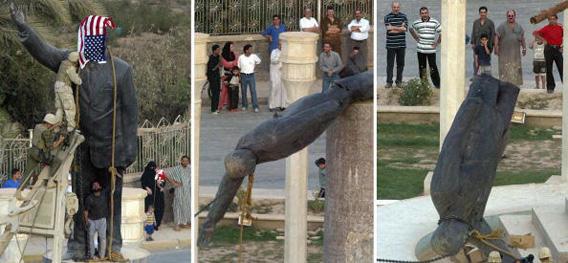

As the last American troops leave Iraq (a remarkable phrase, which many once doubted would ever be uttered), two questions come to mind: Was the war worth it? And did we, in any sense, win?

The two questions, of course, are related: The first concerns cost, the second benefits. But however you do the calculation, it’s clear that the decision to invade Iraq was a major strategic blunder—and that the policies we pursued in the early months of the occupation tipped the blunder into a catastrophe.

If we’d known in March 2003 that Saddam Hussein had neither weapons of mass destruction nor ties with al-Qaida, there is no way Congress would have authorized the war. That the Bush administration roared ahead on little more than a suspicion of these connections—which top officials hyped by cherry-picking raw intelligence and willfully inflating the warning signs from “possible emerging threat” to “clear and present danger”—constitutes an act of historic infamy.

Besides being an unnecessary war, the plunge into Iraq was also a distraction from Afghanistan, at a time when even a few more resources and a little more attention might have put down al-Qaida for good and laid the groundwork for a somewhat stable civil society. In this sense, the last decade of bloodshed in Afghanistan (and across the border in Pakistan) might also have been unnecessary.

The turn to catastrophe came in mid-May, five weeks after U.S. forces rolled into Baghdad and toppled Saddam’s regime, when the imperious L. Paul (“Jerry”) Bremer issued his first two orders as head of the Coalition Provisional Authority. Order No. 1 barred members of the once-ruling Baathist party from holding any but the lowliest of government jobs. Order No. 2 disbanded the Iraqi army.

Suddenly, tens of thousands of Iraqis, most of them young men with weapons (and the knowledge of where to find more), were turned out into the streets, officially disenfranchised and, in many cases, eager to rebel against the agents of their fate. An insurgency arose. There were no Iraqi security forces to clamp it down. Most of the American forces had been trained only to “break things and kill people,” an approach that, applied to this sort of revolt, sired only more—and still angrier—insurgents.

The tragedy is that all this was not just foreseeable but foreseen. Before the invasion, the National Security Council held two principals’ meetings, with President George W. Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney, and all the relevant Cabinet officials present. At one, they agreed unanimously to hold tribunals—similar to the truth commissions in post-Soviet Eastern Europe and post-apartheid South Africa—that would determine which Baathists could stay in their jobs and which couldn’t. At another, they agreed, also unanimously, to preserve the Iraqi army, except for the elite Republican Guards and the most highly ranked officers—and even the latter could appeal for reconsideration. In fact, at the time Bremer issued his orders, teams of U.S. officers were working with the more amenable Iraqi generals to round up and reactivate their old units.

It’s weird that, almost nine years later, we still don’t know who wrote those directives—or why Bush (who learned about them the same way everyone else did, through the newspapers) didn’t reverse them right away. I’ve speculated here before that the lineage runs from Rumsfeld to Cheney and, from there, to the crafty Iraqi exile Ahmad Chalabi. Still, it’s baffling that Rumsfeld in particular—who was so eager to pull out the U.S. troops as soon as possible after Saddam’s ouster—would, at the same time, consent to directives that left Iraq without any means of keeping its people secure. Even his fatuous remark at a press conference, shrugging off the early looting (“Stuff happens … Freedom’s untidy”), doesn’t account for the sheer idiocy of this negligence.

