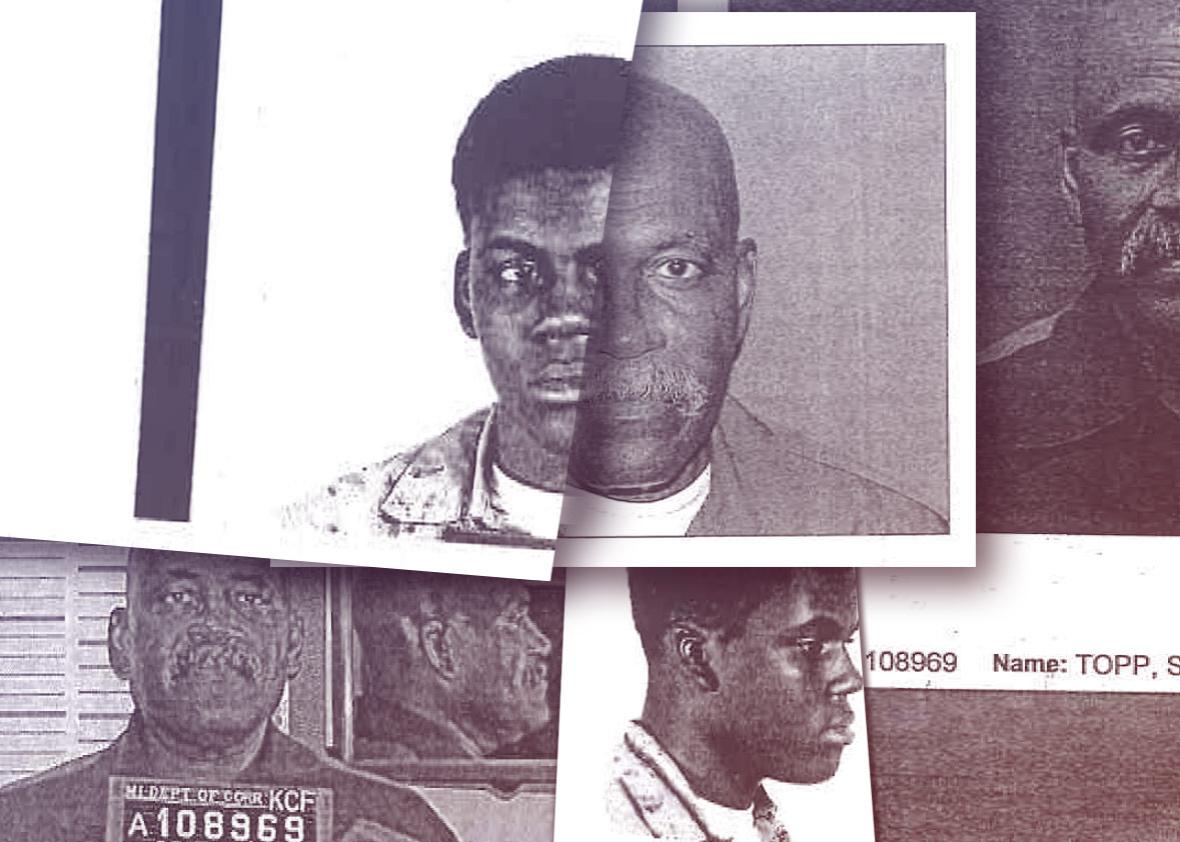

When Sheldry Topp was a child, his father whipped him regularly with an extension cord. At the age of 13, Topp was involuntarily committed to a state hospital and received electroshock therapy for an undefined mental illness. Four years later, in 1962, he ran away from the institution, broke into the home of an attorney in Oakland County, Michigan, and stabbed the man, who then died. Topp fled and was caught by the FBI. At the age of 17, he was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

At 72, Topp is the oldest person in Michigan serving a life-without-parole sentence for a crime he committed as a youth. Even though the Supreme Court has held that such sentences should be reserved for the “rarest of juvenile offenders” and 19 states plus the District of Columbia have eliminated them entirely, Topp is still in prison. The current county prosecutor, Jessica Cooper, wants to keep him there until he dies.

