Drones had been out of the news for a while, until one of them killed Warren Weinstein, an American aid worker held hostage by four al-Qaida fighters in Pakistan. The jihadis were the targets, and they died too, after a careful intelligence analysis that preceded the strike—not careful enough, though, to have spotted Weinstein and a fellow hostage, Giovanni Lo Porto, in the same compound.

There’s a reason for the recent dearth of news about drone strikes: There are far fewer of them now. The Obama administration has launched just five drone strikes in Pakistan so far this year, compared with 22 last year, and down dramatically from a peak of 110 in 2010. A similar trend can be seen in Yemen: nine strikes this year, down from a peak of 47 in 2012.

President Obama placed restrictions on drone strikes two years ago, in a legal document dangling such wide loopholes that, if read literally, it didn’t impose restrictions at all. Lately, it seems, he’s been following the guidelines in their ostensibly intended spirit.

Even so, drones carry such risks and limitations that, after intelligence analysts confirmed the deaths of Weinstein and Lo Porto, Obama felt compelled to deliver a sorrowful speech, expressing “grief and condolences,” profound regret, and “deepest apologies.” He also noted that “this operation was fully consistent with the guidelines under which we conduct counterterrorism in the region”—and therein lies the problem.

In an April 24 Slate column, my friend and colleague William Saletan argued, “For civilians, drones are the safest form of war in modern history … more discriminating and more accurate” than artillery shelling or conventional airstrikes. He’s right, as far as he goes. Since 2004, according to a range of estimates, by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and the New America Foundation, U.S. drone strikes have killed between 2,227 and 3,949 people in Pakistan—between 8 and 24 percent of them civilians. Those are horrifying figures. But by comparison, two-thirds of combat deaths in World War II were civilian, three-quarters in the Korean War, and more than half (probably far more) in Vietnam. Saletan doesn’t mention this, but the Red Cross estimates that, in bombardment campaigns throughout the 20th century, 10 civilians were killed for every combatant casualty.

Photo by Joel Saget/AFP/Getty Images

However, on another level, these comparisons are misleading to the point of meaninglessness. Those 20th-century wars were all-out wars, most of them declared, none of them covert, all of them fought on territory that the residents knew were war zones. An ethical debate could still be held, decades later, on the morality (and strategic wisdom) of bombing cities and villages, even in the context of total war. But drone strikes in Pakistan or Yemen are different in kind: The United States is not at war with those countries.

Imagine that a Canadian general or prime minister launched an airstrike on a border town in Minnesota because some avowed enemies of the Great White North had taken refuge there and that, as a result of bad aim or poor intelligence or dumb luck, a few—much less a few dozen or a few hundred—Americans were killed. The American people and the U.S. government would be outraged. If we didn’t already hate Canadians, we would start hating them then, maybe even start killing them in return.

So it is with Yemen, Pakistan, and many parts of Afghanistan, where Americans continue to drop bombs from the sky.

This is no dovish viewpoint. Retired Gen. Stanley McChrystal, who ordered a lot of drone strikes when he was chief of special operations in Iraq and commander of NATO forces in Afghanistan, said, in a Reuters interview not long after hanging up his uniform, “The resentment created by American use of unmanned strikes … is much greater than the average American appreciates. They are hated on a visceral level, even by people who’ve never seen one or seen the effects of one.”

There is another disturbing aspect of these drone strikes. The original purpose of these weapons was to kill high-level al-Qaida commandos who were holed up, or constantly on the move, and could not be killed or captured in any other way. However, something happened over the years: Commanders and presidents came to see the drone as an attractive alternative to combat. President Obama found them especially alluring. He was eager to get out of Iraq, keen to step up the fight in Afghanistan without sending in too many more troops, and leery of terrorists plotting attacks on the homeland from craggly mountains and caves throughout the CentCom region. What better device than a drone—a pilotless airplane, armed with a camera and extremely small, accurate bombs, steered by joystick-pilots inside air-conditioned trailers halfway around the globe—to neutralize dangers with no sacrifice of American lives?

The drone made war all too easy. It indulged us (and I mean all of us) in the illusion that we could kill bad guys without fighting a war at all. (Only the people in the drones’ shadows thought that we were at war with them.) Gradually, the CIA came up with the concept of “signature strikes.” The officers planning the strikes didn’t have to know a target’s name or rank; they had only to observe certain things about his behavior—as picked up by drone cameras, satellites, cellphone intercepts, spies on the ground, or other sources and methods—that strongly suggested he was an active member of an organization whose leaders would be the natural targets of a drone strike. He might be moving in and out of a known terrorist compound or training at a known terrorist facility: In other words, his behavior bore the “signature” of a legitimate target.

Drone strikes over Iraq and Afghanistan were (and, in the case of Afghanistan, still are) commanded by the military; much of the information about them is public. But the strikes over places like Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, and Sudan—nations with which we are not officially at war—are run by the CIA and are, by nature, covert operations. Everything about them is highly classified, so we don’t know how many of these operations are aimed at specific individuals and how many are aimed at behavioral types. But a senior American official told me two years ago that the “vast majority” of drone strikes in Pakistan were signature strikes.

The calculation is less arbitrary than it might seem. Over the years, intelligence officers have become quite good at reading these signatures; they usually get it right. In an otherwise critical article in the Atlantic, David Rohde, the journalist who was held hostage by jihadis for several months, wrote that his captors were terrified of drones, which they said had killed several senior commandos, including one who’d been teaching them how to build roadside bombs.

But quite often, even when the drone crews read the signatures correctly, the militants they kill are low-level fighters, far from the “high-value targets” for which the drones—and their vast infrastructures—were intended. Killing them has no effect on the battlefield or on the broader “war on terror,” not even in theory.

