A few weeks ago, two Washington Post journalists who barely three months before Republicans lost control in Congress in 2006 released a book calling the party “the New York Yankees of American politics—the team that, at the start of every season, has the tools in place to win it all,” reported that the right is back. Their story, headlined “Conservative groups reaching new levels of sophistication in mobilizing voters,” presented a roster of outfits whose efforts could prove a counterweight to Barack Obama’s fearsome ground program.

Two days later, the New York Times described one of these groups in a story of its own. In 2009, scandal-tarnished former Christian Coalition impresario Ralph Reed founded the Faith and Freedom Coalition and, according to the Times, “now plans to unleash a sophisticated, microtargeted get-out-the-evangelical-vote operation he believes could nudge open a margin of victory.” The Times story explained in unusual detail the method behind Reed’s data operation:

To identify religious voters most likely to vote Republican, the group used 171 data points. It acquired megachurch membership lists. It mined public records for holders of hunting or boating licenses, and warranty surveys for people who answered yes to the question “Do you read the Bible?” … It drilled down further, looking for married voters with children, preferably owners of homes worth more than $100,000. Finally, names that overlapped at least a dozen or so data points were overlaid with voting records to yield a database with the addresses and, in many cases, e-mail addresses and cellphone numbers of the more than 17 million faith-centric registered voters—not just evangelical Protestants but also Mass-attending Catholics.

Those who have actually worked with voter data were a bit less awed by this description of Reed’s process. One Republican consultant describes it as “backward microtargeting.” Acquiring membership lists from allies is a decades-old practice in coalition politics, and the central tactic—sending voter guides to people on church rolls—last seemed cutting-edge when Newt Gingrich’s career was first on the ascendancy.

“There is nothing new in that article,” says one veteran of the Bush campaigns who spoke anonymously to candidly critique a fellow Republican’s program. “It was pretty much what we did in 2000.”

Indeed, the Reed approach seems oblivious to the most important innovations that have taken place in the years since. Microtargeters often describe their project as “look-alike modeling,” because the goal of using statistical algorithms is to discern patterns in an existing sample (like people on a church list) that can then be used to find people who resemble them in other populations, about which there is less information available. There is significantly less value in acquiring data that confirms that your targets look the way you thought they would.

The consequence of such primitive targeting was felt recently at one mailbox in the Richmond suburbs. The letter was addressed to a woman who attends Mass and subscribes to a Catholic Charities newsletter, is married with children, and lives in a home worth more than $100,000. She may have racked up a lot of points in Reed’s categories, but there’s one other publicly available fact about her—she regularly votes in Democratic primaries for federal and state office—that an algorithm would likely have treated as more predictive of her political attitudes than her income or church affiliation. Reed’s get-out-the-vote mail had targeted a phone-banking Obama supporter.

All targeting carries the risk of missing the mark, and there are regularly voters whose actual attitudes defy the predictions of statistical models. But regular misfires by Republicans—which at best only waste resources and at worst mobilize Democrats who might not have voted otherwise, or provoke a backlash among those still persuadable—illustrate a gap between how the right and left practice politics in the 21st century. Contrary to the wishful intimations of the Post and Times stories, while the groups on the right could conceivably catch up with Obama and his allies in the scope and funding of their ground-level activities, in terms of sophistication they lag too far behind to catch up in 2012.

In fact, when it comes to the use of voter data and analytics, the two sides appear to be as unmatched as they have ever been on a specific electioneering tactic in the modern campaign era. No party ever has ever had such a durable structural advantage over the other on polling, making television ads, or fundraising, for example. And the reason may be that the most important developments in how to analyze voter behavior has not emerged from within the political profession.

“The left has significantly broadened its perspective on political behavior,” says Adam Schaeffer, who earned graduate degrees in both evolutionary psychology and political behavior before launching a Republican opinion-research firm, Evolving Strategies. “I’m jealous of them.”

