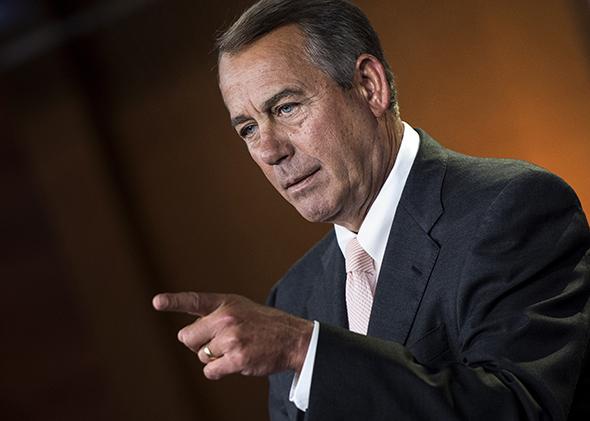

House Speaker John Boehner wants the House of Representatives to sue President Obama for overstepping the limits of executive authority. Can he do this? Will he win? Does it matter? Yes, he can do it, but no, he won’t win. And no, his lawsuit doesn’t matter, but that in itself tells us a lot about presidential power.

Boehner initially was vague about which of the president’s actions he planned to challenge, but Thursday he released a bill that targeted the president’s failure to enforce a few provisions of Obamacare—for example, the employer mandate, which was delayed until 2015 because more time was needed for businesses to prepare for it. It might seem strange that a Republican would want to sue President Obama for giving businesses a break, but the Obamacare complaint stands in for a larger argument that the president disregards his constitutional obligations. As Boehner wrote in an op-ed for CNN:

In the end, the Constitution makes it clear that the President’s job is to faithfully execute the laws. And, in my view, the President has not faithfully executed the laws when it comes to a range of issues, including his health care law, energy regulations, foreign policy and education.

Obama’s critics argue that, in addition to Obamacare, the president has refused to enforce the immigration laws against a large group of aliens who arrived in this country as children, and in this way unilaterally implemented a piece of legislation—the DREAM Act—that died in Congress. He has issued waivers to states freeing them from compliance with the test score requirements of No Child Left Behind. He released prisoners from Guantánamo Bay as part of a prisoner swap without giving Congress the statutorily prescribed 30-day notice. He refused to enforce federal drug laws against some users of marijuana in states that have legalized marijuana. He refused to defend the Defense of Marriage Act before the Supreme Court. He used military force in Libya in defiance of the War Powers Act. He has ordered the assassination of American citizens abroad, through drone killings, without granting them due process.

To bring a lawsuit, however, one needs more than general complaints about the action of another person. Any litigant, including Boehner, must satisfy numerous legal requirements and, above all, be able to point to a law that the defendant violated. A court will almost certainly dismiss any lawsuit of the sort Boehner intends because the House of Representatives lacks “standing” to bring a suit—meaning that it has not suffered a concrete injury as a result of Obama’s actions.

But standing aside, the most interesting question is whether Boehner’s legal claims could have any merit. Boehner argues that Obama violated two clauses of the Constitution—one that requires him to take an oath to “protect and defend the Constitution,” and another that requires him to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.”

The nub of the argument lies in the idea of faithful execution of the law, and this is where the president is most vulnerable. Immigration law forbids foreigners to enter and settle in this country without authorization based on criteria laid out in statutes. The president tried to persuade Congress to amend this law to carve out an exception for a young and sympathetic group of undocumented immigrants. Congress refused. The president then decided to stop enforcing the law against this same group of people—in this way implementing the policy that Congress refused to consent to. Isn’t this a failure to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed”?

Probably not, because another legal principle cuts another way. Courts have repeatedly held, in the Supreme Court’s words, that “the Executive Branch has exclusive authority and absolute discretion to decide whether to prosecute a case.” To understand this principle, one must first recognize that technical violations of the law vastly outstrip the resources of the executive to go after them. People speed on the highways, smoke dope, and cheat on their taxes in vast numbers. Corporations pollute, defraud investors, and evade taxes. More than 10 million people illegally reside in the country, most of them illegally employed by individuals and businesses. The executive branch lacks the resources to investigate, catch, and prosecute all these people. It simply can’t.

So the government must make choices. Many of those choices—like spending more resources on investigating murders than on burglaries—are uncontroversial. But others quickly take on politically charged overtones. What if the government says that it will investigate cocaine dealers but not marijuana sellers, because marijuana possession is not as serious? Or that it will use most immigration resources to deport undocumented immigrants who commit violent crimes because they are more dangerous than those who do not?

Perhaps these are “policy” judgments of the sort that should be made by Congress. There is a pervasive slippery-slope worry that if the president can refrain from enforcing immigration laws against DREAM-ers, then he can also refuse to enforce corporate taxes (if he is a Republican) or laws that give mining firms access to mineral resources on public lands (if he is a Democrat). Indeed, if you accept the principle of prosecutorial discretion in the broadest sense, the president could decline to enforce campaign finance laws against his supporters, or instruct his subordinates to violate the law and refuse to prosecute them. Indeed, President Obama did refuse to prosecute Bush administration officials who appear to have violated laws against torture and surveillance. (The Republicans don’t seem to be upset about this particular exercise of presidential discretion.)

And yet the government would almost certainly self-destruct if courts tried to force it to enforce every law and to comply with every rule that Congress creates. The Dodd-Frank Act ordered regulators to issue hundreds of new regulations to prevent financial institutions from causing another global meltdown. That was in 2010. Today, 280 deadlines for the new rules have passed and 127 of them have been missed. The regulators simply couldn’t handle so many complex rules and chose to break the deadlines rather than issue bad ones. (Republicans have not complained about this exercise of executive discretion, either.) Complex new programs must be adjusted in light of unanticipated events. What exactly is so different about Obamacare?

Scholars have labored to draw a distinction between justified and unjustified executive discretion. Law professor Zachary Price has recently argued that the president can decline to prosecute on a case-by-case basis, because of lack of resources or difficulties of proof, but cannot adopt a policy of refusing to enforce this law or that. This is surely an unworkable distinction. It would turn an official policy of leaving be people who drive 56 miles per hour in a 55 mph zone into a violation of the Constitution. Why make judgments on a case-by-case basis when rules can be set out in advance?

The confusion in Price’s article and Boehner’s lawsuit hinges on a pervasive misunderstanding of how our government works. Forget what you learned in seventh grade: It’s simply not the case that Congress sets policy and the president executes it. The two branches battle over policy, using all means at their disposal. The laws themselves are frequently vague and loose. In the end, the president enforces most of the laws in an even-handed way because most laws are popular—that’s why they were enacted in the first place. If you don’t believe me, consider how rare it is for presidents to use the pardon power, which is without doubt discretionary, for partisan or ideological ends. President Obama has not gone beyond public opinion—for example, by releasing prisoners from Guantánamo Bay—because he fears a political backlash, not because it’s illegal.

This conflict is baked into our system. It’s a result of the founders’ decision to give the executive and the legislature different sources of political authority. This is how our government differs from a parliamentary system, in which the prime minister operates at the pleasure of the legislature. If you want to blame someone, don’t blame Obama. Blame the Constitution.