On Wednesday’s Trumpcast, Jacob Weisberg spoke to New Yorker staff writer Patrick Radden Keefe, whose article “Carl Icahn’s Failed Raid on Washington” documents how the billionaire special adviser to President Donald Trump tried to get an obscure Environmental Protection Agency rule changed to benefit his bottom line—and how he might not be alone in this “corporate raid on Washington.” This transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Jacob Weisberg: This was a fantastic piece that got results. Carl Icahn has been fired, or as he says, resigned.

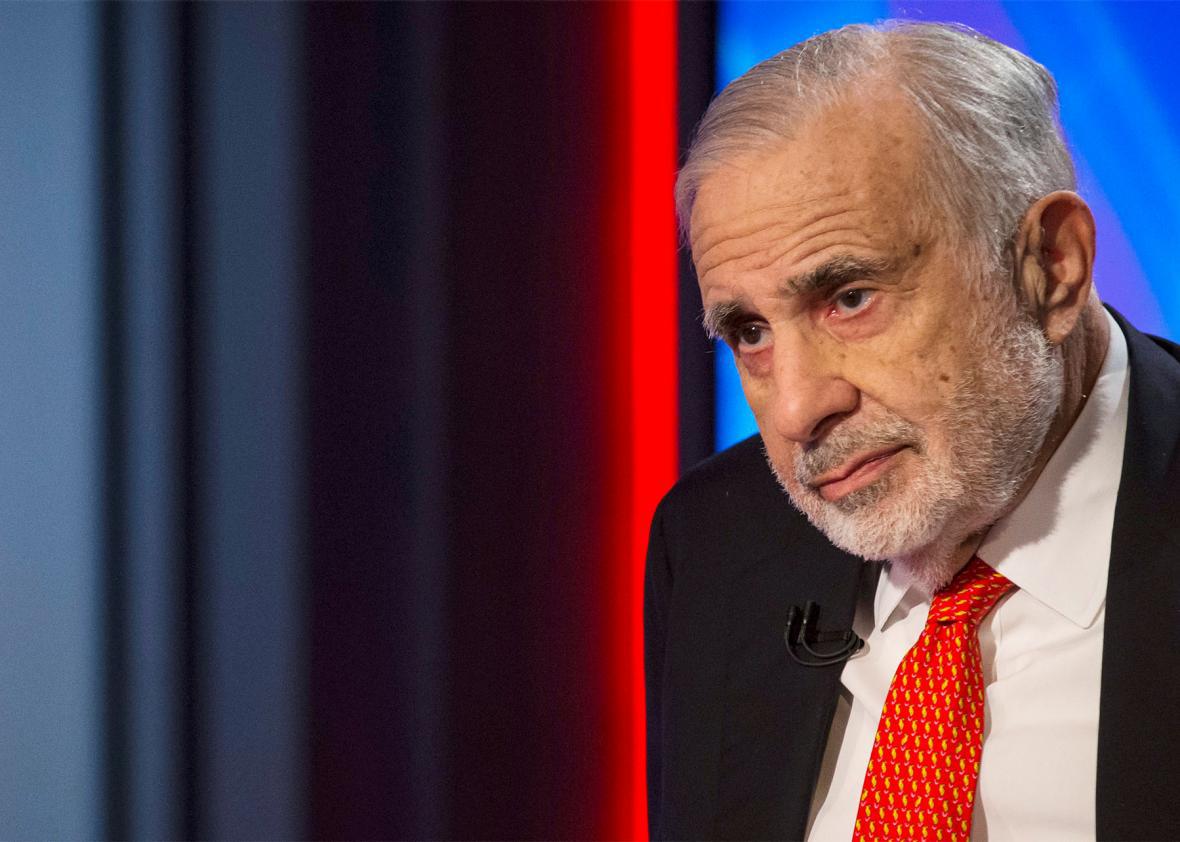

Patrick Radden Keefe: Carl Icahn came to prominence as one of the original corporate raiders back in the ’80s—a guy who did hostile takeovers. At the time, he was this very rich guy who was said to be one of inspirations for the Gordon Gekko character in Wall Street, but he was also somewhat reviled because he came in and took over corporations. The corporations themselves often didn’t want him to. He was a bit of a pariah. But these days, he’s just one of the richest guys in the country; Forbes says he’s worth about $17 billion. He’s a fixture on CNBC and has been embraced by Wall Street, belatedly.

He was a Wall Street person who supported Trump from early on, right?

He was of the few Wall Street people who came out early on and really bet on Trump. At a time when Goldman Sachs folks were saying nasty things about Trump and Trump was saying nasty things about Goldman Sachs, Icahn embraced Trump and said, “Look I’m gonna stand by this guy. I’ve known him for decades.”