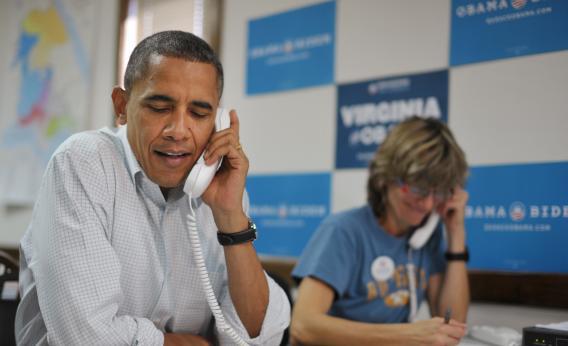

Photo by David Greedy/Getty Images

Schaeffer attributes the imbalance to the mutual discomfort between academia and conservative political professionals, which has limited Republicans’ ability to modernize campaign methods. The biggest technical and conceptual developments these days are coming from the social sciences, whose more practically-minded scholars regularly collaborate with candidates and interest groups on the left. As a result, the electioneering right is suffering from what amounts to a lost generation; they have simply failed to keep up with advances in voter targeting and communications since Bush’s re-election. The left, meanwhile, has arrived at crucial insights that have upended the conventional wisdom about how you convert citizens to your cause. Right now, only one team is on the field with the tools to most effectively find potential supporters and win their votes.

***

The first dramatic expansion of the campaign brain in the 21st century came from the world of commercial marketing. Private-sector data warehouses, created initially to generate credit ratings and later used by direct-mail marketers, had collected far more information on voters than had ever been available to campaigns through traditional political sources. Improvement in database architecture and computing power made it possible to run statistical models that could churn through tens of millions of these consumer records at once. While operatives on both sides tapped into this capacity, it was Republicans—thanks in part to close ties between some of the party’s public-opinion researchers and the private-sector firms that agglomerated consumer data—who fully exploited its potential first.

Following Bush’s re-election in 2004, Democrats worked assiduously to catch up with what they considered the Republicans’ structural data advantage, developing their own relationships with commercial data vendors and refining their algorithms. Today, the most advanced political campaigns have in certain respects surpassed consumer marketers in their ability to predict individual preferences, and you’re as likely to see a Fortune 500 company trying to uncover the secrets of the Obama data operation as the other way around.

Yet the campaign brain has continued to expand. The most important methodological and conceptual breakthroughs in recent years have originated in the academy, specifically through insights from behavioral psychology and the use of field experiments. Since 2004, myriad advocacy groups and consulting firms on the left have joined forces and launched a series of nominally for-profit private research institutions devoted to campaign tactics. The most impressive among them, the Analyst Institute, was created to link the growing supply of academics interested in running randomized-control trials to measure the efficacy of political communication with the demand of left-wing institutions eager for empirical methods to test their programs. These partnerships have birthed a generation of political professionals—many baptized in the unprecedented pools of data collected by Obama’s 2008 effort—at ease with both campaign fieldwork and the techniques of the social-science academy.

Photo by Jewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images

This summer, a top Republican analyst stumbled upon a job notice posted by the left-wing League of Conservation Voters. The position was Targeting and Data Director. The analyst looked admiringly at the description of the job, especially its duties to “explore and devise opportunities to test and measure the impact of all of our programs, including working closely with entities such as the Analyst Institute.” He marveled at what that language revealed about the sophistication of his rivals’ intellectual enterprise. “One thing the left—Catalist, Analyst Institute, New Organizing Institute—has done very well is training and seeding of this sort of stuff, this sort of philosophy,” said the analyst, who asked not to be identified because of election-season attachments but has worked closely with the Republican National Committee and presidential campaigns.

Dozens of such postings exist in what some call the “progressive data community.” I asked the Republican analyst what analogous jobs existed among the institutions of the right. How many of the League of Conservation Voters’ ideological foes—like the Chamber of Commerce, or their frequent allies at the National Rifle Association or the Faith and Freedom Coalition—have data managers and targeting directors with similar mandates to test and measure?

“I honestly don’t know,” the analyst replied. “If I had to guess? Zero.”

The Analyst Institute’s centrality in the left’s research culture has enshrined the use of randomized field experiments as the best tool for measuring what actually moves voters. And the biggest conceptual contribution this body of experimental work has made is to cleanly separate what a voter does in election season into two discrete phases: choosing among candidates and deciding whether to vote. Experiments have shown that giving voters more information about candidates or issues or the stakes of the election does little to adjust their likelihood of casting a ballot. To budge a nonvoter out of complacency, campaigns have learned, they have to use psychological techniques focused on getting someone to do something he or she is not used to doing. There’s one set of tools for changing opinions, and another for modifying behavior.

