Prosecutors in Wake County, North Carolina, have sought the death penalty in eight cases over the past decade.* Each time, jurors have rejected the sentence, most recently in March. The most recent time Wake County jurors imposed a death sentence was a decade ago. “At some point, we have to step back and say, ‘Has the community sent us a message on that?’ ” Freeman told reporters in February.

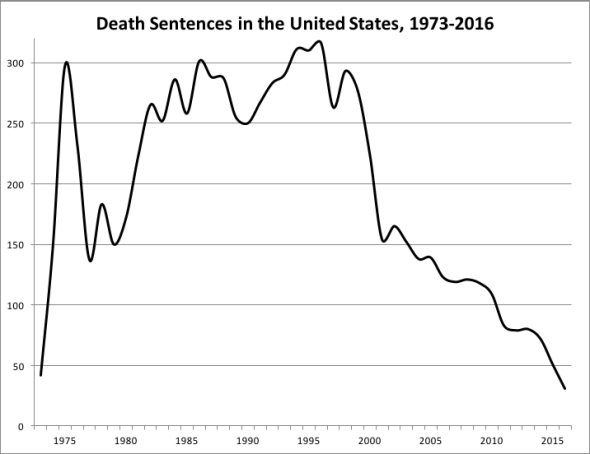

Capital punishment has now been outlawed in 19 states. In the places where it remains legal, jurors are increasingly reluctant to impose it. Just 30 people were sentenced to death in the United States last year, and only 27 counties out of more than 3,000 nationwide sent anyone to death row. In the mid-1990s, by contrast, more than 300 people were sentenced to death, with capital punishment being undertaken in as many as 200 counties each year.

Brandon L. Garrett

Jurors have even started to reject the death penalty in Texas, which has sentenced more people to death than any other state in modern times. Texas prosecutors are seeking the death penalty less often, and when they do, they’re frequently failing to persuade juries to impose it. In 15 capital trials in the state since 2015, just eight have resulted in death sentences.

So, what has changed the minds of jurors? It’s not that they’re morally opposed to the death penalty. In fact, jurors who object on principle can be disqualified from serving in capital trials. These are people who are open to imposing the ultimate punishment but decide to reject it after hearing a convicted murderer’s life story, including evidence of mental health issues, childhood abuse, and other mitigating circumstances.

Take the case of James Holmes, who was convicted of 24 counts of capital murder for opening fire in a theater in Aurora, Colorado, in 2012. After a lengthy trial in which defense attorneys presented detailed evidence about Holmes’ mental health problems, jurors chose a life sentence in 2015. Or consider the less well-known case of Russell Brown, who was found guilty of the capital murder of a state trooper in Virginia. In August 2016, the jury rejected a death sentence after experts testified that Brown was insane.

Another reason for the decline in death sentences is that murders have steadily declined across the country, beginning in the mid-’90s. (There has, however, been a recent spike in the murder rate in certain large cities.) When my co-authors and I analyzed death sentencing data by county from 1990 through 2016, we found that a drop in the murder rate was strongly associated with the decline in death sentencing.

But death sentences have fallen far faster than murders. One reason may be the growth in adequately resourced defense lawyers. In general, states that have statewide offices to represent defendants at capital trials, as opposed to locally appointed lawyers, have experienced far greater declines in death sentencing. Those offices have the resources to hire experts who can present mental health evidence and explain the defendant’s social history.

Virginia created regional defense offices to handle death penalty cases in 2004. Defense lawyers began calling more witnesses, presenting more mental health evidence, and telling a more complete story about the defendant’s background at sentencing. Although death sentences in Virginia used to be routine, there now hasn’t been a single one in seven years.

Our research also shows there is a strong “muscle memory” effect in death sentencing. Counties that have issued a death sentence in the past are far more likely to obtain more. What explains this substantial effect? Prosecutors may get in the habit of seeking the death penalty, even when neighboring counties do not. Perhaps losing a capital trial can put a damper on that enthusiasm. Generally, once that muscle memory fades, counties do not get it back. Indeed, the counties that started out with the most death sentences have experienced the biggest declines over the past 15 years. For example, in Harris County, Texas, where in the mid-1990s prosecutors led the country by securing 15 or more death sentences per year, there were no death sentences at all in 2015 or 2016.

As the death penalty fades, jurors may become more and more skeptical of its utility. Last year, psychologists Daniel Krauss and Nicholas Scurich joined me in surveying nearly 500 people summoned for jury duty in Orange County, California, an area that regularly imposes death sentences. We found that one-third of jurors—a surprisingly high share in that fairly conservative county—would not qualify to serve on a capital jury because they opposed the death penalty on principle. About one-quarter—a separate group from the one-third of jurors described above—said they would not convict someone of capital murder if that meant the defendant would be executed. Most strikingly, two-thirds of all jurors we surveyed said the fact that there had not been an execution in California in a decade made them less likely to sentence a person to death.

Our sample included both liberal and conservative jurors, and it consisted of whites, blacks, and Latinos, demonstrating that concern about the death penalty is broad-based. The responses of these jurors reveal why the death penalty is already at the end of its rope, no matter what tough-on-crime officials say. In 2015, the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia wrote it would be undemocratic for the court to decide whether the Eighth Amendment forbids the modern practice of capital punishment—that the issue should be left “to the People to decide.” Well, the people are now speaking, and their message is coming through loud and clear to prosecutors like Lorrin Freeman: The death penalty’s time has come and gone.

*Correction, July 11, 2017: This piece originally misstated that Wake County prosecutor Lorrin Freeman has sought the death penalty in eight cases over the past decade. That is the total number of times all prosecutors in the county have pursued the death penalty in the last decade. (Return.)