The city and county prosecutor’s website promises that the Honolulu Family Justice Center is a safe haven, a domestic violence shelter that “will help victims break away from their abusers, regain their self-esteem, attain job skills and make new lives for themselves.” What the website doesn’t mention is that victims can’t bring their children to the $6.2 million shelter, which opened in November. They also must turn over their cellphones and laptops, and they will be turned away unless they promise to testify against their abusers.

While Honolulu’s prosecutor-run “shelter” with extreme strings attached is unusual, its prosecution-first, victim-second approach to domestic violence cases isn’t. Across the country, domestic violence victims who turn to law enforcement for help can be punished if they later decide that a criminal justice response isn’t in their best interest.

Want to listen to this article out loud? Hear it on Slate Voice.

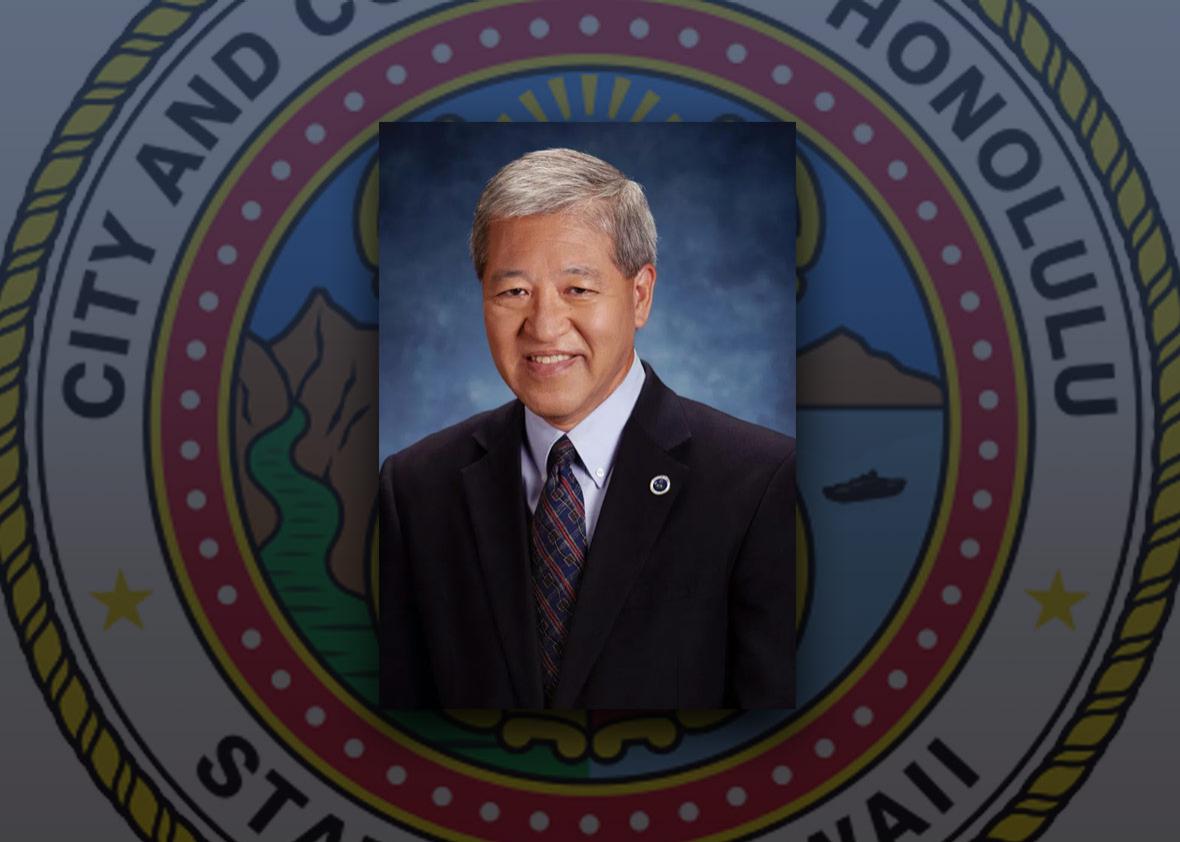

At the ribbon-cutting ceremony for the Family Justice Center, prosecutor Keith Kaneshiro stood at a podium, decked out in leis, and boasted that his office “did a lot of things to help victims of domestic violence, even when the victims did not know what’s good for them.” In the eight months it has been open, just four victims have opted to stay in the 20-bed facility, says Kaneshiro’s spokesman Chuck Parker. Of those four, two of their abusers pleaded guilty or pleaded to amended charges while the other two are awaiting trial. According to Parker, “some victims have declined the offer to go to the safe house because of the rules,” but he would not specify how many had turned down the opportunity to stay in the shelter.

This paternalistic approach to domestic violence victims stems from the foremost goal of prosecutors’ offices: winning convictions. “A prosecutor has a very different motive [than a domestic violence advocate],” said Ruth Glenn, executive director of the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. “Rightfully they should, because that’s their job.” Still, Glenn called Kaneshiro’s safe house a “bad model” and said she’d never heard of anything like it. “If a victim has gone to the shelter program to seek safety and then they have this [testimony requirement] hanging over their head, they may leave and go back to a riskier situation,” said Glenn.