Topp told researchers from the Sentencing Project, a nonprofit research and advocacy group, that he never meant to kill anyone. “I only wanted to escape from the [state] hospital,” he said. “I spent most of my life from the age of about 13 in various juvenile [homes] and hospitals because of my attempts to escape from a father whom I feared so much that I constantly trembled in his presence.” Topp earned college credits in prison (before the program was cut) and received certificates in welding, plumbing, mechanics, and computer programming. But he may never get to use them.

Since the Supreme Court rulings in Miller v. Alabama in 2012 and Montgomery v. Louisiana in 2016, states have scrambled to figure out how to give those sentenced to life without parole as kids a “meaningful opportunity for release.” In the wake of those decisions, every state has been left to reassess its juvenile life-without-parole cases. Michigan has more than 350 cases requiring resentencing, the second-highest number in the nation after Pennsylvania.

While some states have opted to grant parole hearings to prisoners who’ve served a certain amount of time, others including Michigan have decided to hold resentencing hearings before a judge, who then determines whether each individual should get a parole-eligible sentence. This means prosecutors must comb through old files—some of which are missing—and attempt to reconstruct an individual’s mindset and history at the time of the crime. While the judge makes the ultimate decision, prosecutors are the ones who decide how to pursue each case. In many counties, prosecutors have declined to seek life without parole and allowed inmates to plead their cases to parole boards. But not in every county.

While the Supreme Court clearly mandated that life-without-parole sentences for youth should be rare, they aren’t in Oakland County, Michigan. Cooper, the county prosecutor, decided that 44 out of the 49 juvenile life-without-parole defendants in her district deserve to have those sentences kept intact.

When Cooper ran for re-election in 2016, she promised the harshest sentences for juvenile lifers, dubbing them “heinous” and “the worst of the worst.” She has consistently defended her support of life without parole in the press, arguing that youth is not an excuse for murder and pointing to defendants’ records in prison, some of which contain citations for misbehavior. In a phone conversation, she told me that in about half of the 49 cases, the defendants were older than 17, which in Michigan meant they were automatically charged as adults. The Oakland County sheriff, who supported Cooper’s campaign, compared those sent to prison as kids to “Hannibal Lecters.” Cooper, who was a judge before becoming a prosecutor, failed to recuse herself from three cases in which she herself had handed down the sentences. She assigned life-without-parole sentences in each of these cases from the bench and is seeking the same results as prosecutor.

Cooper’s office has granted the chance for release to just a handful of offenders. One of them is Thomas Anzures, who was resentenced to 30 to 60 years and released on parole this spring. Almost four decades ago, at the age of 17, he was convicted of shooting someone in the course of a robbery gone wrong—circumstances that seem similar to those in Topp’s case. Cooper told me Anzures had shown a great deal of growth in prison and was not the primary culprit in the crime.

As for Topp, Cooper explained to me that her decision was based on materials from his 1962 trial that she felt indicated he was “either a psychopath or a sociopath” and not redeemable. Cooper’s brief arguing for a life-without-parole sentence for Topp cites his “sociopathic” personality diagnosis, which an expert suggested prior to his sentencing. (This diagnosis is no longer in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.) One assistant prosecutor feebly defended the assertion, saying, “There’s just a nagging feeling in me that … there’s something that could snap in this individual again.”

Topp’s prison record does not support the argument that he is a danger to society. Reviews call him a “good worker” who is never absent and “gets along with others.” No one from the victim’s family has opposed Topp’s attempts to seek commutation. He has been housed in minimum security—meant for only the most well-behaved of inmates—and has never tried to run away. A majority of the parole board has also recommended Topp’s release on two occasions.

Topp’s situation is particularly complicated because, according to a recent court filing, substantial portions of the original case file were destroyed after the trial. Records indicate that Topp requested a copy of the file after his conviction but was denied because he could not afford to pay for the copies. Now those records, including the original psychological report, are gone. His current lawyer argues that the sentencing hearing cannot proceed without the transcripts and that Topp should therefore automatically be eligible for parole. This would not mean an immediate release for Topp, but would at least give him the chance for freedom before he dies.

Prosecutors like Cooper have argued that they are acting in the best interests of crime victims, who relied upon a promise that some defendants would be in prison forever. But in cases like Topp’s, so much time has passed that this argument no longer carries much weight. More and more states are outlawing juvenile life without parole in growing recognition that it is cruel and unfair to treat young people as throwaways. Topp is just one of thousands of prisoners still suffering from prosecutors’ unwillingness to give those who committed crimes as children a second chance.