The U.S. Central Command’s Twitter and YouTube accounts were hacked Monday by someone peddling ISIS propaganda. The proper response is a shrug.

Hackers try to launch assaults on Defense Department computers and networks hundreds of times a day. Sometimes they succeed; once in a while, the breach is serious. This one is not.

Matthew Devost, president and CEO of FusionX LLC, one of the top cybersecurity firms, calls the intrusion “embarrassing” but “harmless.” Central Command—which oversees U.S. military operations in the Middle East and South Asia, including airstrikes against ISIS in Iraq and Syria—pulled its social media accounts offline to prevent further embarrassment.

The hacking might be a matter of concern if Centcom’s Twitter and YouTube accounts were somehow linked to its more operational servers. But this is extremely unlikely. Ordinary people don’t link their Twitter or Facebook pages to, say, their bank accounts or credit card numbers; if they do, they’re idiots. Some military commands could be more careful in their wanderings through cyberspace, but they’re not idiots.

The Web comic XKCD puts the hack into perspective. The first frame of a recent strip shows a TV newscaster saying, “Hackers briefly took down the website of the CIA yesterday.” The second frame reads, “What people hear: Someone hacked into the computers of the CIA!!” The third frame reads, “What computer experts hear: Someone tore down a poster hung up by the CIA!!”

That’s the long and short of Monday’s hack: Someone tore down a poster hung up by Centcom.

It’s a fair bet, nonetheless, that the head of Centcom, Gen. Lloyd Austin III, is chewing someone’s head off. Having a Twitter feed hacked is no big deal, but it indicates that someone was careless with a password or fell for a phishing expedition (i.e., clicked on an email attachment that installed malware); and if doing that exposed Twitter and YouTube to a cyberattack, someone else higher up might get careless with the passwords for a more substantive site.

Classified servers have rarely been hacked by adversaries, at least as far as officials know. (Who knows whether, or how often, they’ve been hacked without detection? The answer is, by nature, unknowable.) But the military runs many “sensitive but unclassified” sites that, if hacked, could reveal vital information about military operations—a particular unit’s travel and logistics plans, the workings of a computer-controlled electrical power grid, the phone numbers and addresses of key officers, and so forth.

In 1998, after President Clinton ordered a Navy vessel to fire cruise missiles at al-Qaida training camps in Afghanistan, a Pentagon official in charge of cybersecurity (an obscure issue back then) went online to see how quickly he could identify and locate the wife and children of the officer who fired the missiles. It took less than an hour; the officer had listed their names and hometown in a biographical sheet on the Navy’s website. If al-Qaida terrorists had been cyber-smart back then, they could have done the same thing. About this same time, the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the National Security Agency ran an exercise to test the vulnerability of the military’s command-control networks; it turned out they were horrifically vulnerable.

In the decade and a half since then, the Pentagon and the military commands have stepped up cybersecurity as a matter of top importance, installed intrusion detection systems, created specialized offices and protocols, and issued frequent, almost continuous updates to keep networks secure.

But the militaries of at least two dozen nations now have sophisticated cyber-units, with specialties in offense and defense, and a cyber-arms race has spiraled into several cycles of escalation—a new cycle every few months, as an assault generates a patch, which spurs a maneuver around the patch, which generates yet another patch. As these cycles have spun out, the line between cyberdefense and cyberoffense has blurred, with many countries (including the United States) adopting a strategy of “active defense”—penetrating other countries’ computer networks to see what kind of attacks they’re gearing up. Of course, this approach can be seen (and intended) as an enhanced form of cyberdefense or as battlefield preparation for a future cyberoffensive.

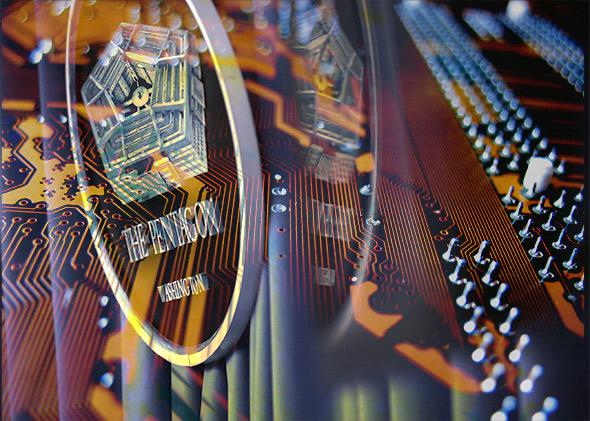

Cyberwar, cybersecurity, cyberespionage, cybercrime—these are real and widespread activities, often indistinguishable in appearance and technique. The entire realm has evolved into not merely a wilderness of mirrors but a thicket of funhouse mirrors, some of them refracting or distorting, others deeply hidden, even invisible. It’s a theater of confusion, even to the small number of officials with the special security clearances that put them in the know—and utterly bewildering to the rest of us, who are affected by its wreckage.

The subject needs to be opened up to wider discussion, not in all its details but certainly in its basic concepts and premises. Meanwhile, one thing is clear: The hacking of Centcom’s public website is a harmless nuisance, a distraction from the real set of issues revolving around both cybersecurity and ISIS.