This basic paradigmatic distinction appears lost on many of those who direct campaign activity on the right. In an interview, Ralph Reed said that the Faith and Freedom Coalition’s microtargeting project had identified 10 million citizens in 18 states comprising a “turnout universe” that would receive at least six get-out-the-vote contacts, starting with a voter guide outlining differences between Obama and Romney on 10 issues, including taxes and abortion. “We’re looking for anyone who is registered to vote and who would benefit from this information,” he explained. I asked why, if the goal was to mobilize infrequent voters who had already been profiled as likely to be socially conservative, was he sending them information designed to persuade them that Romney was better on the issues they cared about. “I don’t know if it could be called persuasion,” he replied. “We think we need to educate them on where the candidates stand.” If Reed had been aiming to play dumb in the interview to obscure his group’s tactics, he succeeded.

***

In August, a Virginia playwright and newspaper editor named Dwayne Yancey was surprised to see a series of glossy direct-mail pieces from the Romney campaign arrive at his home outside Roanoke. The first two brochures had to do with coal mining, which struck Yancey as irrelevant to him or his family: They live four hours from the nearest mine, and coal production carries little of the romantic imagery for Yancey that have led Republicans to believe it was a potent issue in West Virginia and Kentucky. “At first I thought it was simply urban ignorance of rural Virginia,” says Yancey, who wrote about the mailers on the website of the Roanoke Times, where he works. Then more mail came to the Yancey household from Romney’s campaign, on more plausible subjects: about the deficit, about Medicare and Social Security, and one item that attacked Obama for being “All Welfare. No Work.” The thing that puzzled Yancey most about all of the Romney mail was the person in his household had been selected to receive it. Every piece, from coal to welfare, had been addressed to his 23-year-old daughter.

Photo by Emmanuel Dunand/AFP/Getty Images.

His daughter, whom I’ll call Sarah, settled on her choice in the presidential race long ago, but the campaigns had no way of knowing that. Sarah is private about her political views; she does not respond to phone calls from campaigns and does not believe she has given the Romney or Obama camp an indication of her preference through any other channel, like signing up on a website. She remains something of a cipher in the piles of data through which campaigns sift in the hunt for clues about how they ought to engage her. Virginia does not allow citizens to register with a political party, and although Sarah had voted by mail in every election since turning 18 she had voted in only one primary, for the Democrats’ 2008 nomination. She has refrained from partisan activity like donating to a candidate or joining an ideologically-minded membership group. And given a limited buying history and the fact that she has never had a home in her name there was scant information in the consumer databases that often help round out a voter portrait. (Yancey provided me with his daughter’s name so I could see what information was available about her in political and commercial databases, and she discussed her views so long as I agreed not to publish any of her identifying characteristics.)

The available information about Sarah would seem, at first glance, to produce conflicting indicators. Sarah is a young woman and has voted in a Democratic primary, which would probably point her toward Obama. But she lives in a precinct that votes overwhelmingly Republican, which would nudge things back toward Romney. The algorithms that automate these assessments based on available data are similarly indecisive. One Democratic targeting firm’s statistical model predicts a 59 percent likelihood Sarah would self-identify as a Democrat.

Yet only one of the two presidential candidates looked over the summer at this profile of a centrist, albeit one who leaned slightly left, and saw a voter whose mind was up for grabs. The Romney campaign had concluded that Sarah was the type of voter it could persuade—either because she was actually undecided among the candidates, she was a soft Obama backer who could be convinced to defect, or a soft Romney backer whose support needed to be shored up. Yet the Obama campaign didn’t launch any parallel efforts to persuade this supposed middle-of-the-roader. Democratic targeters may have looked at her and concluded that her vote was not in question—or that the campaign had a better way of reaching her to make its case than issue-based direct mail. Those calculations, and the years of experimental findings informing them, may reflect better than anything the massive gap between how Democrats and Republicans understand the challenge of finding voters to convert to their sides.