Plenty of other jurisdictions have gone to extreme measures to get domestic violence victims to testify. Last year in Oregon, a woman who alleged she’d been sexually assaulted by a corrections officer was jailed on a material witness warrant to ensure she’d cooperate with authorities; she was held even though she told the judge she intended to testify. In Houston, Texas, former Harris County District Attorney Devon Anderson’s office jailed a rape victim for 28 days to force her to testify. “There were no apparent alternatives that would ensure both the victim’s safety and her appearance at trial,” said Anderson in a video statement defending the choice. In New Orleans, the practice of detaining domestic violence and sex crime victims to secure testimony is the status quo. “If I have to put a victim of a crime in jail, for eight days, in order to … keep the rapist off of the street, for a period of years and to prevent him from raping or harming someone else, I’m going to do that,” District Attorney Leon Cannizzaro said in April.

Ironically, the shift toward refusing to drop domestic violence or rape cases came in response to complaints from victims’ rights groups and community members in the 1970s that police and prosecutors were not taking domestic violence victims seriously. University of North Carolina law professor Deborah Weissman says the pendulum has now swung too far. “This has nothing to do with helping the victim,” says Weissman. “Taking these cases seriously shouldn’t mean “rip[ping] somebody away from their ability to make decisions.”

For prosecutors like Cannizzaro, jailing a victim who hasn’t committed a crime is a means to the end of securing a conviction, even if such a move denies that victim her liberty and disrespects her wishes. The perception that jail time is an unfortunate necessity fails to acknowledge the horrors endured by incarcerated people every day. The Houston case described above illustrates the inherent risks that come with incarceration. When that victim, who is bipolar, reached the witness stand, she reportedly suffered a mental breakdown, began crying, and ran into oncoming traffic in front of the Harris County Criminal Courthouse.

After the incident, she was jailed by Anderson’s office, which feared her breakdown would prevent her from testifying again. According to a lawsuit she has brought against Nick Socias, the assistant district attorney who obtained the warrant for her arrest, the victim was physically assaulted multiple times by other inmates. In December, Socias defended his decision to jail her, saying, “I did everything I could for this girl, and I did everything I could to make sure no one else would have to go in a hospital, get a rape kit, or end up dead in the street from this man.” After nearly a month in jail, the woman ultimately testified, and her rapist is now serving two life sentences. The suit against Socias is currently pending.

Honolulu’s Kaneshiro is no stranger to the practice of jailing victims: In 2011, he had a woman arrested at her graduation party to guarantee her testimony against an ex-boyfriend who’d allegedly abused her. Kaneshiro’s stop-at-nothing approach is part of his office’s “no-drop” policy for domestic violence cases. Even if a victim recants her complaint or changes her mind, Kaneshiro will still pursue the case against her wishes.

A proponent of stricter sentencing, Kaneshiro once urged the public to call or write to a judge who was handling a rape and murder case to encourage him to impose a harsher sentence. Prior to his current term in office, he made prison expansion his chief priority. During his second campaign, he boasted that his office’s stingy approach to plea bargaining had made the city safer. His intensely punitive approach hasn’t backfired with voters yet—this is his second term in office—but the Honolulu Family Justice Center is attracting criticism from local and national domestic violence experts and advocates.

“[Kaneshiro] doesn’t have any working collaborative relationships with domestic violence providers,” said Nanci Kreidman, CEO of Honolulu’s Domestic Violence Action Center. “We’ve been completely cut out of the conversation.”

Seven years ago, the city prosecutor’s office hired the domestic violence organization Alliance for HOPE International to develop a plan for an agency that would provide services to victims and their families. Casey Gwinn, who developed the Family Justice Center model in San Diego and has since helped to open roughly 50 similar shelters across the country, worked with the then–city attorney to plan the new center.

When Kaneshiro took office in 2011, he terminated the office’s contract with Gwinn’s organization and flipped the plan on its head. Gwinn later sent Kaneshiro’s office a cease-and-desist letter demanding it change the name of the shelter. “It sounded far more like a victim jail than a Family Justice Center,” says Gwinn. Kaneshiro ultimately changed its name to the “Honolulu Prosecutor’s Safe House” after receiving that cease-and-desist letter, though both names remain on his website.

“It’s a misuse of the power of the criminal justice system,” says Gwinn. “Prosecutors across America win these cases without victim testimony. Cases don’t get better when you jail your victim.”

Harris County District Attorney Kim Ogg, who beat Devon Anderson in the 2016 election, has promised never to jail a victim who doesn’t cooperate with her office. During her campaign for district attorney, Ogg told Houston TV station KPRC that jailing a victim on a material witness bond “is highly irregular and reserved for the worst of the worst witnesses, maybe gang cases,” noting that testimony could instead be ensured by “placing them in a hotel, you can place them with family, you can keep in contact.” Ogg also fired Socias, the ADA who’d jailed a rape victim.

Some prosecutors, including ones who consider themselves progressive, don’t agree with Ogg’s declaration that there should be a hard-and-fast rule against incarcerating victims. In Kennebec County, Maine, District Attorney Maeghan Maloney has twice had a domestic violence victim arrested to ensure testimony. In one instance, a victim was jailed overnight after she stopped responding to Maloney’s office. Maloney says the victim’s abuser had threatened to kill her, going so far as showing her a grave he’d dug for her in the woods. Although Maloney credits the victim’s testimony with helping her win a 10-year prison sentence, she says jailing a victim should “be a last resort always.”

“It’s not something I’m proud of by any means,” says Maloney. “I felt like it was the only choice I had to save her life. I hope I never have to do it again.”