The Iran nuclear talks are about to be declared a success or a failure. Tuesday is the deadline for the negotiators to sign a deal. Officials on the various sides will play up each step toward resolution as a monumental triumph and each step backward as catastrophic. TV newscasts, eager for scoops and drama, will hype these hopes and qualms. Here is a guide on how to watch and interpret the theatrics:

First, if the Tuesday deadline passes without a deal, that means nothing. (Update, June 29, 2015: This scenario is looking ever more likely.) Ever since Iran and the P5+1 nations (the five formal nuclear powers—the United States, Great Britain, France, Russia, China—plus Germany) signed their historic interim accord in November 2013, they’ve extended deadlines twice, to good effect, and they’re likely to extend this one, too. This is how all negotiations work: No country (or labor union, corporation, or whatever entity) surrenders its final bargaining points, or keeps trying to eke concessions from the other side, until it absolutely has to.

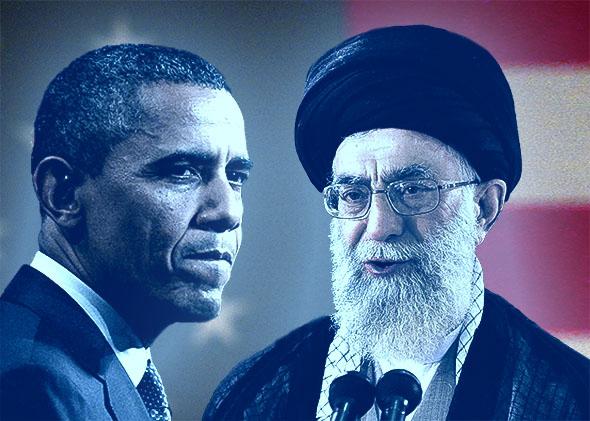

Second, if one side walks out or glumly tells reporters that things look bad, that might mean something—but probably not. At one point during the previous negotiations, in late March and early April, a European delegate flew home, reports circulated that the talks had collapsed, some speculated that Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif had agreed to the West’s terms but that Iran’s supreme leader, the Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, had not. And then, all of a sudden, the negotiators emerged with a framework of an agreement that was far more detailed and restrictive than anyone had predicted.

The negotiators in Vienna are now trying to fill in the blanks and resolve the ambiguities of that framework before—or not too long after—Tuesday.*

It is, even now, not entirely clear what happened in the final hours of the talks this past spring. Did one or both sides change positions on an issue? Were the gloomy press briefings tactical ploys to ply last-minute concessions—and, if so, were concessions made? Either way, this sort of skirmishing has taken place near the end of almost every high-profile arms-control negotiation.

That doesn’t mean it’s all a charade or that all endings have been happy. Sometimes talks have collapsed because the two sides have been unable to close the deal; the distance between their bottom-line positions has been too far. The classic case is the Reykjavík summit of 1986, when, to the alarm of his aides, President Ronald Reagan nearly struck a deal with Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev to dismantle both nations’ nuclear weapons. The deal collapsed when Reagan refused to cancel his “Star Wars” missile defense program. (However, the following year, the two leaders embarked on a series of drastic arms-reduction treaties that helped pave the way for the end of the Cold War.)

Third, American reporters, waiting in Vienna for something to happen, will solicit experts and members of Congress for their views of the situation. Two things to keep in mind: The experts will know nothing about what’s going on behind closed doors; the members of Congress, besides knowing nothing, will have little say on what happens afterward.

The deal being negotiated is not a treaty, which would require ratification by two-thirds of the Senate. Rather, it’s a nonbinding international arrangement to be signed by six sovereign nations. Similar arrangements have been struck on many arms-control measures over the years, including President George W. Bush’s Proliferation Security Initiative; President Gerald Ford’s Helsinki Final Act; and hundreds of bilateral and multilateral measures, guidelines, and memoranda of understanding over the decades.

In other words, Congress has no legal or constitutional role in drafting, approving, or modifying this deal.

However, once certain legislators (of both parties) realized this, they passed a law giving Congress 30 days to review the deal and vote it up or down. Of course, President Obama would veto a nay vote, requiring a two-thirds majority of Congress to override the veto. It’s unlikely that so many legislators would vote down an accord of this sort, but the bill’s sponsors added a twist that gives them slightly better odds: If the negotiations go beyond the Tuesday deadline, and if the president doesn’t send them the text of the deal until sometime between July 10 and Sept. 7, the 30-day congressional review period will stretch to 60 days. Ostensibly this is to account for the August recess, but it would also give opponents more time to muster a case against the deal.

