Last week, the Obama administration asked the Supreme Court to review a lower court ruling that several so-called recess appointments made by the president were invalid. The court’s opinion is a case study of bad legal reasoning, and the Supreme Court is likely to reverse the decision. The opinion shows the increasing and increasingly malign influence of a theory of legal interpretation known as originalism. Bear with me through the legal minutiae, and you’ll discover how a major conflict between the president and Congress can turn on the meaning of the word the.

The case arose after the National Labor Relations Board held that a firm called Noel Canning violated the law during collective bargaining negotiations with the Teamsters. The court ruled that the holding was invalid because the NLRB lacked a quorum of three members. Five people sit on the NLRB, but three of them had been appointed by President Obama in violation of the appointments clause of the U.S. Constitution.

Generally speaking, the Constitution provides that the president may appoint high-level officials only with the consent of the Senate. However, the recess appointments clause provides that when Congress is in recess—that is, is not meeting—the president may fill a vacancy without obtaining consent, although the appointee may remain in office only until the end of the next session, which usually means a year or two. (Normally, an appointee will serve a longer term—for example, four years, or at the president’s pleasure.)

Members of Congress, like kindergartners, get recesses. But unlike kindergartners, they get to decide when these recesses occur. For most of its history Congress has met in one session per year, with each session starting in January (or sometimes later in the winter) and ending in December (or sometimes earlier in the fall). The period between the end of one session and the beginning of the next is called the intersession recess. Congress also sometimes adjourns in the middle of a session. These breaks, called intrasession recesses, may be as short as an hour for juice and cookies or as long as weeks while members vacation or campaign. Throughout history, presidents have made appointments during intersession recesses, and since the 1940s they have also frequently made appointments during intrasession recesses longer than three days or so.

Like his predecessors, Obama has made recess appointments. In 2011, the Republican-led House blocked the Senate from formally ending its 2011 session and forced it to hold a pro forma session every three days from Dec. 20, 2011, to Jan. 23, 2012. A pro forma session is one in which no business is conducted—a senator just shows up and bangs the gavel. When the 2012 session began on Jan. 3, 2012, the 2011 session automatically expired, with the result that no intersession recess took place—there was literally no time between the two sessions—and hence the president could not make an intersession recess appointment. Meanwhile, because the pro forma meetings kept the intrasession recesses shorter than three days, the president could not make an intrasession recess appointment without violating tradition.

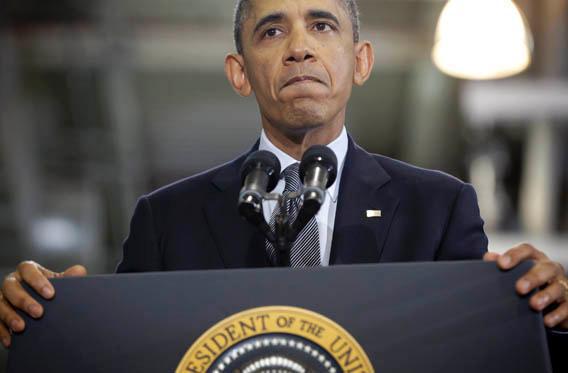

Obama nonetheless made several recess appointments on Jan. 4, 2012—three to the NLRB, and also the head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, a new agency created by Congress to protect consumers from abusive credit practices. The Obama administration argued that the Senate cannot pretend it is in session when it really isn’t in session. On Jan. 4, 2012, it was in fact in recess—an intrasession recess to be sure, because the new session had begun the day before, but if one ignores the pro forma meetings, an intrasession recess long enough to justify an appointment.

The Constitution’s recess appointments clause provides that: “The President shall have Power to fill up all Vacancies that may happen during the Recess of the Senate, by granting Commissions which shall expire at the End of their next Session.”

To get at the original understanding of the text, the court started with the language, which normally trumps other evidence about the founders’ intentions. The court first argued that the language refers to the recess, not a recess. Thus, the founders could have had only one particular recess in mind, and that recess must be the one that takes place between the two sessions. Because Congress chose not to leave a gap between the 2011 session and the 2012 session, the recess could not have taken place.

Two of three judges sitting on the panel further argued that by providing for recess appointments only to vacancies “that may happen during the Recess,” the founders intended to limit appointments to vacancies that open up during the intersession recess. But the vacancies that Obama filled could not have opened up during an intersession recess because no such recess took place.

Both of these readings are possible; they may even be plausible. The administration’s argument—that the recess means any recess, and that the vacancies that happen during the recess are vacancies that exist during the recess—is also consistent with the language. But it’s strange to think that “the Recess” means only one (intersession) recess when, even under the court’s interpretation, there have been hundreds of intersession recesses—every year there was another intersession recess up until last year—and the founders surely expected numerous such recesses unless they believed that the republic would collapse in 1791. Indeed, the Constitution repeatedly refers to “the Congress” and “the President.” If the court’s interpretation of “the” as “the single” were correct, this would mean that the founders expected only one Congress and one president to ever come into existence, when in fact (as other language makes clear) they contemplated numerous Congresses (one every two years) and numerous presidents as well.

But here’s the point. It defies belief that the founders intended to constrain recess appointments by using the word the rather than a, or by using the word happen rather than exist. If the founders had feared that the president would abuse the recess appointments power in order to create a tyranny, they would have made their intentions to constrain the president a bit more explicit.

In fact, we know next to nothing about what the founders intended because of the paucity of contemporary documents revealing their intentions. We can surmise that they wanted the president and Senate to share the appointments power but also that they recognized that the president might need to make appointments to keep the government running when the Senate was out of session. Both the court’s and the Obama administration’s readings of the clause are consistent with this general purpose, so it is idle speculation to draw on the original understanding to resolve the dispute.

What could be the source of decision then? Presidents from both parties have been making intersession and intrasession recess appointments for decades, and Congress has acquiesced until now. Because of the ambiguity of the Constitution and the natural evolution of the relations between branches, courts normally defer to historical practice. That would have been the appropriate thing to do here.

The more interesting question is why the court broke with this practice. Jeffrey Toobin detects “right-wing judicial activism.” Republicans hate a lot of agencies—and especially the NLRB and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. If Republicans in the Senate can block appointments, they can shut down these agencies, unless the president can make recess appointments—and maybe the three Republican judges on the court sought to assist their pals in Congress. However, the strategy of denying recesses long enough to permit recess appointments originated with the Democrat-controlled Senate during the Bush administration. The court must have realized that its ruling will hurt a Republican president as much as a Democratic president.

The opinion also contains some boilerplate about presidential self-aggrandizement, which each party worries about when the other party holds the White House. But it’s hard to imagine the NLRB or the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau as instruments of tyranny. Was it Hitler or Stalin who banned prepayment penalties for adjustable-rate subprime mortgages?

I suspect that the judges actually believed their own reasoning. And that is the most unfortunate thing about this case. The influence of originalism—the idea that the Constitution should be understood according to its original meaning—would not be so harmful if courts also acknowledged that the document is filled with ambiguities and confined themselves to enforcing only the clear rules, like the rule that the president’s term lasts four years. (Sorry, I mean a president’s term.) But driven by the current mania to find an original meaning, the court attributed to the text a level of precision that does not exist. The outcome is not necessarily rulings that are ideologically biased—just rulings that make no sense.