When Nathan King was arrested in 2014 and detained in the Polk County Jail for trespassing, his family had no reason to believe his life was in danger. Police in Livingston, Texas, knew King suffered from bipolar disorder and had always treated the 37-year-old with dignity whenever they’d crossed paths in the past, his uncle Don Glenn recalls. Officers usually brought King to a mental health facility or dropped him off at a family member’s house. The sheriff had even taken him to McDonald’s. So, when King didn’t come home from jail right away, his family wasn’t particularly concerned; they believed law enforcement was taking care of King and chalked the situation up to administrative errors. That changed when a cousin locked up in the same jail told King’s mother her son’s health appeared to be deteriorating rapidly. Months later, in February 2015, King collapsed in jail and died from tuberculosis he’d contracted behind bars. His body was covered in bruises.

“I’m still trying to wrap my brain around how someone could walk by someone every day and see them getting sicker and sicker and not give them so much of, ‘Hey, let’s do something. Let’s get this guy checked out,’ ” Glenn says.

More than two years have gone by, and King’s family is desperate for justice. The Texas Rangers, a law enforcement agency that conducts criminal investigations for the Texas Department of Public Safety, investigated King’s death and found no proof of wrongdoing. A spokesman for TDPS confirmed that no criminal act was discovered. The family then asked the local district attorney’s office if it had received a report from the Rangers and was told no. (The Polk County District Attorney’s Office did not respond to a request for comment.) Now, King’s relatives are scrambling to figure out what went wrong.

Almost 1,000 people perish in jail annually, yet prosecutors are doing little if anything to hold the people who run them accountable. According to Dave Shapiro, an attorney with the MacArthur Justice Center at Northwestern’s Pritzker School of Law, criminal wrongdoing behind jail walls is difficult to prove. There is generally no video footage and nobody spreading the message on social media, which is why jail deaths receive far less attention than egregious police arrests and shootings. And even if there’s reason to believe an inmate’s death was caused by a correctional officer, prosecutors are reluctant to charge law enforcement officials with potential crimes committed while they’re on the job.

At any given moment in the United States, approximately 630,000 people are detained in more than 3,000 jails. Seventy percent of detainees haven’t been convicted of a crime, and many are too poor to pay the high bail amounts usually set by prosecutors. Of all pretrial detainees, nearly 70 percent are locked up for drug, property, or public order offenses. Like King, detainees are disproportionately people of color; black people are overrepresented in the jail populations of all 50 states, Hispanics are overrepresented in 31, and American Indians are overrepresented in 17. What’s more, an estimated 64 percent of all jail detainees suffer from mental illness. They are some of the most vulnerable people in the custody of the state, yet there is no reliable way to track how many die of neglect or violence. (The leading causes of death behind bars, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, are illness and suicide, but there are no official statistics on the circumstances that underlie those deaths.)

Take Natasha McKenna, who died in 2015 after being shocked repeatedly with a Taser. McKenna, who had a history of schizophrenia, had been shackled and covered in a face mask at the time of her death. Fairfax County, Virginia Commonwealth’s Attorney Raymond Morrogh ruled that the use of force was justified and no charges were filed. “There is no evidence that any of the deputies acted maliciously, sadistically or with the intent to punish or cause harm to Ms. McKenna at any point in the struggle,” he wrote in a 52-page report that described McKenna as having “superhuman strength.”

Five months later, Michael Sabbie died while begging for medical help at the privatized Bi-State Justice Center in Texarkana, Texas. Instead of receiving treatment, video shows he was body-slammed, pepper-sprayed, dragged, and dumped in a cell, where he died. While the FBI’s Little Rock, Arkansas field office was asked to investigate by the local police, the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division declined to press charges. “After careful consideration, we concluded that the evidence does not establish a prosecutable violation of the federal criminal civil rights statutes,” a representative said last August.

