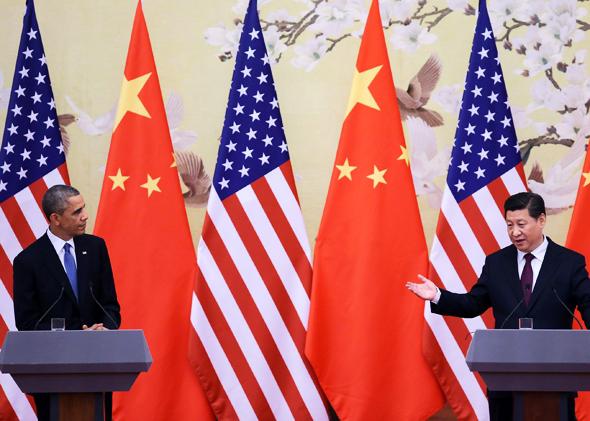

So much for the notion that his party’s reversals in the midterm elections would diminish President Obama’s standing at this week’s summit in Beijing. Far from viewing the American leader as a “political casualty” (as the New York Times predicted), Chinese President Xi Jinping met with him privately for more than four hours and signed a slew of unprecedented bilateral accords, including pledges to limit greenhouse gases, reduce tariffs on American high-tech products, and set safety protocols on military exercises.

None of this is to say that China has softened its regional ambitions or that U.S.-Chinese relations have struck a chord of pure harmony or even that these agreements—signed Wednesday, at the summit’s conclusion—will end global warming, revitalize the U.S. economy, or transform the South China Sea into a zone of peace and stability.

But they will prod things in that direction. More to the point, they suggest that Xi is coming to see that with great power comes at least some responsibility, and that his country lacks the economic vitality and military strength to achieve that power, or exercise that responsibility, on its own—that he still needs to make deals with the West, especially the United States.

The deals aren’t breathtaking, nor should anyone expect them to be. The accord on carbon dioxide emissions is a case in point. China is pledging that its emissions will peak by the year 2030, and that by that time, renewable sources of energy—such as wind and solar—would grow to 20 percent of total output.

At first glance, this isn’t so impressive, and in this case, the first glance is right. A 2011 study by the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory concluded that, due to natural processes—slowing population growth, the winding down of urbanization, and the consequent saturation in construction and ownership of electrical appliances—China’s CO2 emissions “will peak around 2030.” In other words, even without this accord, the socioeconomic-demographic trends would level off Chinese emissions around the same time.

But that doesn’t mean the accord should be dismissed as trivial. The Lawrence Berkeley study’s conclusions also assume that China stays on track in its planned conversions to solar and wind power. (Those sources can’t grow to 20 percent of a country’s energy output overnight.) And so, the treaty commits the country to stay on that not-so-easy course of change.

Finally, until now, China has resisted pressures to commit to some quantitative target or specific timetable in reducing CO2 emissions. It’s significant that Xi conceded that point. And now that China has done so, the West should push him to level off emissions by 2025 or even earlier.

“They realize they’re being shamed, and that’s important to them as a growing power,” says Elizabeth Economy, director of China studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. The Ebola epidemic is another case in point. As the disease spread and many nations sent aid to afflicted African countries, China initially did nothing, until everyone started pointing fingers, noting the shameful contrast between China’s vast economic investments in Africa and its failure to help the continent’s most distraught people—at which point it donated quite a lot.

The agreement to reduce tariffs on high-tech American products is also significant. Xi had hoped that China would have built its own information-technology industries by now; his cybersleuths have stolen enough blueprints for the design of microchips and related gear. But it hasn’t happened, so to boost China’s economy, he has to open up trade with the outside world, even if it helps the latter as much as it helps China, if not more so. That’s what free markets are about.

Yet Economy cautions that Xi has not changed his view of U.S-Chinese relations as fundamentally competitive or his ambition to spread China’s influence (and diminish America’s influence) throughout Asia. In an article in the latest issue of Foreign Affairs, titled “China’s Imperial President,” she writes of the “implicit fear” in Xi’s vision: “that an open door to Western political and economic ideas will undermine the power of the Chinese state.”

Hence Xi’s crackdown on all dissent, his thorough censorship of the Internet (Freedom House ranks China 58th out of 60 countries on Internet freedom), and his self-aggrandizement of all state power. (He heads the Communist Party, the Central Military Commission, and various groups in charge of the economy, military reform, and national security.)

That also explains Xi’s attempts to lure all Asian nations to an Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, with the idea of cutting them off from Western financial institutions. As Xi put it at a conference in May, “It is for the people of Asia to run the affairs of Asia, solve the problems of Asia, and uphold the security of Asia.”

So far, the Asian nations aren’t lining up to join, nor have they tossed out their collection of Western business cards.

China is emerging as a powerhouse, but that doesn’t mean it has the power to assert itself without contest. For 40 years, China hawks have been warning of an impending Chinese “blue-water navy” and “power-projecting air force.” Now it has one aircraft carrier, and it’s displayed a stealth fighter jet, once on a runway during a visit by then-Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and once in a photo of the plane flying, during this week’s summit. In both cases, it was the sort of teeth-baring growl in which real global powers don’t need to indulge.

Besides, as Economy notes in her Foreign Affairs article, some of Xi’s actions, at home and abroad, are working against his long-term ambitions. His political crackdowns are alienating the sort of technically talented young people he needs to recruit. His tentative economic reforms are stifling growth. And his “winner-take-all mentality,” as reflected in the often-gratuitous naval confrontations, “has undermined his effort to become a global leader”—a mismatch he’s tried to realign in this week’s summit.

In short, it would be a mistake to ignore or downplay Xi’s challenges and ambitions, but it is a bigger error still—because it would play into his hands—to exaggerate his strength and scoff at his diplomacy as mere ploys.

Before and during the summit, President Obama has handled China with a mix of diplomacy and containment, pushing all doors that might lead to cooperation while firmly engaging all pressure to compete—for instance, sending Marines to Australia, reinforcing air and naval bases in Japan, deploying ships and planes to the South China Sea, and backing up allies (especially Japan, South Korea, and Vietnam) in resisting China’s aggressive claims along maritime borders.

Even several of Obama’s critics, including U.S. military officers who specialize in Asian affairs, regard his balancing act as shrewd and effective.

As long as they don’t make matters worse, or distract from necessary defensive measures, or turn American policymakers all rosy-eyed, all diplomatic forums with China—all accords to clean the environment, open free trade, and help keep eyeball-to-eyeball military exercises from spiraling out of control—are good things. Anyone in Congress who stands in the way of any of these measures is doing a disservice to U.S. interests, regional stability, and the long-term aim of containing China’s disturbing tendencies while promoting its assimilation into the global economy.