backlash. Paul also made the valid point that it was infeasible to go to war with ISIS and simultaneously demand Syrian president Bashar al-Assad’s ouster because, horrible as Assad is, his removal would create a vacuum that ISIS would fill. (In his only logical comment of the night, Trump said the same thing.)

But Trump had the last word. “Our country doesn’t win anymore,” he said in his closing statement. “Nothing works in our country. If I’m elected president, we will win again. We will win a lot. We will have a great, great country.”

What the hell is he talking about?