***

The differences in the two campaigns’ approaches to Sarah Yancey may owe more to Aaron Strauss than anyone else. Strauss is precisely the type of person who does not go to work in Republican campaigns. In 2004, the recent college graduate had used his skill with computers to manage Howard Dean’s New Hampshire voter information, earning the nickname Data from the campaign’s field organizers. Afterward Strauss went to work for Mark Mellman, who served as the lead pollster for John Kerry’s presidential candidacy. Then Strauss returned to school, choosing to study at Princeton with Kosuke Imai, who seeks methodological solutions to the ongoing problems political scientists face when trying to isolate cause and effect amid the fog of elections. (Representative paper title: “Causal Inference with Differential Measurement Error: Nonparametric Identification and Sensitivity Analysis.”)

For his dissertation, Strauss set out to run a randomized-control experiment measuring the effect of get-out-the-vote reminders sent by text message before the 2006 midterm elections. Most of the early get-out-the-vote experiments conducted by political scientists measured the average impact of a given approach across the whole population that received it. But Strauss knew from his work with Dean and Kerry that computerized voter lists had made it possible to segment voters based on their unique attributes. With co-author Allison Dale, Strauss layered that individual data into the experiment’s design to refine its insights into cause and effect. On average, their text-message reminders increased turnout among recipients by three points. But using voter data, they confirmed empirically what may have previously been mere instinct: The biggest impact was felt among digital natives, voters between ages 20 and 24.

Photo by Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images.

Strauss earned his doctorate and returned to politics, where experimenters at liberal institutions had begun toying with similar statistical methods. Unlike university researchers, they weren’t limited to nonpartisan mobilization exercises; they could also try to change a voter’s mind about who to support. And instead of merely looking at the demographic variables available in voter-registration records, partisan experimenters can also overlay the results of microtargeting models that sift through hundreds of data points to generate “support scores”—a percentage probability that an individual would back the Democratic candidate.

The people who first developed the microtargeting models used in persuasion had assumed, like the rest of us, that voters in the center are the most up for grabs. But in 2006, EMILY’s List ran a series of persuasion experiments that raised doubts about this assumption. The Democratic women’s group sent out mailers on behalf of female gubernatorial candidates in Michigan and Washington, then polled across the entire universe of recipients to gauge the impact of the messages.

The voters who’d been assessed as sitting closest to the middle of the road barely budged. In fact, there was significantly more movement among those who were projected to be leaning toward the Republican candidate than among those whose mid-range scores situated them evenly between the two poles. “Campaigns love to find out what segments of the population are their targets,” Strauss told me last summer in an interview for my book The Victory Lab. But that alone, he went on, was insufficient. “Targeting is all about finding people whose behavior will change and changing that behavior.” And it turned out that the people who’d scored close to 50 on the zero-to-100 spectrum of support weren’t the people whose behavior was most likely to change. Whatever those support scores were measuring, it wasn’t exactly susceptibility to persuasion.

Again working for Mellman, Strauss designed an experiment to test voters’ responsiveness to messages used by Harry Reid’s campaign as it prepared for a tough 2010 re-election to the Senate. Afterward, by identifying the attributes of voters who changed their opinions of Reid when presented with his primary campaign themes in so-called “trial heats,” Strauss was able to develop a “persuasion score” for all Nevadans, estimating an individual’s probability of being moved by that message. “Everybody has the probability of being the type of person that could be persuaded by this messaging,” Strauss explained. “So you want to give everyone a score, a probability of being persuaded, and also a probability of being unmoved and additionally a probability of being anti-persuaded—that they will counter-argue the message and actually move away from you.”

The Reid experiment, and a simultaneous test during Kentucky Congressman Ben Chandler’s re-election, reaffirmed the initial EMILY’s List finding: A campaign couldn’t just scoop up people who appeared to reside in the political center and assume they were all persuadable, an assumption now discredited in Analyst Institute circles as the “middle-partisan fallacy.” “It’s not always guaranteed that the people in the middle of a support score are the most persuadable,” Strauss said. “Some messages work really well to prevent defections on your side, so they would work best on people with high support scores. Some messages work best at promoting defection, so they work best on people with low support scores. And some messages do honestly work best in the middle, but you don’t know what kind of message you have ahead of time.”

