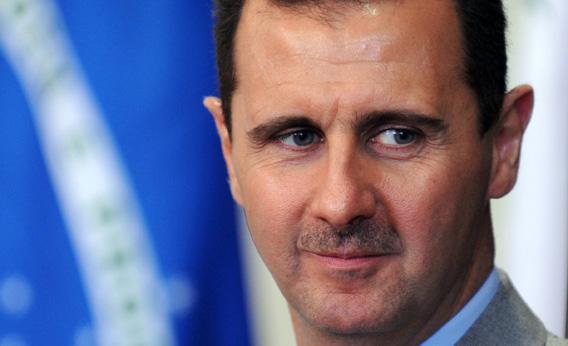

President Obama has warned the Syrian government that any use of chemical weapons in its ongoing civil war would “cross a red line.” Two questions come to mind: What will Obama (and other world leaders) do if the line is crossed? And given that Syrian president Bashar Assad has already killed more than 40,000 of his own people through more conventional methods, what’s the big deal about chemicals? Why should they trigger alarms that his heinous acts to date have not?

NBC News reported this week that Syrian military officers have loaded the precursor agents for sarin, a particularly lethal nerve gas, into bombs that could be dropped from dozens of combat aircraft. Syria has stockpiled roughly 500 tons of the stuff; anyone exposed to a mere one-tenth of a gram would likely die. In short, if Assad wanted, he could turn whole cities into wastelands.

That is one reason why chemical weapons, especially these chemical weapons, are viewed as something qualitatively different. It’s why they are designated “weapons of mass destruction” (even if they’re less destructive than their biological or nuclear cousins) and why 188 nations signed the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention Treaty, outlawing their use, production, or stockpiling. (Syria is one of just six nations not to sign the treaty, the others being Angola, Egypt, North Korea, Somalia, and South Sudan.)

So a bright red line separates chemical weapons from conventional munitions for moral, humanitarian, and legal reasons. Not just Obama but the leaders of the other signatory nations have an obligation to respond in some very serious fashion if Assad crosses the line—to send the clear message, to everyone, that the use of these weapons is completely unacceptable.

But Obama’s warning is also driven by classical realpolitik—the hardcore logic of national-security interests. The leader of any militarily powerful nation is certain to abhor, even to fear, chemical weapons because they tend to level the playing field. In a crisis or conflict, they don’t tilt the balance of power in favor of a much smaller regime, but they do make it harder to coerce, threaten, or topple it. They’re even more potent, in this sense, than a small nuclear arsenal because nuclear facilities—reactors, missiles, launch-control centers, and so forth—are elaborate and usually fixed; they can be identified, targeted, and attacked. This is much less true of nerve gas.

Another alarming aspect of chemical weapons: They’re not even weapons in a strictly military sense. They’re instruments of sheer mayhem, useful only to terrorists, crazy men, or desperate tyrants grasping to stay in power.

Several armies tried to use gas as a weapon during World War I, especially on the Western Front. But horrible as they were, they did little to break through the stalemate of trench warfare, especially once gas masks were introduced. Sometimes shifting winds blew them back toward the attackers. (Nerve gases, such as sarin and VX, are more lethal than the mustard gas of WWI, but protective suits have been designed against them, too.) This is a major reason why so many nations signed the treaty to ban chemical weapons; they’re not very effective weapons. Iran and Iraq used them against each other in their long war of the 1980s, but to no great advantage. In 1988, Saddam Hussein used them on Kurdish rebels, most notoriously in the village of Halabja, killing 5,000 people in a single day. But again, this was a terrorist attack; gas is an efficient tool for killing lots of unprotected, unarmed people.

Which is why many leaders—not just Obama—are worried about the sarin-filled bombs being loaded onto the planes of the Syrian air force. Assad has already killed so many of his own people, who’s to say he won’t kill many more? Hence Obama’s threat about the “red line.” But what does it mean? What is Obama threatening to do if Assad crosses the line?

During the 1991 Gulf War, Saddam Hussein possessed chemical munitions, which he could have loaded into Scud missiles and fired into Israel. Knowing this, James Baker, President George H.W. Bush’s secretary of state, publicly stated that any chemical attack on Israel would be treated in the same way as a nuclear attack on the United States. Saddam must have taken this seriously: He fired many Scuds into Israel during that war, but none of them were tipped with chemical munitions.

Obama hasn’t gone as far as Baker, and it wouldn’t be a good idea to do so, given that he and other world leaders are trying to pressure Iran—one of Syria’s main allies—into halting its own nuclear-weapons program. Nor would it make much sense to attack Syria’s chemical stockpiles: First, their locations aren’t all known; second, blowing them up could scatter the gas for miles around, killing hundreds or thousands of innocent people.

One clear option might be to attack Assad himself or his aides and hideouts (assuming we can track them). There are other, more indirect measures as well, and no doubt some of them are being discussed in the meetings that Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has been holding with top Russian diplomats. The Russians are Assad’s ultimate protectors, yet they are—and always have been—extremely nervous, more so than many U.S. administrations, about letting even the closest allies lay their hands on weapons of mass destruction. Any pressure from Moscow—either the threat of an attack or the act of withholding aid and supplies—could have more effect than anything we could do. (This is another good reason for not turning off that “reset” button in U.S.-Russian relations.)

The bigger concern is what happens with all this sarin after Assad falls or during the civil war’s final convulsive stage (if the Russians can’t persuade Assad to avoid such a dramatic collapse by going into some pre-arranged exile). U.S. experts are reportedly in Syria, instructing rebel officers on how to secure chemical sites—a smart idea, but it can only go so far. A Pentagon official once estimated it would take 75,000 U.S. troops to secure those Syrian sites; even allowing for exaggeration, this can’t be done easily. And some of those rebels we’re training may be foreign agents or jihadists themselves.

And so, there are actually several red lines here. Some of them, we don’t even know about; for many of those, neither we nor any one power can do much to punish the transgressors.