And then sometimes the crews get the signatures all wrong, with calamitous consequences. In the opening chapter of his book Kill Chain: The Rise of the High-Tech Assassins, Andrew Cockburn paints a horrifying scene of two SUVs and a pickup truck, driving along a road in Afghanistan, crammed with 30 men, women, and children, being mistaken as jihadis because of their “signatures”—driving fast, in what looked like a caravan, just a few miles from U.S. troops (a tragic coincidence, as it turned out), at one point getting out of their cars to pray (which one “trained” U.S. officer took as prelude to an attack)—and thus falling victim to a drone strike. (Cockburn quotes the conversations between the pilots and their supervisors, transcribed in an official Air Force inquiry, which found the crews “unprofessional” and “out to employ weapons, no matter what.”)

Some criticize drone warfare as cowardly: remote-control killing, from half a world away, without the slightest risk of death in return. In a sense, this is off the mark. People, usually those on the losing end of battle, said the same thing about the inventions of the longbow, the artillery shell, the missile, and the aerial bomber. It’s natural for warriors to maximize the damage done to the enemy while minimizing the risk to themselves. In a sense, the drone is the latest phase in this evolution.

But in another sense, the drone is something different. Never before have warriors been able to remove themselves entirely from the battlefield. The crews in the intercontinental ballistic missile silos could do that, too; but the point of their presence was to deter nuclear war, to make it extremely unlikely they’d ever have to turn the launch key, and if they did, that would be one of the last things they ever did, because the Russians would fire their ICBMs right back. By contrast, drone operators watch the gray, fuzzy video feeds all day, in 12-hour shifts. They are in the thick of battle as much as anyone on the ground; they feed intelligence to the troops and sometimes they kill the enemy with the same lethality as a sniper on a nearby roof. Yet, the setting is pristine and abstract. At the end of the day, they drive home to their spouses, companions, or pets, have dinner, watch TV, and go to sleep in their own beds.

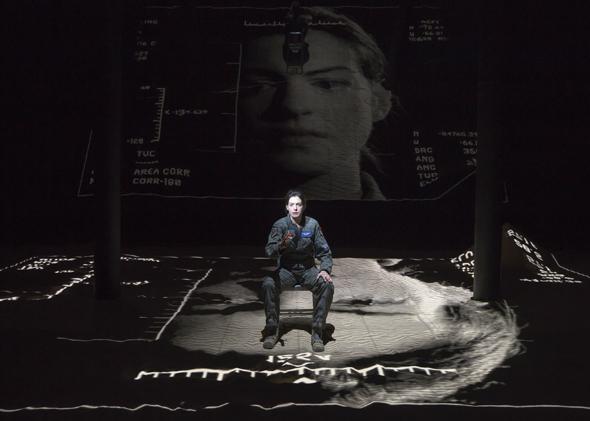

Photo by Joan Marcus/Public Theater

A new one-woman play, Grounded, by George Brant—now at New York’s Public Theater in a dazzling production directed by Julie Taymor—captures some of the weird dissonance of a drone pilot’s life. The Odyssey “would be a different book,” she muses at one point, “if Odysseus came home every day, every single day.”

The pilot (played by a convincing, even riveting Anne Hathaway) was once a real pilot, an F-16 fighter jock, psyched on “the speed … the ride … the respect … the danger” of hurling through the sky (“You are the blue”), raining missiles down on the desert, breaking minarets into particles of sand. Now she drives to war, “like it’s shift work,” and stares at a gray screen, watches the “silent gray boom” after she pushes a button, and hovers over the scene long after, watching the body parts fly, then the mourning and anguish of those who retrieve them—sights that she had never stayed around to witness before. She begins to see gray everywhere, melding her life that’s not quite a life with her combat that’s not quite combat, imagining the Nevada desert of her daily drive as the Iraqi desert of her daily surveillance, blurring a jihadi’s daughter that she’s killed with her own daughter, and gradually she goes haywire.

Brant’s play is reminiscent of, and must have been to some degree inspired by, Matthew Power’s 2013 article in GQ, “Confessions of a Drone Warrior,” in which his subject, Airman 1st Class Brandon Bryant, recounts the “zombie mode” and “fugue state” of his shifts in the joystick trailer, watching and killing from so near, yet so far: the dissonance of the godlike power and the gray silence.

Photo by Joan Marcus/Public Theater

In 2011, when drone strikes hit their peak, an Air Force psychologist surveyed 840 drone operators and found nearly half of them suffering from high stress. A subsequent study revealed that drone operators experience the same levels of PTSD, alcohol abuse, and suicidal tendencies as traditional combat pilots.

Yet this is the future of air war. In 2009, for the first time, the Air Force trained more drone pilots than cockpit pilots, and soon after elite cadets—those who, a few years earlier, would have been steered to the latest fighter jets—were encouraged to fly Predators, Reapers, or Global Hawks, to name a few of the most prominent unmanned aerial vehicles.

Today, the armed forces of 78 nations have surveillance drones, nine have armed drones, and another nine are developing armed drones. Just four nations—the United States, Great Britain, Israel, and Pakistan—have fired munitions from drones in wartime. American drones ride high and unchallenged in the skies, both for surveillance and for shooting—but this is likely to change. The change will be a long time coming: Drones are easy to build, but the satellites, communications links, and imaging technology—the things that give American drones their range, precision, and supremacy—are hard. But hard isn’t impossible, and a long time isn’t forever. No weapon in history has arrived without provoking a matching or countervailing weapon. The drone is unlikely to be an exception. And then the real blowback might begin.

Grounded ends with the burnt-out pilot addressing the audience: “One day it will be your turn, your child’s turn, and yeah, though you mark each and every door with blood, none of the guilty will be spared.” As drama, it’s overwrought; but as prediction, there’s something to it.