Robert Caro’s series on The Years of Lyndon Johnson, now in its fourth volume (with, the author’s health willing, one more to go) ranks among the towering achievements in literary biography. Volume 1, The Path to Power, tracing the future president’s youth, may be the best book ever written about the role of money in American politics. Volume 2, Means of Ascent, while deeply flawed, is a seminal study in corruption. Volume 3, Master of the Senate, is a riveting portrait of how LBJ transformed a deliberately sluggish institution into a vehicle for self-aggrandizement and social justice.

But Volume 4, The Passage to Power—covering the 1960 election, LBJ’s forlorn vice presidential years, the assassination of John F. Kennedy, and Johnson’s ascension and first actions as president—is something else.

On the good side (which is considerable), and like all the others, it is a terrific read. Caro paints palpable scenes and draws vivid characters. His account of why Kennedy picked LBJ as his running mate is compelling, as is his case that, had JFK lived, he probably would have dropped Johnson from the ticket in ’64. His detailed description of how Johnson manipulated the Senate to pass a tax cut and the Civil Rights Act—bills that JFK had sent up but would never have pushed through on his own (because he didn’t understand the Senate the way LBJ did)—is gripping.

But two things make this book less essential than the others. First, unlike the other volumes, the era it treads is hardly unpaved territory. One of Caro’s major themes—the hatred between Johnson and Robert Kennedy—was the topic of Jeff Shesol’s 1997 Mutual Contempt: Lyndon Johnson, Robert Kennedy, and the Feud that Defined a Decade. The once-secret tape recordings, which serve as Caro’s source for LBJ’s wheeling and dealing in his first months as president, were transcribed and annotated by Michael Beschloss in Taking Charge: The Johnson White House Tapes, 1963-64. Caro writes up this material with more verve and unfurls new details, but, for reasons beyond his control, Vol. 4 doesn’t provide a whole new look at an era the way his earlier volumes did.

But my second problem is much more serious: Caro’s treatment of the 1962 Cuban missile crisis—and of the roles that Johnson and the Kennedy brothers (especially Robert Kennedy) played in the crisis—is, on several levels, simply wrong.

I find it unsettling to write that sentence. After all, this is Robert Caro we’re talking about: the investigative historian with the gnawing need to hunt down every source and unearth every detail of a story before committing it to type, the man who has often proclaimed, as his credo in research, “Turn every page!”

And yet, when it came to the defining episode of JFK’s presidency, a pivotal moment in Cold War history, the closest that the United States and the Soviet Union ever came to nuclear war, Caro left many pages—whole documents—unturned, unread, unopened. Either that, or (a more troubling and, my guess is, less likely possibility) he chopped and twisted the record to make it fit his narrative.

This point is not a disagreement about interpretation; it is a statement of fact. Like Johnson and Nixon after him, John F. Kennedy surreptitiously recorded conversations of historic consequence—including the 13 days in October 1962 when his top advisers, assembled as the Executive Committee of the National Security Council (or ExComm), discussed what to do about the nuclear missiles that the Soviets were erecting 90 miles off the coast of Florida. These tapes have long since been declassified and publicly released, so we know exactly who said what at those sessions. And these hard facts are, in crucial ways, different from the story that Caro (along with, to be fair, many other historians) tells.

The crisis began when U.S. spy planes detected Soviet ships carrying missiles to Cuba, as well as the construction of missile-launchers at secured sites on the island. At first, JFK and his advisers figured they’d have to bomb the missile sites—until they calculated the complexities and risks, at which point Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara suggested a naval blockade of the island as a way to buy time and give Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev a chance to reverse course. After 13 days of shrewd diplomacy, a deal was struck, and the missiles were withdrawn.

