When a U.S. district judge found Joe Arpaio guilty of criminal contempt of court in July, the conviction came as an unusual and hard-fought win for the grass-roots organizers and civil rights attorneys who have tried for years to hold the infamous former Arizona sheriff accountable. That victory was short-lived, as Friday’s pardon from President Donald Trump let Arpaio off the hook. Backlash to the pardon continues to grow as outraged onlookers accuse Trump of endorsing the illegal, discriminatory, and brutal actions of the limelight-loving lawman who once declared that comparisons between his department and the Ku Klux Klan were “an honor.”

Arpaio’s inhumanely hot “tent city” jail, racial profiling of Latinos, and enforcement of a pink underwear requirement for Maricopa County detainees were typically described as shocking outliers. Yet Arpaio’s tactics, while outrageous, aren’t as anomalous as we’d like to think they are. In counties across the United States, elected sheriffs oversee their communities and jails using variations on the same methods. The difference is that they typically get less press coverage and that the courts rarely hold them accountable for their actions.

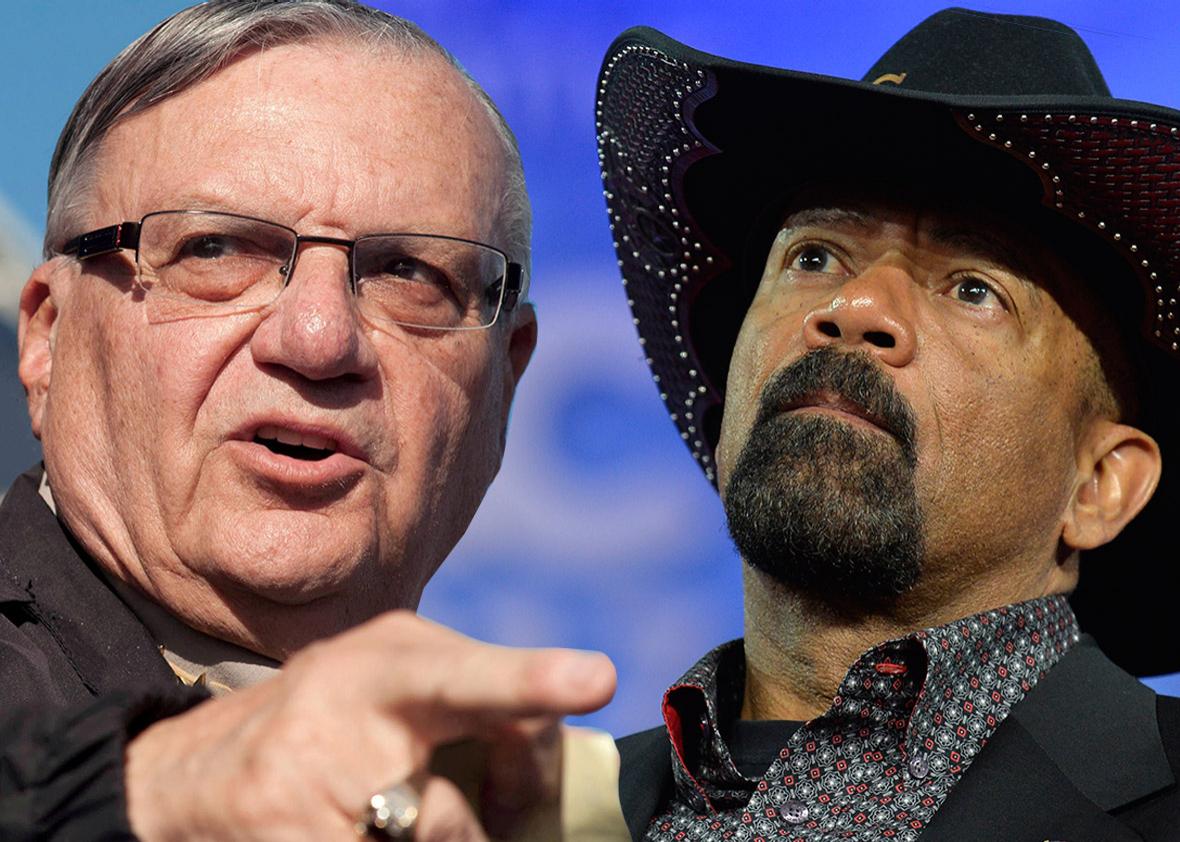

The foremost example of an Arpaio-like figure is David Clarke. The Trump-endorsed author and sheriff of Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, runs a jail system rife with abuse and fatalities, believes police brutality ended in the 1960s, and considers Black Lives Matter a terrorist movement. (When it comes to his disdain for Black Lives Matter, Clarke has an ideological companion in Gwinnett County, Georgia: Sheriff Butch Conway. Following the shooting of Michael Brown by Ferguson, Missouri, police officer Darren Wilson in 2015, an irate Conway issued a statement calling protesters “domestic terrorists” and insinuating that Black Lives Matter is a hate group.)