Strauss began to look at why voters might be showing up with those middle scores but not moving. He thought of them as existing in three different categories. Some voters had simply remained relatively anonymous, with little data about them on file to push them toward one candidate or another, while others existed in demographic categories that did not contribute meaningfully to predictions about their politics. (One example Strauss uses is voters in their 30s, “an age range that neither leans Democrat nor Republican.”) In both of these cases, the middle-range scores gave a misleading indication that a voter was persuadable. “I have to always remind people that 50 means we don’t know, not that someone is evenly divided,” says one Democratic state-party data manager.

Photo by John Moore/Getty Images

There was a third case, though, in which there could be lots of data available about an individual voter that effectively cancels itself out. These situation resembled the predicament that political scientists have long defined as cross-pressure, where a voter’s choice is complicated by conflicting aspects of his or her identity—the African-American who’s also a Mormon, to take one example. In these cases, a mid-range score seems to quantify precisely the type of ambivalence that makes for a good persuasion target. “We certainly want to talk to voters who are cross-pressured,” Strauss has written.

The hunt for persuadable voters has taken Strauss to the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, whose staff he joined earlier this year after leaving Mellman’s firm. In June, the DCCC ran what Strauss called a “persuasion-microtargeting experiment,” to test Democratic messages on voters in the field. Experiments found pockets of voters who moved in their direction in response to particular appeals: After hearing the party’s message on Medicare, men over the age of 65 increased their support for a generic Democratic congressional candidate three points more than the broader population. The DCCC could build a profile of voters whose opinions it could change, even if the data about them didn’t portray them as perfect centrists.

Only through such experiments that try to push voters and wait to see which ones moved can targeters know which voters were actually persuadable, and to what messages. At the moment it appears that only one side has embraced experiments for campaign research, and in his job as the DCCC’s data and targeting director, Strauss is in a position to institutionalize within his party’s campaign culture the skepticism he has developed about traditional targeting logic. “I actually think this is a competitive advantage we have right now over the Republicans,” Strauss, who would not comment for this piece, said last summer. “That competitive advantage might not last, but I think we have a competitive advantage over them.”

***

Republican operatives around the country have noted with a mixture of curiosity and anxiety that nearby mailboxes are less crowded with mailers making the case for Obama than they were four years ago. This may be the result of a strategic imperative: In many states, Obama has a clearer path to victory than Romney solely by mobilizing existing supporters than by finding new ones. But it could also reflect the fact Obama’s strategists do not think they have to rely, as have most campaigns over the last generation, solely on the mail for their targeted efforts to win over voters.

Earlier this year, Obama put his volunteers’ ability to do that to the test. The campaign administered an experiment in several states in which phone-bank volunteers were given a script with a few talking points and broad instructions to open up a conversation with a potential voter. Before and after these interactions, a professional call center surveyed the targeted voters to identify which candidate they supported, and campaign analysts set to work developing a statistical portrait of those who moved in Obama’s direction after talking with a volunteer.

The result of that analysis is the campaign’s so-called persuasion model, which generates a score predicting, from zero to 10, the likelihood that a voter can be pushed in Obama’s direction. (The score also integrates a voter’s likelihood of casting a ballot altogether, so that field organizers focus the attention on those with the best chances of turning out.) A zero designates a voter likely to be repelled by the interaction, and actually pushed toward Romney or a third-party candidate; a one projects a minimal possibility of persuasion; a nine someone who can be easily pushed.

Campaign strategists have traditionally been so fearful of triggering a backlash that they rarely entrust volunteers with persuasion efforts. When placed at a phone or given a clipboard to knock on doors, volunteers usually are given tasks that do not require them to discuss sensitive or complex topics—their role has typically just been asking voters who they support, and reminding those who declare their support to turn out.

(While in 2008 Obama encouraged volunteers to make the case for the Democratic candidate in their communities, the campaign never saw it as a replacement for their paid persuasion strategy. One adviser from that campaign mockingly describes the 2008 sensibility as “building this utopian society where people talk with their neighbors.” Obama’s strategists certainly didn’t let up in traditional channels, like television ads and direct mail, where they can deploy language and imagery delicately calibrated after polling and focus-group research.)