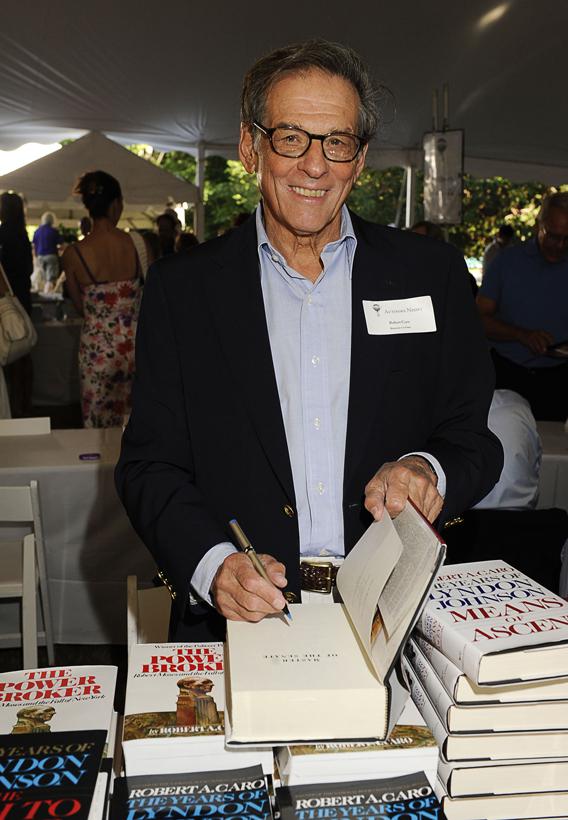

Eugene Gologursky/Getty Images.

In the 50 years since, the story and the lessons of the crisis have gone through a fascinating evolution.* In the first phase, as reported by JFK’s favored columnists (and formalized in the books by palace guards, speechwriter Ted Sorensen’s Kennedy and White House gadfly Arthur Schlesinger’s A Thousand Days), JFK won the confrontation through sheer threat of force. As one of the advisers was quoted as saying, “We went eyeball to eyeball with the Russians—and they blinked.” (This quote, like much else in these accounts, was pure fiction.)

In the second phase, starting in 1982, on the 20th anniversary of the crisis, some of JFK’s top advisers—McNamara, Sorensen, national security adviser McGeorge Bundy, and others—confessed, in a article for Time magazine, that Kennedy had made a secret deal: Khrushchev would take the Soviet missiles out of Cuba, and Kennedy, six months later, would take America’s very similar Jupiter missiles out of Turkey. It had always been known that Khrushchev offered such a deal, but the earlier accounts—including Sorensen’s book, and many other books based on it—had reported that Kennedy rejected it. In fact, the advisers now said, Kennedy accepted it, but told both the Russians and the handful of his own advisers whom he let in on the secret never to tell anyone. (The advisers decided to break their silence because they knew the Kennedy Library was about to release the tapes.)

The third phase began in 1987, with the release of the first tape transcripts, which revealed that the advisers had omitted one key fact in their now-it-can-be-told article for Time: They had all vociferously opposed the trade. JFK stood alone on making a deal with the Soviets—and, in the end, was redeemed.

For inexplicable reasons, most popular histories of the crisis (and a few academic ones as well) have not incorporated this last revelation. They have neglected, misread, or ignored the evidence that has been out there for the last 25 years.

And now Robert Caro joins that crowd.

In Caro’s account of the crisis, Robert Kennedy, the attorney general and president’s brother—once a mean hawk—took a sensitive, dovish turn when facing the abyss, a turn that, over the next few years, humanized his attitude toward politics more broadly. And, in this account, Lyndon Johnson reveals his hawkishness so blatantly that he lost all favor with President Kennedy.

Caro’s analysis of LBJ’s hawkishness is misleading; his depiction of RFK’s dovishness is untrue.

On RFK’s alleged change of heart, Caro cites two bits of evidence. First, during a discussion about scenarios for bombing the Soviet missile sites, Bobby passed a note to Jack, saying, “I know now how Tojo felt when he was planning Pearl Harbor.” Second, at a session on Oct. 19, just a few days into the crisis, Bobby drops his earlier support for an air raid, saying, “For 175 years, we have not been that kind of a country. A sneak attack is not in our tradition.”

The Tojo note is attributed to Sorensen’s book and, like much else about the crisis in that book, is almost certainly fiction. [Update, June 7, 2012: The note is real. Read the explanation below.] Historians at the JFK Library have avidly searched for that note; they cannot find it. As for the comment about a “sneak attack,” the key word is “sneak.” Robert Kennedy had problems with a sneak attack, not with an attack. Six days after this session, on Oct. 25, he made the distinction explicit, saying that it might be a good idea to warn Soviet personnel at the Cuban site “to get out of that vicinity in 10 minutes, and then we go through and knock [out] the base.”

Caro does not quote this remark.

In fact, at the same Oct. 19 meeting where he spoke up against a “sneak attack,” RFK also said, “It would be better for our children and grandchildren if we decided to face the Soviet threat, stand up to it, and eliminate it, now. The circumstances for doing so at some future time were bound to be more unfavorable, the risks would be greater, the chances of success less good.”*

Caro does not quote this line either—which, by the way, RFK made after the disavowal of a “sneak attack,” meaning that if Bobby’s heart softened with that comment, it hardened again just minutes later.

At another meeting (also missing from Caro’s account), when a Soviet ship seemed about to break through the American naval blockade and some of the president’s aides talked about ordering crews to board the vessel, RFK said, “Rather than have the confrontation at sea, it might be better to knock out the missile bases as the first step.”