Like Arpaio, Clarke is vocally anti-immigrant, a stance he reiterated as jurisdictions around the country scrambled to establish or reaffirm protections for immigrants following Trump’s election. His desire for the county to join the Department of Homeland Security’s expanded 287(g) program, which essentially deputizes local law enforcement officers to act as federal immigration agents, caused a major clash with Milwaukee residents. After the county’s board of supervisors passed a resolution giving the municipality sanctuary status in January, Clarke lashed out on Facebook. “Nobody is going to limit my ability to work to prevent this reckless, shortsighted action of moving Milwaukee County into the status of a sanctuary anything,” he wrote. (In Bristol County, Massachusetts, Sheriff Thomas Hodgson has suggested that the leaders of sanctuary cities be arrested and has volunteered inmates from his county to help build Trump’s contested wall between Mexico and the U.S.)

It was Arpaio’s participation in the 287(g) program that led to his criminal conviction. The Department of Justice found that, under the auspices of the program, his deputies had “engaged in a widespread pattern or practice of law enforcement and jail activities that discriminated against Latinos.”

In California, Orange County Sheriff Sandra Hutchens announced she would not seek re-election in June after a series of allegedly Arpaio-esque actions. Under Hutchens’ watch, her department and the county’s district attorney’s office attracted both state and federal investigations. The inquests followed years of alleged misuse of jailhouse informants by both prosecutors and Hutchens’ deputies, who reportedly failed to turn over evidence in a high-profile murder case. After years of denying the informant program existed, Hutchens publicly acknowledged the misuse occurred, but chalked it up to a few bad apples in her department rather than a systemic problem.

A separate two-year investigation by the American Civil Liberties Union into county jails overseen by Hutchens reported the abuse of mentally ill detainees, unsanitary living conditions, a lack of medical care, and a culture of violence. The organization called for Hutchens’ resignation, citing her neglect of the “violence and squalid conditions.”

In Iberia Parish, Louisiana, 10 of Sheriff Louis Ackal’s deputies admitted to participating in brutality against inmates, and seven were sentenced. The abusive tactics used by the department, which were uncovered during a years-long federal probe, are staggeringly ugly. Deputies admitted to drunkenly beating young black inmates out of boredom; another forced a baton down a detainee’s throat and told him to “suck it.” Numerous deputies testified against Ackal, alleging the sheriff sanctioned and sometimes supervised violence against inmates. Nevertheless, a jury acquitted Ackal himself of all charges in November after the sheriff stood accused of encouraging his deputies to assault inmates and destroy evidence.

Ackal’s deputies have also drawn scrutiny for their actions while patrolling the streets. It was the Iberia Parish Sheriff’s Department that in 2014 told reporters that Victor White III, a 22-year-old black man, somehow managed to shoot himself to death in the back of a deputy’s car while handcuffed. (The shooting was ruled a suicide by a coroner.) More than 30 civil suits have been filed against the department since Ackal took office in 2008. He successfully ran on a reform platform promising to clean up the “terrible mess” of the jail system.

While Ackal allegedly took a hands-on approach to the mistreatment in his jails, other sheriffs have drawn criticism for their neglect. In Garfield County, Oklahoma, Sheriff Jerry Niles was indicted in July along with five jail employees following the death of 58-year-old Anthony Huff, who died on their watch in 2016 after allegedly being strapped to a chair for more than 48 hours and being denied medical care, food, or water. Niles maintains his innocence but suspended himself with pay.

This handful of examples includes a number of instances in which a sheriff was investigated. But investigations like these, much less guilty verdicts like Arpaio’s, are atypical. Many sheriffs play by the rules. Some don’t. In the aftermath of Trump’s pardon of Arpaio, we should recognize that he isn’t a total aberration. In too many jurisdictions, Arpaio-like behavior is all too normal.