The big issue for Icahn was deregulation. He said, “I think Trump’s gonna go in there and cut regulations back.” On that basis, he threw his weight behind Trump.

Let’s get to the grotesque corruption, or I guess may aborted corruption, at the heart of this story, which has to do with an effort to deregulation. I don’t even know if you call it deregulation but changes in regulation that would benefit Icahn personally and materially. What did he try to do?

Icahn is the dominant stockholder in a Texas-based oil refiner called CVR. Under the Renewable Fuel Standard—a law passed under George W. Bush that tries to incentivize the blending of ethanol and other biofuels into gasoline—the refiner that Icahn owns was obliged to buy these renewable fuel credits. They either had to blend the ethanol or buy these credits. At the time when he purchased his stake in 2012 in the refiner, those credits cost very little—about a nickel each. But the price had gone up and up and up for the credits. By the summer of 2016, CVR was paying about $200 million a year to purchase these credits. This drove Icahn berserk.

Long before Trump seemed like a legitimate candidate for the White House, Icahn was out in public saying the Environmental Protection Agency, which regulates this system with the credits, needs to change what it calls the point of obligation. So basically merchant refineries should not be the ones that have to purchase these credits or blend the ethanol. You need to shift that point of obligation closer to the gas pump.

It was this pretty obscure rule that he became totally obsessed with. In talking to people who know him, this is typical of Icahn. He’s hugely wealthy. He has interests all over the place. But if there’s one small thing that begins to drive him crazy, he’ll just obsess over it. He became obsessed over this particular rule.

To be clear, there’s no kind of intrinsic right or wrong here, because Iowa has outsized political power. We have corn-based ethanol in our gasoline. Some people argue that it’s been environmentally beneficial. Some people argue that it’s been a massive boondoggle. I’m a little bit on the massive boondoggle side. But this isn’t pro-environment versus anti-environment. This is the interests of certain refiners versus the oil companies, or certain refiners versus other refiners, right?

You would be hard-pressed to find someone who would tell you it’s working really well. There are all kinds of critics who have, I think, legitimate basis for criticizing the way in which the standard operates today.

It was important for me in writing this article to be somewhat agnostic on the merits of the actual argument that Icahn was making because to me the argument is not the point. It’s actually a story about government process.

I think that’s exactly right. What Icahn did is just so clearly corrupt. He essentially started saying to people, “Look, Trump’s gonna sign an executive order changing this regulation so that it’s no longer the responsibility of these oil refiners to get these credits.” Sounds like he sent Trump an executive order that he wrote in a half-assed, not-knowing-how-to-write-an-executive-order way, for Trump to sign.

The price of these credits, which trade very nontransparently, shot down because he created the impression that Trump was about to do this. He was then able to buy the credits he needed on the cheap.

That more or less tracks with what I was able to document.

Part of what’s fascinating about this story is that it’s weeks into the administration—you’re not even talking about the first 100 days here. You have this really obscure rule EPA rule that nobody’s ever heard of, but it’s a major issue for this one guy, Carl Icahn, whom Trump had appointed to this sort of novel position. His title was special adviser to the president for regulatory affairs, or something to that effect.

But it was unusual, as the appointments go, because he didn’t need to disclose anything. He didn’t need to give up any of his assets. Pretty much the first thing he does in that capacity is to urge Trump to make this change that will directly benefit him. We know this in part because he’d been really aggressively, kind of publicly lobbying for this change in the month leading up to the election. As he’s doing this, he’s also meeting with folks in industry and saying, “I’ve talked to the president. It looks like he’s gonna make this change.”

I interviewed Bob Dinneen, who runs one of the leading trade groups for ethanol and ends up negotiating with Icahn. Initially he completely changed the stance of his organization, which had always opposed the idea that you would shift the point of obligation. He goes into these meetings with Icahn, and he comes out and says, “We’ve done an about-face. We’re gonna make this change.” When he was asked about this by the press, he said, “Oh, you know, a Trump administration official told me this change was coming.” Then, certainly with me, he said, “But the only Trump administration official I ever talked to was Carl Icahn.”

It’s a conflict of interest. It looks like insider trading. Why isn’t Carl Icahn being indicted and prosecuted right now?

I think there are a bunch of answers to that. In talking with Icahn and in talking with his lawyer, they make a bunch of different arguments. They claim that he never had an official role, which I think is kind of nonsense. There was a press release put out by the transition team with quotes from Trump saying he’s going come in, he’s going to have this title.