On the last day of the crisis, when Khrushchev offered the Cuba-for- Turkey trade, Robert Kennedy argued against the deal. “I don’t see how we can ask the Turks to give up their defense,” he said. “God, don’t bring in Turkey now. We want to settle [Cuba first],” he said later on. JFK sent his trusted brother Bobby to the Soviet ambassador to accept the deal, though not in writing. But even then, he did so reluctantly. Talking casually with McNamara after the ExComm session, as the tape runs out, Bobby says, “I’d like to take Cuba back. That would be nice.”

From start to finish, and on several occasions, RFK can be heard on the tapes, and read in the transcripts, arguing not only for an air attack but for an air strike followed by an invasion of the entire island of Cuba. Sheldon Stern, the library’s former chief historian, who has studied the tapes and transcripts more thoroughly than anyone, writes in his forthcoming book The Cuban Missile Crisis in American Memory: Myth versus Reality: “RFK was one of the most consistently hawkish and confrontational members of the ExComm.”

The same can be said of Lyndon Johnson, who, the few times he did speak up at the ExComm meetings, was (as Caro accurately quotes him) brutally bellicose, calling the president’s patience—his failure to meet Khrushchev’s forceful gestures with immediate force—a sign of “weakness” and “backing down.”

But, except in tone, Johnson was no more hawkish than Bobby Kennedy—and, especially on the last day of the crisis, no more hawkish than nearly all the advisers at the table.

When President Kennedy says he’s disposed to take Khrushchev’s missile trade, McGeorge Bundy, the national security adviser, protests (you can hear his voice on the tape, quivering), “I think we should tell you … the universal assessment of everyone in the government who’s connected with alliance problems: If we appear to be trading the defense of Turkey for the threat in Cuba, we will face a radical decline.”

McNamara, a key moderate, the advocate of the blockade at the start of the crisis, is an all-out hawk by its final days, arguing—in a bit of crazed logic rivaling Dr. Strangelove’s—that we should remove the Jupiter missiles from Turkey but only after we attack the Soviet missiles in Cuba. (For the full, jaw-dropping quote, taken from the official transcript of the session, which Caro seems not to have read, click here.)

Many histories of the crisis, especially those written before the tapes were released, portray the ExComm sessions as a struggle between the hawks and the doves. But by the end of the crisis, there were no hawks and doves; there was only President Kennedy, who favored making the trade with the Russians, and everybody else, who loathed the idea. (Near the end, just one adviser, George Ball, who became the house dissident on the Vietnam War during LBJ’s presidency, sided with the president.)

Bobby Kennedy may have transformed himself later, after his brother was assassinated, but Jack Kennedy emerges as the lone fount of wisdom in the tapes and transcripts.

Caro misses this fact. The day before Khrushchev offered the Cuba-for-Turkey missile trade, he sent the White House a different proposal: He would remove his missiles from Cuba if Kennedy vowed never to invade Castro’s island. When the missile-trade deal came across the line the next day, many of JFK’s advisers—including RFK—suggested that he accept the first letter’s offer and simply ignore the second letter. The books by Sorensen and Schlesinger contend that JFK did precisely that.

Caro, citing those two books (and interviews he conducted with both authors), writes that the president “kept postponing his decision” on whether to take their advice. In fact, he did nothing of the kind. The moment Khrushchev’s second letter came over the wire, JFK said, “To any man at the United Nations, or any other rational man, it will look like a very fair trade.”

Kennedy let his advisers—RFK, McNamara, Bundy, Dean Rusk, and others—rail against the idea for a while, then said, calmly, “Now let’s not kid ourselves. Most people think that if you’re allowed an even trade, you ought to take advantage of it.”

This discussion was taking place on a Saturday morning. The Joint Chiefs had drawn up a plan for striking the missiles—with 500 air sorties—and mounting an invasion the following Monday. JFK mused, “I’m just thinking about what we’re going to have to do in a day or so … 500 sorties … and possibly an invasion, all because we wouldn’t take the missiles out of Turkey. And we all know how quickly everybody’s courage goes when the blood starts to flow, and that’s what’s going to happen in NATO … when we start these things and the Soviets grab Berlin, and everybody’s going to say, ‘Well, this Khrushchev offer was a pretty good proposition.’ ”

Even so, the advisers railed against the idea. Finally, Kennedy sent Bobby to meet with the Soviet ambassador and take the deal.