I should acknowledge that I supported the decision to invade Iraq from Feb. 5, 2003, when Secretary of State Colin Powell presented the case for going to war to the U.N. Security Council (a briefing that he later regretted), until March 2 (still two weeks before the war began), when an article by George Packer in the New York Times Magazine reported that President Bush had no idea that Iraq consisted of Sunnis, Shiites, and Kurds, much less that toppling Saddam could uncork sectarian tensions, which could sire civil war. On March 5, I joined the opposition, writing that, “however justified the coming war with Iraq may be, the Bush administration is in no shape—diplomatically, politically, or intellectually—to wage it or at least to settle its aftermath.”

I took, and still take, no satisfaction in being proved right.

That said, Bush changed course dramatically at the end of 2006, and I should also acknowledge that I was wrong in predicting that the shift would make no impact on the course of the war.

Bush’s shift consisted of three decisions that, in fact, proved crucial. He fired Rumsfeld and replaced him with Robert Gates. He gave Gen. David Petraeus a fourth star and put him in command of U.S. forces in Iraq. And he ordered a “surge” of 20,000 extra troops in support of a new counterinsurgency strategy.

It was a “gamble” (as Thomas Ricks characterized the move). Most senior officers, though glad to be rid of Rumsfeld, opposed the surge and were skeptical of the new strategy. Even its advocates, at least the ones I interviewed at the time, thought it had a 10 to 20 percent chance of succeeding. That seemed like slim odds for such a huge risk, and for that reason, I wrote very critically about the doubling-down (as did many others). I admired Petraeus and saw the logic in his strategy, but I thought that it wouldn’t work, that the war was too far gone, that there was no sense spilling more blood for a lost cause.

Yet by the summer of 2007, it was hard to deny that something was happening. Civilian casualties were way down. The Shiite militias had retreated. More and more Sunni militias were cooperating with the same American troops that they’d been trying to kill just a few weeks earlier. And the Iraqi military was gaining in strength and competence.

Much of this stemmed from developments that had little to do with American policies or actions. Many Sunni leaders—beginning in Anbar province, which had been one of Iraq’s most violent sectors—suddenly realized that the foreign jihadists, with whom they’d struck an alliance, formed a bigger threat than the American occupiers, and so they turned to the U.S. troops for help. Around the same time, Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki realized that Muqtada al-Sadr’s Shia militia, with which he’d struck an alliance, was more a threat to his regime than a bulwark, and so he grew gradually less resistant to letting U.S. troops move in and crush them—which spurred Sadr to declare a cease-fire.

Still, it took the presence of Petraeus and his strategy to exploit the “Anbar Awakening” and to coax Sunni leaders throughout Iraq to follow its example. And it took the surge of additional troops to help the co-opted Sunnis secure and hold the territories that they’d wrested back from the jihadists. What resulted was not the whack-a-mole of securing one province, then leaving to secure another, but rather the more enduring measure of holding several provinces all at once.

Petraeus said many times that the point of the surge (by which he meant the surge of troops and ideas) was to give Iraq’s political factions a zone of security—some “breathing space”—so they could focus in peace on hammering out their differences and creating a cohesive, legitimate government.

The American troops fulfilled their part in this bargain, more so than anyone had envisioned. The problem today is the Iraqis. They didn’t take advantage of the breathing space. The main issues that divided the parties (which is to say, the sectarian factions) five years ago continue to divide them today.

There is still no firm agreement on sharing oil wealth. The Kurds and Sunni Arabs still squabble over property rights in Kirkuk. Maliki himself has obstructed efforts to incorporate the Sunni Awakening’s soldiers into the national Iraqi army.

The good news—and this is due, in no small measure, to Bush’s decisions at the end of 2006, as well as the way the Obama administration has managed the transition since 2009—is that there is a functioning Iraqi government. The means and institutions do exist for resolving these problems mainly through politics.

However, the troubling fact is that these differences among the factions are no small matters. They reflect central issues of power, wealth and identity. Failure to resolve the disputes in the halls of politics may spur the most militant constituents—of whom there are many—to revive their armed struggles in the streets.

Whether we “won” the war in Iraq remains an unsettled question. It hinges, at this point, on which way the Iraqis turn.