President Obama faces his final two years in office with hostile Republican majorities in the House and Senate. So what can he accomplish to secure his legacy as he limps to the finish line? Actually, quite a lot. Bestowed with massive powers by the Constitution and thousands of statutes that delegate authority to the executive branch, Obama could make significant progress on his agenda in three ways.

First, immigration. Obama has already announced that “before the end of the year, we’re going to take whatever lawful actions that I can take, that I believe will improve the functioning of our aliens system.” He is almost certainly referring to a plan to permit millions of illegal immigrants to remain in the country if they are related to people living in the United States legally and have resided here a longish period of time. This plan would extend an earlier action that permitted illegal immigrants to stay and work in the United States if they came here as children, have resided here continuously, and have not committed any serious crimes.

Second, climate change. Regulators under the Obama administration have already moved to cut carbon emissions of power plants and certain vehicles. Obama could extend these regulations to almost any other source of carbon emissions, such as refineries, manufacturers, and airplanes, and make them tougher if he wants. The Obama administration has also indicated that it will negotiate an agreement on carbon limitations with other countries, and abide by that agreement even if the Senate blocks an effort to confirm the agreement as a treaty.

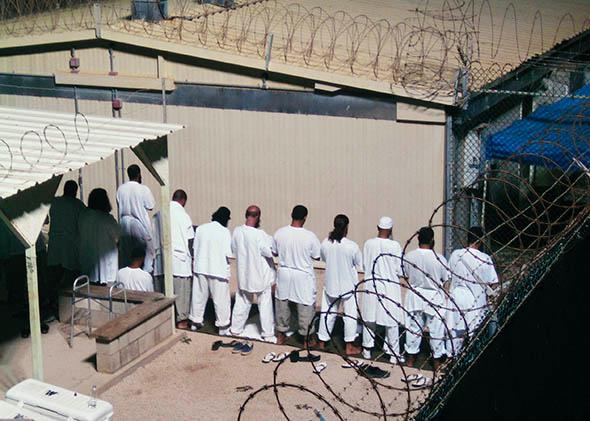

Third, Guantanamo Bay. President Obama, like President George W. Bush before him, wants to shut Guantanamo Bay because he believes that it sends the wrong message about American values and does not advance U.S. security. Some of the detainees are harmless and can safely be bundled to foreign countries. Others are dangerous but could be tried in U.S. courts and transferred to prisons on U.S. soil. So far, however, few detainees have been removed. Obama needs to act more aggressively if he wants to keep his promise to close the prison.

Can Obama really do these things without Congress’ participation? The answer is yes, but for different reasons. For the illegal aliens, Obama can invoke the enforcement power conferred on him by the Constitution. Congress makes the law, but the president enforces it (“executes,” in the Constitution’s lingo), and it is widely agreed that the power to enforce is discretionary. Indeed, all recent presidents have failed to enforce the immigration laws except against criminals and in other serious cases—that’s why more than 10 million people reside in this country unlawfully. Obama would merely be making an announcement of what is already the case—that nearly all illegal immigrants, aside from serious criminals, are not deported.

Photo by Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images

For climate regulation, the president can rely on a statute—the Clean Air Act, which authorizes him to impose regulations on industries that causes pollution. Since the Supreme Court ruled that carbon emissions count as pollution, the president’s statutory authority is unquestioned.

For Guantanamo Bay, the president’s legal authority is more complex. He could cite his commander-in-chief power under the Constitution and argue that Congress cannot force him to detain enemy combatants he believes should be released. It was on that basis that he recently traded five Guantanamo detainees for Bowe Bergdahl, an American solider captured by the Taliban. There are also various statutory loopholes he could exploit. Indeed, the president could declare the war with al-Qaida over, and in this way remove the legal foundation for the remaining Guantanamo detentions. It is perhaps for this reason that the president has announced that he wants a statute from Congress that authorizes the use of force against ISIS. Once that statute is in place, he could formally declare the war with al-Qaida over, and would be able to drop the fiction that ISIS and al-Qaida are the same entity, which he used to justify relying on the statute that authorizes the use of military force against al-Qaida for hostilities with ISIS.

One major constraint on all these actions is that Obama can sustain them only as long as he remains in office. Since he can’t make law, the next president will not be bound to continue them. However, the practical significance of this constraint is nil. If Obama releases Guantanamo detainees, the next president will not be able to put them back in Guantanamo. He or she could reopen Guantanamo and repopulate it with a new batch of terrorists, but the Guantanamo experiment was a failure, and no future president will repeat it.

Similarly, it would be difficult for a future president to withdraw climate regulations or start deporting the people whom Obama has permitted to stay. Once polices likes these are put in place, they attract constituencies and gain political momentum. Businesses that legally employ otherwise illegal immigrants would object to their deportation. Businesses that have incurred significant costs to comply with climate regulations will object if competitors that enter the industry are no longer subject to them because the regulations have been withdrawn.

If Obama can do all these things, why hasn’t he already done them? The answer is politics. All of these actions are intensely controversial, and Obama could have badly hurt Democrats in the recent elections by pushing them through, as well as undermining his own support among the public. But the elections are over, and now Obama has a free hand. While he might, of course, hurt Democrats in the 2016 elections if he acts aggressively today, the public has a short memory, and Obama might be more interested in securing his legacy than helping his party. The trick now is to move forward without putting so many Democrats in political trouble that they would form a veto-proof supermajority with Republicans to counter Obama’s policies with legislation. If Obama can thread this needle, then, whether you like his policies or not, future historians will regard him as one of the most consequential presidents of modern times.