There are questions in terms of whether it would be an insider trading case—the fact that he was essentially shorting the value of these credits. The credits are a commodity, so it wouldn’t be a securities case. But there could still certainly be a fraud case there. I talked to lawyers who thought that there would be.

But the other thing is there’s a federal statute that says that if you are an executive branch employee other than the president and the vice president, you cannot give advice on a matter in which you have a personal financial interest.

It was illegal to manipulate commodities markets before anybody was being prosecuted for insider trading in the stock market.

Exactly. When you look at when exactly the value dropped and you map that with the news of these conversations that Icahn was having, there’s no way not to conclude that he was driving the price down.

Patrick, I’m more outraged than you are about this. This guy deserves a fair trial like everybody, but he should be in jail.

This was a frustration for me as a reporter: I don’t have subpoena power. So, in terms of the trades, it would be really interesting to find out when and how those were authorized and how again that maps onto the timeline and the conversations he was having with folks in the administration.

Is the Trump Justice Department going to investigate? I don’t think so. You had a whole bunch of Democratic senators who have written a whole string of outraged letters about Icahn to anyone whom they can think of. They’re not really getting any traction. Within a week before my piece came out, the White House told me, “Hey, you know what? Icahn’s no longer working for us in any capacity.” Then hours before my piece posted, Icahn announced himself that he was stepping down.

This was the week that all his other business advisers were resigning from their commissions and appointments in the councils. But his didn’t have anything to do with Charlottesville. It was because of your story.

Exactly. It’s primarily the financial press that covers this guy. It is amazing to me the degree to which they will stenographically take down whatever he says in terms of him explaining it.

After he resigned, there was this whole round of stories in which if you just read the headlines, you would think, Here’s another guy who’s been pushed to a crisis of conscience by the awful events in Charlottesville. In fact, if you read Icahn’s statement, there’s none of that at all. It didn’t in any way inform his motivation.

We need another special prosecutor for this case, right?

I think that’s probably right. As I was working on the piece, I heard a number of rumors from different people suggesting that Eric Schneiderman, the attorney general in New York, might be looking into this. I couldn’t get any confirmation of that, but I did talk to Eliot Spitzer, who had held that job in the past. He said, “Oh yeah, if this came across my desk and I was sitting in my old office, we would absolutely take a hard look at this.”

I think we have tended to concentrate on the ways in which the president is enriching himself and his family by using the White House and the presidency. But what tends to get overlooked is that there are a lot of other people doing it too, and Trump’s letting this happen. Carl Icahn presumably is not the only crony of Trump’s who thinks he might be able to pocket $100 million by basically corrupting the regulatory or deregulatory process.

It’s amazing to me both in his conversation and in his resignation letter, Icahn thinks this is exculpatory. He says, “The only issue I ever told Trump what to do about was this one, where I had some skin in the game.” He comes out and essentially says, “Outside the four corners of my own self-interest, I didn’t have any regulatory ideas that I would bring to the president.”

The way this whole piece got started for me was a conversation in February I had with someone. I was meeting with a source—a financier—about a different story. He mentioned Icahn, whom he knew. What he said to me at the time was, “There’s this whole circle of people around Trump who essentially are regarding his presidency—it’s like a corporate raid on Washington. They’re gonna go in and get what they can get.”

That was the theme that came up again and again, talking both to finance folks who know these people in New York and to government folks in Washington, who I think feel a little bit blindsided by this mentality—even people in the Trump administration.

Mike Catanzaro, who works for the National Economic Council, ended up putting the brakes on this Icahn executive order. I talked to a couple of people whom Catanzaro has spoken to, so they were characterizing for me conversations with him. One of them said, “Mike essentially was forced to say, ‘Hey, look, the government is not a vending machine for the president’s friends.’ ” This guy said, “Unfortunately not everybody in this administration takes that view. Some people really do seem to think that it is there to be pillaged.”

Why does Icahn want to risk going to jail to make $100 more million?

I don’t know that he fully appreciated the risks going in. It’s strange for a guy who’s so sophisticated that he was actually a little bit naïve about how easy or hard it would be to engineer this kind of thing in Washington, to change a regulation.

I think there’s something compulsive about Icahn. He has a really interesting backstory and issues from his own childhood—I’m not playing armchair psychologist here because he talks about them relentlessly—where there’s clearly some hole he’s trying to fill. Someone asked him, “You’re never going to be able to spend all the money you’ve got. Why keep making it?” What he said was, “It’s a way of keeping score.” If that’s your mindset, I wonder if it’s possible to stop.

Every line in the movie Wall Street is like something Carl Icahn actually said.

Reportedly, the line “if you want a friend, get a dog” came after Oliver Stone, while researching the film, went and met with Carl Icahn.