Filibuster reform is a huge victory for progressives, according to David Weigel. Emily Bazelon agrees. Yet some conservatives not caught up in the immediate political bickering seem pretty happy about it too. Who loses? Most likely those in the center, meaning most of us.

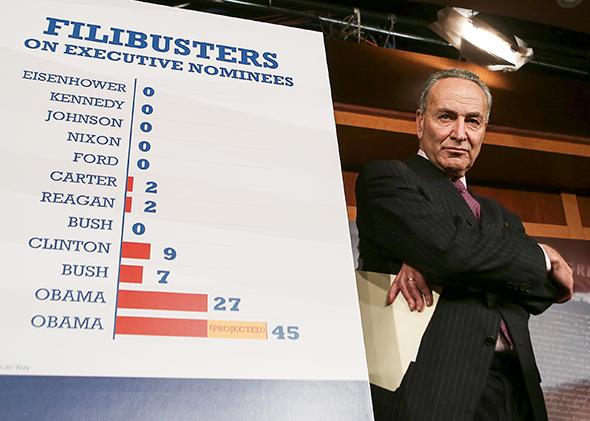

There are two arguments for why the Democrats were right to change the Senate’s rules so that a minority can no longer block the appointments of judges (except on the Supreme Court) and executive branch officials. The first is that the existing scheme depended on cooperation with Republicans, and Republicans have stopped cooperating. If that is why, then I agree that the Democrats acted in their own best interests.

The second argument is that the existing scheme was not “democratic” because it allowed a minority of senators (many of them from sparsely populated states) to block the will of the majority. This argument is a bad one.

Majority rule is not intrinsically democratic—it is not always the best way for a group of people to make decisions. Our political system is shot through with supermajority rules, like the two-thirds rule that the Senate uses for approving treaties and convicting officeholders after an impeachment. The system of bicameralism established by the Constitution, with a presidential veto, effectively means that legislation must have supermajority support because different constituencies elect the two houses and the president.

Indeed, consensus and unanimity are very attractive voting rules because they ensure that decisions must make everyone better off—otherwise, voters will block them. That is why consensus is the norm for small bodies like the law school faculty I belong to. It’s true that for larger groups, as the scholars James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock pointed out long ago, this rule leads to gridlock. The closer to a simple majority, the easier decision-making becomes. But there is a cost: It also becomes easier for people who manage to form a majority to make decisions that cause significant harm to the minority.

To provide an extreme example, under a pure system of majority rule 51 percent of the population could pass a law that transferred the wealth of 49 percent of the population to the majority. If at the next election, the other side managed to win, it could expropriate the wealth back. The resulting instability, as different groups took turns expropriating each other’s wealth, would impoverish the country over time. If one group never took a turn winning, then the outcome would be inequitable as well as bad for the public at large. If all of this sounds too implausible to be of concern to you, then remember Jim Crow in the South, and the many decades disenfranchised African-Americans spent as electoral losers.

When progressives stop cheering, they may remember that they are historical opponents of majority rule. It was “tyranny of the majority” that produced racist laws in the South or, if you want, the federal Defense of Marriage Act. Conservatives also traditionally objected to majority rule. For them the problem was the tyranny of the property-less majority that resulted in laws that repudiated debts, violated contracts, and expropriated property before the ratification of the Constitution put a stop to all of this. Along with the two-chamber structure, fear of unconstrained majorities on both sides of the political aisle explains many more features of the American political system—the presidential veto, federalism, the rise of judicial review, and, yes, the voting rules in the Senate.

Because our bicameral system, plus presidential veto, already tilts the U.S. system toward supermajority rule, opponents of the filibuster argued that an additional 60 percent rule in the Senate was unnecessary. It’s in fact hard to know. For ordinary legislation, I tend to agree—though filibuster reform has not (yet) reached ordinary legislation. Maybe this is also true for executive branch officials who serve limited terms. But the case for judges is quite different.

Federal judgeships are already anti-majoritarian positions. If a majority selects a judge, then the majority’s preferences will be embodied in the ideology of that judge for as long as that judge is in office—a long time, given lifetime tenure. Majorities in the future will have to contend with this judge vetoing their legislation, and while they will be able to confirm their own judges as well, the upshot is that the past will always exert a dead hand on the present, stymying legislation that does not conform to 30-year-old political views.

This is quite different from lawmaking. If majority is the rule, then a future legislative majority can overturn an earlier majority’s law as easily as the earlier majority passed it. So a majority cannot extend its preferences across time in legislation.

And this is why the use of majority rule to confirm judges is troubling. A majority in the Senate will systematically approve more extreme judges than a supermajority will. This is obvious enough when the Senate is split. With the filibuster, if a Republican president faces a Senate with 59 or fewer Republicans, he will need to nominate someone a Democratic is willing to vote for. Under the new system, the Republican president can appoint someone so extreme that even eight or nine Republicans vote against him. And of course the same goes for a Democratic president.

The upshot is that because of the Senate’s new rule, we will see more ideological extremity on the bench—in both directions. This is bad for litigants, whose fates will depend more than ever on random assignments of judges to panels and bad for the law, as it will become more and more difficult to predict how judges will rule. Hair-breadth electoral outcomes will project the undiluted ideological commitments of the winners farther in the future than ever before.

And if the outcome is good for extremists, they will mostly be Republicans. Next time Republicans control the presidency and the Senate, they will appoint ideologically extreme judges. True, Democrats could cancel out this effect by appointing extremely liberal judges when they are in power, but recent history suggests that Democrats do not care as much as the Republicans about appointing ideologically extreme judges. Unless this changes, picture a federal appellate bench composed of numerous Antonin Scalias and Clarence Thomases, not fully offset by Elena Kagans and Stephen Breyers.

The collapse of the filibuster rule is the result of a breakdown of cooperation between Democrats and Republicans, not of the long-delayed realization of Democrats that they gain more from majority rule for judicial appointments than they lose. It’s another sign—along with the debt ceiling standoff and the government shutdown—that our political institutions are failing us.