Last week, the Kenyan Parliament enacted a new counterterrorism bill amid scuffles and protests. Opponents argued that, by restricting liberties, the main effect of the bill was to increase presidential power rather than to counter terrorism. The U.S. State Department complained that the bill restricts freedom of speech and freedom of assembly. This bill came on the heels of another government action to deregister hundreds of nongovernmental organizations that had criticized the government.

Kenya’s president, Uhuru Kenyatta, is not (yet) a dictator, but Kenya is less free than it was 10 years ago. And Kenya is not alone. There has been a surge of authoritarianism around the world, reversing decades of progress toward democracy.

Back in 1989, Francis Fukuyama proclaimed “the end of history” with the collapse of communism. Fukuyama meant that the death of communism left liberal democracy as the only legitimate political system. It was only a matter of time before democracy would spread around the world.

While Fukuyama’s theory was based on his reading of Hegel, the German philosopher who believed that history unfolded according to an inherent logic in the direction of freedom, his argument was related to a long-standing debate among political scientists about the relationship between economic growth, or “modernization,” and democracy. Data on these variables showed that while poorer countries cycled between democratic and authoritarian systems, and authoritarian governments in rich countries like Singapore often endured, countries that became wealthy and then established a democracy never seemed to revert to authoritarianism. So democracy seemed to work as a ratchet that would engage if a country achieved a certain level of wealth, and if revolution or reform brought about democratic institutions. Even if Fukuyama (and Hegel) were wrong about the logic of history, there was good reason to believe that, given enough time and economic growth, democracy would spread.

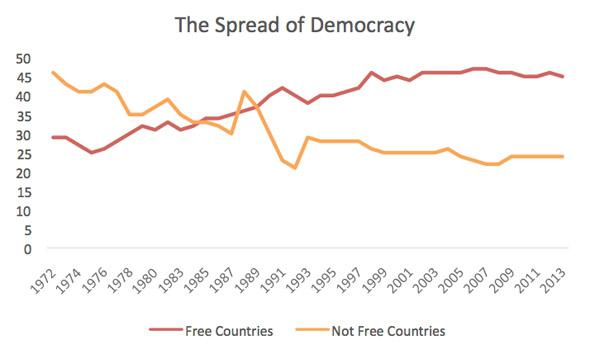

Fukuyama’s argument received a huge amount of attention because it played into the heady sense of victory after the end of the Cold War. But democracy had been spreading since the early 19th century. And while it has endured some ups and downs, the trend is unmistakable. As the accompanying graph shows, since 1972, the fraction of “free countries” has increased from 29 percent to 45 percent. (The source of the data is the think tank Freedom House; for clarity I have omitted countries that Freedom House defines as “partly free.”)

Chart via Freedom House

But the graph also shows that stagnation set in about 10 to 15 years ago. No one knows why. It might be a random fluctuation in an irreversible trend, as Fukuyama’s argument suggests, but it also may indicate that the engine of democracy has run out of steam.

As we look around us, we can see some evidence for the latter interpretation. Probably the most striking examples are the advance of authoritarianism in two relatively wealthy and modern-seeming democracies, Turkey and Hungary. In those countries, a charismatic leader has used his control of the government to crack down on criticism in the media and squelch dissent from political opposition. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has jailed political opponents and harassed the media. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban says he wants to create an illiberal state modeled on Russia and Turkey.

Russia, which lumbered toward democracy in the 1990s, has become an increasingly authoritarian place. Vladimir Putin has skillfully consolidated the power of the government without resorting to communist-era totalitarianism. He has undermined the independence of the media, harassed and stymied his critics, and manipulated elections. While the collapse of oil prices spells trouble for the Russian economy, Putin remains popular. Russians seem to like having a strong leader, even if that means that the media are controlled and political opposition is muted.

China’s authoritarian system is increasingly admired throughout the developing world. The government has managed to maintain order (the country is enviably safe) despite wrenching economic and social change. Since the size of China’s economy surpassed that of the United States earlier this year, it will become increasingly hard to maintain that democracy is necessary to economic development. In many poor countries, where ending soul-crushing poverty takes precedence over Western-style political freedoms, governments have taken note.

Another warning to democrats is the collapse of the Arab Spring. Back in 2010, when the Arab Spring began, it was possible to think that democracy would finally make headway in a region that has long resisted it. It didn’t. President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi’s consolidation of power in Egypt, with the help of liberals who feared Islamic rule by the Muslim Brotherhood, shows vividly that people can prefer the stability of authoritarianism to the chaos of democracy.

A last example is Cuba. Cuba is a full-fledged dictatorship, one that jails and tortures dissidents, muzzles the press, and refuses to hold elections. It is tempting to think that the normalization of relations with Cuba will bring democracy to that country. But that has not happened with Russia, China, and countless other authoritarian countries that the United States trades with. President Raúl Castro has made clear that he plans to maintain Cuba’s authoritarian system while working on economic reform, along the lines of the China model. The cheering from Venezuela and other parts of Latin America expresses the relief felt by leftist authoritarians who see that if the United States can tolerate an undemocratic Cuba, it will have no grounds for criticizing authoritarianism in their countries. This is as it should be. The opening to Cuba is best understood as long-overdue recognition by the United States that economic sanctions can do little to improve political freedoms in foreign countries.

For quite some time, U.S. foreign policy has been based on the assumption that we should promote democracy. Taking countries as they were was regarded as defeatist and un-American. The seemingly relentless rise of democracy made this approach seem reasonable, and perhaps it sometimes was. But much of the flowering of democracy took place in Western countries, or countries that inherited Western institutions and norms from Western colonizers. So advances in democracy that we attributed to our own benevolent influence probably reflected deeper-seated historical and cultural factors over which we have no control. It may well be that democracy has reached its limits. A policy of getting along with our neighbors, rather than forcing them to change for the better, is past due.