In May 2016, Maranda Lynn O’Donnell, a waitress and mother of a 4-year-old girl in Harris County, Texas, was arrested for allegedly driving with a suspended license, a misdemeanor offense. She did not have $2,500 to bail herself out, so she was locked up in jail for two days, unable to go home to her daughter. The same day, Robert Ford was arrested for allegedly stealing cosmetics worth $100, also a misdemeanor. He too was sent to the Harris County jail, where he remained for five days, unable to shell out $5,000 for bail. The day after that, Loetha McGruder—who was pregnant with two children at home, including one with Down syndrome—was arrested and detained for falsely identifying herself to an officer. With bail set at $5,000, she remained in jail for four days.

All three of the defendants are plaintiffs in a class-action lawsuit that aims to overhaul the bail system in Harris County, Texas, home of the nation’s third-biggest county jail system. The suit, filed in May 2016 in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas, calls bail setting in the state’s largest county a “wealth-based detention scheme” that punishes defendants accused of misdemeanors for being poor and encourages them to plead guilty to avoid jail time.

In April, Chief Judge Lee H. Rosenthal decided in their favor, writing that it was unconstitutional to jail people because they can’t afford bail. Rosenthal ruled that Harris County would have to ask defendants about their financial backgrounds and release them if they didn’t have enough money to pay their bonds. The county challenged the decision, and the case now sits with the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, known as one of the most conservative courts in the country. In light of this setback, the plaintiffs and their lawyers have been searching for allies to support their case. They now have a powerful group on their side: religious leaders that say they have a duty to fight for the poor.

In August, the Texas Catholic Conference of Bishops, Texas Baptists Christian Life Commission, and Harris County clergy filed an amicus brief in support of the plaintiffs. While the legal fight hinges on the constitutionality of imposing cash bail on defendants who can’t afford it, the faith coalition argues that the system is simply unethical, posing steep “moral” and “human” costs that deserve public scrutiny. It cites a Houston Chronicle investigation of 55 jail deaths that occurred between 2009 and 2015 in Harris County, many of which might have been prevented if prisoners had access to adequate health care. Instead, people were deprived of basic medical attention and died from treatable diseases, such as diabetes and tuberculosis. Detainees also face the constant threat of assault. “Justice that is blind to these dangers and that indiscriminately forces poor defendants to pay for their physical liberty is no justice at all,” the brief says.

The faith coalition also argues that Harris County’s bail system exacerbates poverty by threatening defendants’ job security and causing them to lose what little income they have. This can destroy families: Relatives, including children, who rely on that income are put in jeopardy, often unable to pay for rent or other necessities. In some instances, kids have been removed from their homes and placed in foster care due to financial strife. Likewise, elderly relatives who depend on family members to provide for them suffer when their caretakers are trapped behind bars.