“Persuasion calls are a more difficult thing for a volunteer to do because it’s a lot easier to hang up on someone than slam a door in their face,” says Wisconsin Democratic Party chairman Mike Tate. “You’re not just asking someone who they’re going to vote for or reminding them to vote—you’re going to people who are undecided, who don’t want to hear from you, and are often sick of politics.”

Now, thanks to its experiments, the campaign feels confident enough in its ability to identify persuadable voters that it can direct well-trained volunteers to call them with pre-written scripts. (In an election year when so few voters are at all open-minded about the candidates, true persuasion targets are so dispersed that it is rarely efficient to send volunteers walking among their houses.) The messages are crafted for different kinds of persuadable voters. Obama’s persuasion message for certain female targets threatens a “return to an era when women didn’t have control over own health choices.” Analytics are transforming the role, and value, of volunteers.

Romney’s campaign, meanwhile, appears to be selecting targets largely through the same method used in George W. Bush’s 2004 campaign. After asking which candidate a respondent supports, the surveys that feed into Romney’s microtargeting models also plumb for a voter’s “anger points.” How angry does Obamacare make you? What about growing deficits? With this data, Romney’s targeters are able to model the likelihood that a voter will respond emotionally to one of its appeals—and if that person appears in the middle range between predicted support for Obama and Romney, the campaign will send a sequence of mail pieces on a related theme, like economics or social issues. While Republicans add modest pro-Romney “advocacy” messages at the top of the scripts used at their Victory Center phone banks to identify potential supporters, they are relying on paid channels, not volunteers, to deliver persuasion messages.

This summer, the Romney campaign appears to have concluded Sarah Yancey was persuadable, and then assigned her into the issue bucket she fit best. In this case, she got assigned “the economy,” which explains the series of at least 10 mailers she received about coal, welfare, deficits, and spending. “All my mail from Romney about coal seems completely irrelevant to me,” she says.

In August, Sarah moved out of her parents’ house and into an apartment complex in another Virginia county two hours to the northeast. She registered to vote there, and at the new address started receiving mail from Obama’s campaign for the first time. It was less demographically jarring: One piece dealt with birth control, another with rising education costs. Obama’s analysts clearly now saw her as one of those middle-of-the-roaders who was a good target for persuasion, and also probably concluded they had no other way to reach her besides through the mail: Unlike her parents, she has no landline at her current address, so if they had been trying to reach her by phone, or had planned to, that option was no longer available. (Obama’s campaign has experimented with individual “callability” scores, refining the ability to predict how easy it would be to reach a given voter by phone.) Sarah says she has been planning to vote for Obama all year, and has never revisited that choice, though the campaign’s contact has successfully warded off any ambivalence. “The mailings I’ve received have made me more enthusiastic about my choice,” she says. The campaign hadn’t converted a new vote, but it successfully shored up an existing one.

Targeting is by its nature a game of imperfect predictions. Campaigns want to sort voters into different buckets so that they can design the most meaningful possible interactions possible based on incomplete, inconsistent, and uneven data. Targeters know they will always miss their marks, so their goal is to intelligently assess that risk in a way that allows them to minimize the costs (economic and electoral) of misfiring. Democrats have gotten smarter about acknowledging the limitations of solely directing persuasion efforts to the middle part of the spectrum, and are ending this election season with a major advantage in managing risk as they set out to engage the few votes whose minds can still be won. They are also able to confidently extend their hunt for persuadable voters outside the unexpectedly perilous middle terrain and to calculate who among them will be responsive to particular messages (like on Medicare) or specific modes of contact (a call from a volunteer).

Yet while Democrats may be using experiments to expand their universe of persuadable voters, they acknowledge that they thus far lack the ability to exclude those, like Sarah, who may not have ever been truly persuadable in the first place. Democratic analyst Tom Bonier says one of the post-election priorities of his Clarity Campaign Labs will be research and testing to “differentiate the mid-partisans who are there due to lack of information versus those who are there due to conflicting or counter-pressured data.” Already, according to Bonier, the new firm has started randomly assigning treatment and control messages to its surveys in the hopes of “beginning to paint a picture of potential movers to tease out the mid-partisans.”

For its part, the Romney campaign has still not given up on persuading Sarah, but appears to have failed a more basic test of tracking voter behavior. The campaign is still sending her mail at an address where she no longer lives or votes.