John Kennedy is the real hero of the Cuban crisis, but Caro misses this because he follows Sorensen and Schlesinger too closely (something he explicitly doesn’t do in other chapters of this book). He even credits Secretary of State Dean Rusk with devising the idea of telling the Soviet ambassador that the United States would remove the Jupiter missiles from Turkey in six months, as long as the deal isn’t publicized. In fact, this was John Kennedy’s idea.

Sorensen and Schlesinger, of course, idolized Jack Kennedy. But given the politics of the early ’60s, JFK wanted to put forth the word that he’d stood up to the Soviets with strength, that he hadn’t made a deal. After a while, they came to believe their own myth.

Caro’s depiction of the crisis fits into the two main strands of his book’s broader narrative: the burning hatred between Johnson and Bobby Kennedy and Johnson’s growing isolation within the Kennedy administration. He writes that, after Johnson’s bellicose display in the ExComm, JFK cut him off even more than before. That may be true, but if it’s because of Johnson’s stance in the crisis, JFK should have distanced himself from Bundy, McNamara, and the others as well.

I would argue (and here we do get into interpretation, even speculation) that JFK did just that. Over the course of his brief presidency, he came to realize that the smart men all around him weren’t as smart as they seemed. The Bay of Pigs taught him not to believe everything the CIA told him. Discussions about the Laos crisis (during which the Army urged an invasion, the Air Force called for air strikes, and the Navy advocated sending in carriers) taught him that the generals were often self-interested. And the Cuban missile crisis taught him that his brain trust of civilian advisers had their shortcomings, too.

One of JFK’s deep failures was not letting LBJ in on this emerging wisdom. Kennedy told only seven of his advisers that he’d taken the missile-trade deal; Johnson was not among them. Maybe he was going to take Johnson off the ticket in ’64 (Caro makes a convincing case on grounds quite apart from the Cuban crisis), but he was murdered before then—and Johnson inherited not the real lessons of the crisis but the tale that Sorensen (ironically, at JFK’s behest) invented.

In his 1988 memoir Danger and Survival, McGeorge Bundy recognized that hushing up the missile trade had pernicious consequences: “We misled our colleagues, our countrymen, our successors, and our allies” into believing “that it had been enough to stand firm on that Saturday”—a false lesson that JFK’s successors applied, with delusional confidence, in Vietnam.

Volume 5 of Caro’s series will deal mainly with Johnson and Vietnam, and I’m afraid that his treatment of the Cuban missile crisis in Volume 4 sets the stage for more false lessons. My suspicion, inferred from what really happened in those ExComm meetings, is that JFK would have pulled out of Vietnam—or at least would not have escalated so deeply. The lesson isn’t that Johnson marked a departure from Kennedy’s men; it’s that, when it came to questions of war and Communism, JFK himself was departing from the views of Kennedy’s men. It would have been good—it might have made a big difference in world history—if Johnson had known that. And, for the life of me, I don’t understand why Robert Caro made the same mistake.

(For more on the sources of the JFK tapes, and other studies of the crisis, some of which Caro used, many of which he didn’t, click here.)

—

The Passage of Power: The Years of Lyndon Johnson by Robert A. Caro. Knopf.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.

Update, June 7, 2012: I need to set the record straight on the longstanding claim that, during the Cuban missile crisis, Robert Kennedy wrote a note to President John Kennedy, saying, “I know now how Tojo felt when he was planning Pearl Harbor.” In the column above, I charged that the claim was “almost certainly fiction,” citing historians at the JFK Library who have searched for this note in vain. Well, my source for this—Sheldon Stern, the library’s former chief historian—turns out to be wrong. RFK did indeed scribble this note to his brother, on Oct. 16, 1962, the first day of the crisis; a facsimile has long been on display at the library’s exhibition on the crisis. (For a view, click here and scroll down to the second-to-last document.)

This mistake does not alter my point, which is that RFK was consistently hawkish during the crisis, not dovish, as Caro contends. Despite this memo, Bobby repeatedly advocated bombing the Soviet missile sites and invading Cuba. His Tojo reference inspired him to oppose only a “sneak” attack; at one point, he suggested giving Khrushchev 10 minutes’ warning before attacking. Still, on the note itself, I am guilty of the same lapse as Caro on the broader points: I should have checked out the claim myself rather than rely on someone else’s recollection. (Return to the updated sentence.)

Corrections, June 1, 2012: This article originally referred to “the 60 years” since the Cuban Missile Crisis. (Return to the corrected sentence.) This article originally misquoted Robert Kennedy saying, “The circumstances for doing so at some future time were bound to be more favorable” when he said circumstances would be more “unfavorable.” (Return to the corrected sentence.)