Congress put this extension in the law to put pressure on Obama to get a deal that its critics might find more palatable, but in fact, it may have the opposite effect. To the extent Obama feels pressured at all, this bill might push him to take a fast deal—to wrap things up if not by Tuesday, then at least before July 10, so that the deal’s critics have only 30 days, not 60, to rally the votes against it. Certainly the Iranians realize this; as a result, they may put off their final concessions, thinking that Obama has a greater incentive to rush. In other words, in their power grab, the congressional critics have, if anything, removed some of the American negotiators’ leverage in the talks. If the critics truly fear that Obama might agree to a less-than-good deal, they have pushed him to do so.

Fourth and finally, what’s in this deal anyway, and what are the disputes left on the table? Amid all the commentary about the political horse race, Obama’s legacy, the impact on the 2016 election, and the rest, this question will probably get the lightest media treatment.

The deal was outlined in the April 2 framework, and, viewed as a goal, it’s unassailable. The Iranians stop enriching uranium, cut their stockpile of enriched uranium by 97 percent, reduce their gas centrifuges (the spinning paddles that enrich uranium) by two-thirds, remove all “advanced centrifuges” (which can enrich uranium must faster than the old ones), destroy the core of their heavy-water reactor at Arak (thus preventing the development of a plutonium bomb), and ship all the fuel from that reactor outside of the country. The Iranians also allow international inspectors to verify compliance with the deal far more intrusively than permitted in any previous arms-control accord. Finally, these restrictions will stay in place for at least 10 years, some for as long as 25 years. The upshot is that Iran will be unable to develop an atomic bomb for at least a decade.

In exchange, a wide range of economic sanctions—imposed on Iran by the United States and the European Union—will be suspended (though other sanctions, having to do with Iran’s support of terrorism and its ballistic-missile program, will stay in place).

On its face, this is an extraordinarily good deal, and anyone who says otherwise either hasn’t read the text or simply doesn’t want a deal with Iran of any sort.

However, there are legitimate qualms about the blanks that the final draft of this deal will have to fill in, and here is where close scrutiny is vital. The main issues: How intrusive can the international inspectors be? And exactly when are the sanctions removed?

Some U.S. officials have said that the deal will, or must, let inspectors go “anywhere, anytime,” to make sure Iran isn’t enriching uranium in a covert facility. By contrast, the Ayatollah Khamenei has said he will not allow any deal that lets foreigners run free on Iran’s military bases. Is this an irreconcilable conflict? Maybe, maybe not.

Verification has always been a sore point in arms-control talks. The Soviet-American arms treaties, in Cold War times, never called for “on-site inspections,” because neither side wanted to give the other side such direct access to its sites. As everyone understands, there’s a fine line between inspections and espionage, especially when the signatories are still adversaries (and even when they’re not). The fact that Iran is allowing inspectors to roam its declared nuclear sites—that it’s allowing inspectors on Iranian soil at all—is remarkable, given the history between the two nations.

But what if inspectors suspect that some building is harboring a uranium-enrichment plant? How would a formal deal distinguish between inspections based on reasonable suspicions (derived from satellite imagery, communications intercepts, and so forth) and fishing expeditions for general intelligence? It’s a difficult issue; Khamenei’s concerns are hardly baseless or deceptive. There are ways to write such language into an international treaty or arrangement: procedures and protocols for requesting an inspection, empowering an international agency to rule on such requests. A key to this deal is to keep Iran from cheating—to make the deal palatable without having to rely on simple trust. The challenge is to draft language that both sides find acceptable and effective.

Still more critical, though, is the issue of how and when sanctions are lifted. The rules for verification make up the deal’s enforcement clause; the timetable for sanctions relief lies at the deal’s very center. Khamenei has said sanctions must be lifted upon the deal’s signature. The P5+1 negotiators insist that sanctions stay in place until Iran fulfills most of its obligations—reducing the enriched uranium, dismantling centrifuges, and so forth.

When this issue arose in April, some officials suggested a possible compromise: Upon signature of the deal, the U.N. Security Council would pass a resolution calling for the lifting of sanctions—but the sanctions wouldn’t actually be lifted until Iran fulfills its obligation. Again, this is an issue where the detailed language of the deal will be critical—and no one knows what language might be acceptable and effective, until both sides say it is.

Most of the controversies over the Iran nuclear deal are the stuff of deception or ignorance, but these two are potential deal-killers. If Iran sticks to its hard-core position on either one of them, there will be no deal; if a compromise can be found that finesses the political concerns while addressing the substantive ones, then there will be a deal—and it will be a very good one.

Correction, June 27, 2015: The article originally misstated the location of the talks. Negotiations are taking place in Vienna. (Return to the corrected sentence.)