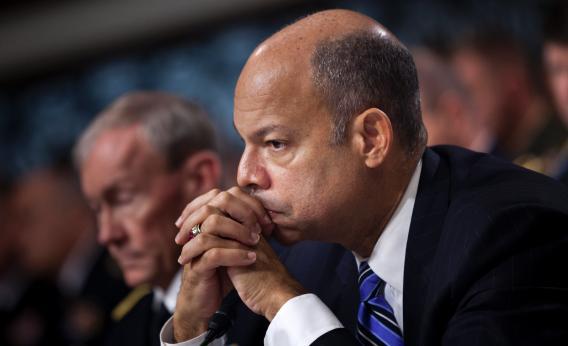

In a recent speech that generated some excited chatter in the blogosphere, Jeh Johnson, the Pentagon’s chief lawyer, hinted that the armed conflict with al-Qaida may be coming to an end:

I do believe that on the present course, there will come a tipping point—a tipping point at which so many of the leaders and operatives of al-Qaida and its affiliates have been killed or captured, and the group is no longer able to attempt or launch a strategic attack against the United States, such that al-Qaida as we know it, … has been effectively destroyed. At that point, we must be able to say to ourselves that our efforts should no longer be considered an “armed conflict” against al-Qaida.

The rose-colored-glasses perspective on this is as follows. The president obtained authority to wage war against al-Qaida from a statute called the Authorization for Use of Military Force, which Congress enacted shortly after 9/11. The AUMF triggered the president’s commander-in-chief power, which enables him to detain enemy combatants indefinitely and kill them with drones and other weapons. If the conflict with al-Qaida ends, then the president loses these authorities, must release or try detainees at Guantánamo Bay, and must stop using drones to kill people. Counterterrorism will go back to the domain of law enforcement, where it resided before 9/11. As Johnson himself notes, this means that terrorism will be handled by the police, and be governed by law enforcement norms—including Miranda warnings, search warrants, charges, trials, prison sentences, and all the other features of civilian due process. Civil liberties would awaken from its 11-year slumber.

But it is too early to celebrate. As Harvard law professor and Bush Justice Department official Jack Goldsmith has pointed out, Johnson’s speech contains many hedges and equivocations. Most important, although Johnson notes that the “core” of al-Qaida has suffered a significant lashing, its affiliates are alive and well, especially in the Middle East, where they appear to be flourishing. The AUMF identifies the affiliates of al-Qaida as the enemy, as well as al-Qaida itself. As long as those affiliates remain in existence, the United States will be at war with them. And because “al-Qaida” has become a kind of brand that any group can lay claim to, al-Qaida affiliates will be around as long as radical Islam is.

Moreover, even if al-Qaida and its affiliates are destroyed, it will make little difference for the president’s authority to use military force against future terrorist threats. The president will retain his authority under the Constitution, Article 2 of which has been interpreted to give the president the power to use military force against security threats even in the absence of congressional authorization. Johnson implicitly recognizes this point when he notes that if law enforcement can’t handle future terrorist threats, “our military assets [will be] available in reserve to address continuing and imminent terrorist threats.”

It is true that there is intense controversy among lawyers as to the scope of the president’s constitutional authority, with many on the left arguing that it is limited to repelling sudden attacks. But this is legal posturing. The president has strong incentives to protect Americans from terrorist attacks and the public largely approves of aggressive action, and therefore no one—not the public, nor Congress, nor the courts—will make a fuss if the president uses military force to counter a new terrorist threat to come.

But there is a broader mistake in Johnson’s speech and the reaction to it. This error lies in seeing our era of lesser civil liberties as stemming from al-Qaida in particular. Al-Qaida was merely the symptom of two larger changes in world affairs. The first is the advance of weapons technology, which has made it easier for foreign terrorist organizations to miniaturize, hide, transport, and use dangerous weapons against civilian targets. And the second is globalization, which has thrust the United States into the affairs of unstable countries with murderous conflicts, putting it in the crosshairs of unhappy groups., These two factors have made it impossible to go back to the era before 9/11.

Ordinary law enforcement methods are not effective against foreign terrorists in the modern era because foreign terrorists can train, recruit, obtain weapons, and hatch their plots in foreign countries with weak governments that cannot fully control their territory, making it impossible for the United States to demand extradition or conduct joint law enforcement operations. This puts the United States to the choice of either waiting for an attack to take place and hoping to thwart it at the last moment, or launching preemptive military operations abroad. In light of the destructiveness of the kinds of modern weapons that could be used against us—including chemical and biological variants—the choice is not very difficult.

The Clinton administration recognized these problems in its time, firing cruise missiles at al-Qaida camps in Afghanistan in 1998, and at a plant in Sudan thought to be used to manufacture chemical weapons for al-Qaida. The Clinton officials did not detain foreign terrorist suspects indefinitely, but they did ship them off to countries that would take care of them, one way or the other.

The Bush administration took the Clinton approach to its logical conclusion by fully militarizing counterterror operations. Realizing that security threats could come from any foreign terrorist organization, not just al-Qaida, it insisted on the president’s broad authority to counter any security threat, rather than relying solely on the AUMF. That is also why the Bush administration supported new laws, including the FISA Amendments Act and the Patriot Act, which enabled intelligence and law enforcement authorities to respond to, and take advantage of, new technologies. These statutes will remain on the books long after al-Qaida is vanquished.

The Bush administration also put into place institutional changes. It expanded the paramilitary arm of the CIA, revitalized the military’s special forces, reorganized intelligence gathering, and launched the drone program. These changes will also outlast al-Qaida. The idea of calling the conflict with al-Qaida a “global war on terror,” rather than a war on al-Qaida or a war on Islamic extremism, reflected the sense of a new era of wider danger. And while the Obama administration rejected the rhetoric, it has embraced most of the Bush administration’s legal and institutional initiatives.

The United States may finally land a decisive blow against the core of al-Qaida, and could conceivably even lop off its many hydra heads around the world. But the United States will always be vulnerable to foreign terrorism. The 9/11 attacks merely woke us up to this amorphous threat. To protect the country, the public and the political class acquiesced in expanding presidential power and limiting civil liberties. These changes will remain with us as long as the threat does.