Last week an Egyptian court dismissed charges against former President Hosni Mubarak, who had been accused of stealing from the state treasury and ordering troops to fire on civilians during mass protests in 2011. The collapse of this trial was the latest failure of a global effort to “end the impunity” of government leaders who order subordinates to engage in human rights abuses. This effort is futile. It’s past time for commentators to understand that “the principle that no person is above the law, especially those at the top,” is a slogan, not a principle, one that can rarely be lived up to because it misdiagnoses the politics of revolution.

Mubarak was the authoritarian leader of Egypt for 30 years. He rigged elections, jailed political opponents, presided over a notoriously brutal security apparatus, censored the press, and banned political rallies. He was tremendously corrupt; he and his family accumulated $1 to $5 billion during his reign.

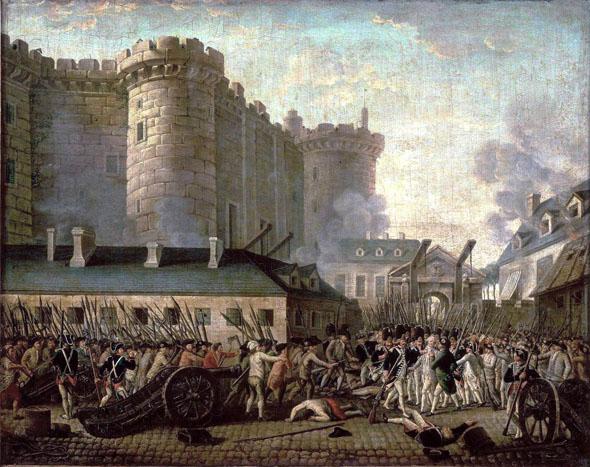

The Economist, from which I quoted above, eagerly anticipated Mubarak’s trial, proclaiming “the urgent need for the open and speedy dispensing of proper justice for all serious offences, Mr. Mubarak’s trial to the fore.” So did many other commentators, as did the revolutionaries themselves. No one seemed to realize how unusual such a trial would be. In all of history, hardly any overthrown leaders have been subject to a trial. If you exclude trials by foreign powers (the Nazi leaders at Nuremberg, the Japanese leaders at Tokyo, former Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic, Saddam Hussein), you have a short list, indeed. Charles I (1649), Louis XVI (1792), and a few others in the past few decades, whose trials have largely been charades, like that of the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu. Most revolutionaries either slaughter their deposed enemies or chase them into exile. When an authoritarian regime makes a peaceful transition to democracy (as is usually the case), the former authoritarian leaders are immunized from prosecution as part of the deal.

There is a reason for this. All dictators maintain power by drawing on the support of vast numbers of people, including the elites. All of those people are complicit in the dictatorship, and so if the dictator is to be tried, then they must be as well. Even if they are not charged immediately, the trial of dictator will implicate them and throw into doubt their security from further prosecution. A country can function only if the bulk of the population—including most of the former dictator’s supporters and the elites who populate the military, bureaucracy, and higher reaches of the economy—cooperates with the new regime. If the new regime can’t make peace with them and immunize them from prosecution, then the only alternative may be civil war or social disintegration.

Thus, the United States found itself unable to prosecute all the Nazis and ultimately used various subterfuges to reintegrate all but the worst into society. In Japan, the United States spared the emperor and numerous war criminals high and low. In most of the peaceful transitions (Spain, Greece, Portugal in the 1970s, Eastern Europe in the 1990s, South Africa), members of the old regime were left alone or subject to minor restrictions. In Iraq, the United States blew it by trying to destroy the entire Baathist establishment. Partly as a consequence, the country lies in ruins.

In Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood—Mubarak’s only real political opposition—came to power in 2012 and was driven from office a year later after popular protests against President Mohamed Morsi spurred the military to stage a coup. Morsi wanted to prosecute Mubarak, but now it’s Morsi’s turn to be in the dock. While Morsi won an election, he was not able to keep the country together for longer than a year.

Morsi alarmed the Egyptian public, especially liberals, because he seemed intent on consolidating power and becoming an authoritarian himself, with the goal (unlike Mubarak) of imposing religious law, Iran-style. Indeed, Mubarak was friendlier to women’s rights and education, and religious tolerance, than Morsi was. And while Egyptians understandably wanted to get rid of Mubarak, by developing-world standards, Mubarak was not a terrible leader.

During Mubarak’s 30-year reign, the Egyptian economy grew at a moderate, healthy rate, thanks in part to reforms implemented in the 1990s. Real gross domestic product per capita (in current U.S. dollars) increased six-fold, from $509 to $2,972. According to data from the World Bank, literacy for adults increased during this period from about 44 percent (in 1986) to 72 percent. (For women, the increase was from 31 percent to 64 percent.) The mortality rate for children younger than 5 fell from 166.1 to 22.8 per 1,000 live births. Life expectancy at birth increased from 58 years to 71 years. The number of women compared with the number of men enrolled in universities increased from 46 percent to 91 percent. The percentage of the population living at $2 per day fell from 28 percent (in 1991) to 15 percent (2008).

During this period, Mubarak faced significant challenges to security. From within, he faced terrorist groups like al-Qaida and the Islamic Jihad, which assassinated his predecessor, Anwar Sadat. Although Mubarak was heavily criticized for the violence he used against his political opponents, he kept his country together and contained Islamic extremism. Compared with Syria and Iraq, where ISIS roams about, beheading, crucifying, and enslaving its enemies, Egypt is a paradise. Under Mubarak, Egypt avoided the civil war that is raging in its neighbor Libya, and the mass killings that took place in another neighbor, Sudan.

Mubarak also conducted a moderate foreign policy. Until Sadat made peace with Israel in 1978, Egypt was at war repeatedly—and not just against Israel. Mubarak resisted pressure to repudiate the peace deal and has not gone to war with a foreign state, except as an ally of the United States against Saddam Hussein in 1990-1991. Instead, Mubarak acted as a mediator between Israel and the Palestinians. In a neighborhood full of bloodthirsty dictators, Mubarak showed considerable restraint.

None of this excuses Mubarak’s corruption, but it helps to explain why the Egyptian revolution’s Thermidor came as quickly as it did. For all its problems, the Egyptian state functioned. Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood overreached by seeking a transformation of society that would have thrown it into permanent turmoil. A trial of Mubarak would have played into their hands. The military and elite in Egypt could not let that happen.