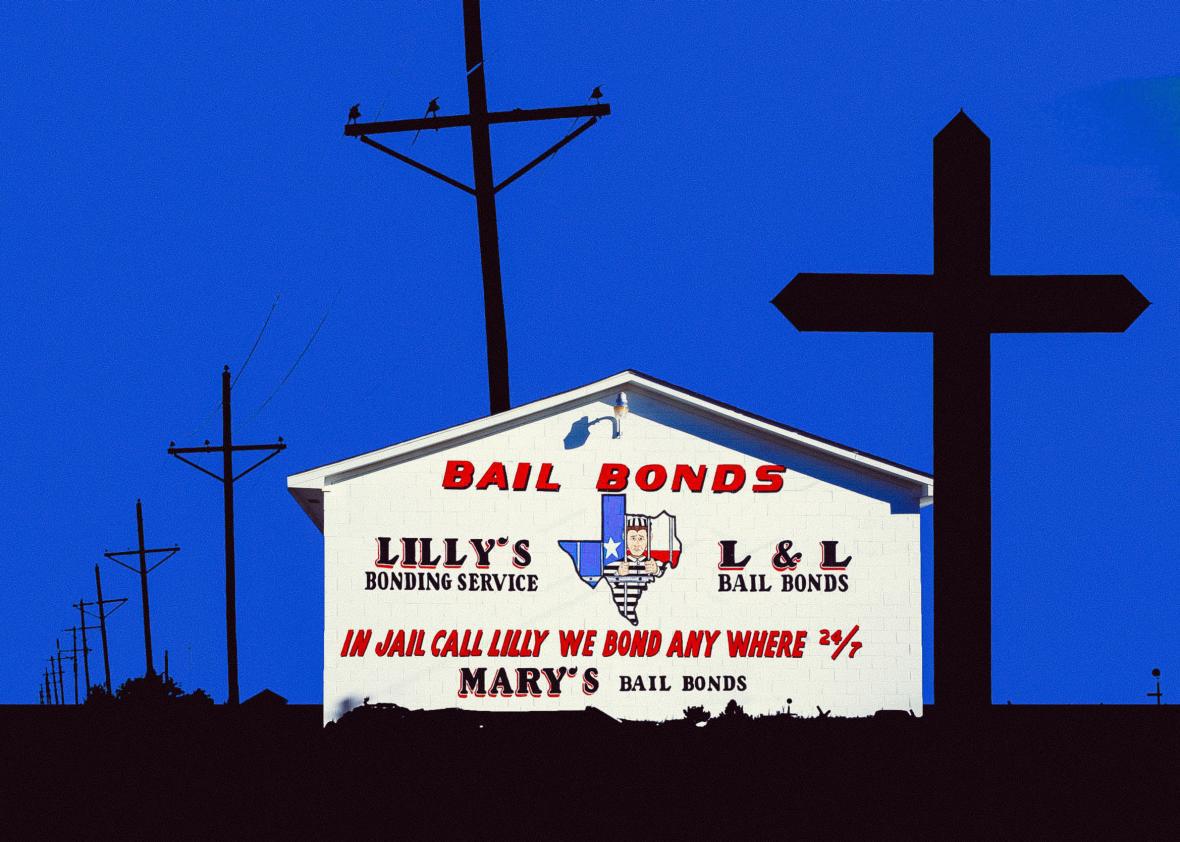

Jordan Corona

Representatives of the faith groups say they joined the reform movement because bail stands in opposition to basic religious teachings. “It really comes down to our biblical mandate to care for the poor and to provide the poor with justice,” said Kathryn Freeman, director of public policy for the Baptists’ Christian Life Commission. Indeed, faith leaders in at least two other states have also taken up bail reform in partnership with criminal and racial justice organizations. Before legislators in New Jersey passed a law in 2016 to drastically reduce the number of people who can be held on bail, more than 35 pastors, priests, and rabbis submitted a joint statement that criticized the “warehousing” of poor people in the state. Working alongside the Drug Policy Alliance, an organization that strives to end overzealous drug enforcement, clergy members also argued that locking people up without accounting for their ability to pay or the threat they posed to society was “immoral and dangerous.” (The Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the group founded by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., opposed bail reform that same year. Standing in solidarity with members of the bail bond industry, SCLC president and CEO Charles Steele Jr., argued that proposed reforms would still trap poor people of color in the criminal justice system.)

In California, where 62 percent of the jail population is made up of pretrial detainees unable to post bail, faith groups are involved in a grassroots campaign to mobilize voters and pressure state representatives to overhaul the system. In June, a bill to eliminate set bail amounts and pivot to a “pretrial risk assessment” plan failed in the California State Assembly due to pushback from the bail industry, although a sister bill did pass in the state Senate. Now, instead of sending the legislation to the assembly, authors of both bills are joining forces with Gov. Jerry Brown and Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye “to ensure the final plan is pragmatic, workable and enduring.” Bail reform advocates consider this a major victory and a result of their collaboration. “We’ve really pushed this from a small siloed issue into the greater consciousness,” said Ash Lynette, an organizer for Bend the Arc, a Jewish organization that promotes social change.

In Harris County, poor defendants not only have the support of religious advocates and criminal defense attorneys, but also law enforcement officials, judges, conservative think tanks, and national lawyers’ associations. There is a growing consensus among these groups that bail is outdated, costly, and antithetical to the precepts of the U.S. Constitution. “To hinge extended detention on a defendant’s empty pocketbook fails as a matter of compassion, of common sense, of public purpose, and of basic morality,” the religious leaders’ brief says. “This then is the charge across faiths: to denounce this bail system, to urge an end to the primacy of wealth over justice, and to spare individuals, families, and communities the harms that inexorably follow.”