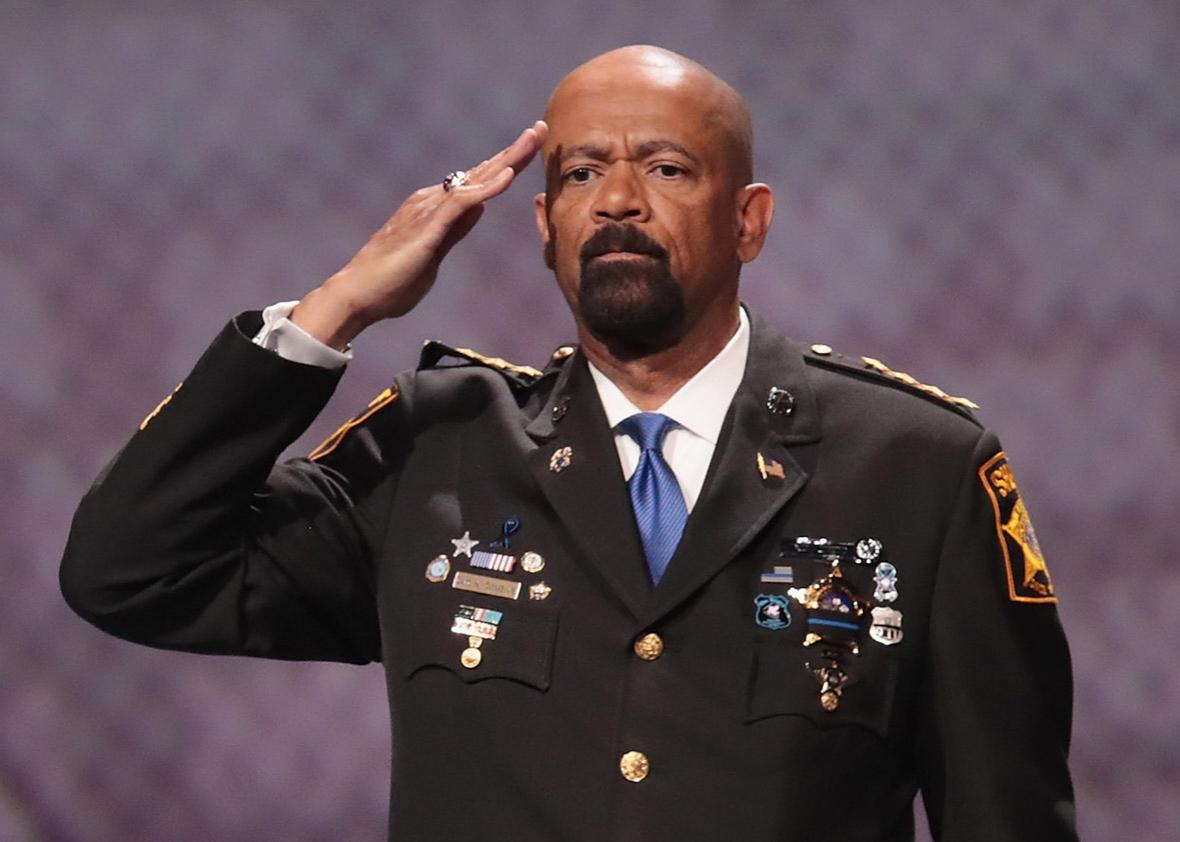

A spate of deaths in Sheriff David Clarke’s Milwaukee County Jail has also made national headlines in the past year. One of those who died was a newborn baby. Another was 29-year-old Michael Madden, who according to a medical examiner died from natural causes. A fellow detainee, though, said a guard accused Madden of faking a seizure and kneed him in the back. The Milwaukee County District Attorney’s Office didn’t file charges in either case.

Another Milwaukee inmate, Terrill Thomas, died of “profound dehydration” eight days after he was thrown into a solitary cell. Inmates are supposed to drink tap water from their sinks, but staff cut off Thomas’ water supply completely. As a result, he languished in isolation, losing 35 pounds in one week before he died. In a rare move, the Milwaukee DA’s office opened an inquest and presented evidence to a jury. Earlier this year, the jury recommended that criminal charges be brought against seven corrections officials. Even so, the DA’s office hasn’t decided whether to file charges.

Even when there are blatant signs of misconduct and excessive use of force, corrections officers are rarely brought to justice. Prosecutors have unchecked discretion to charge whoever they want, and they typically set a higher bar for their colleagues in the world of law enforcement. They are cognizant of the fact that jails are operated by sheriffs and local police whose support they need to keep locking people up. Those groups are represented by powerful unions that fight hard to protect their own. Deceased inmates, on the other hand, generally come from voiceless communities with little financial or political clout.

Prosecutors are also hesitant to go after corrections officers for a more self-serving motive: the fierce desire to win. If they don’t have a slam dunk case, they aren’t likely to run with it. That hasn’t stopped some prosecutors from pursuing justice for the dead. In 2016, a New York City corrections officer was tried and convicted by Assistant U.S. Attorney Brooke Cucinella after fatally kicking an inmate in the head in Rikers Island. Another guard was tried by Assistant U.S. Attorney Hydee Hawkins and convicted for the fatal beating of an inmate in Perry County, Kentucky. In California, the Santa Clara County District Attorney’s Office won a case this month against three jail deputies who beat a bipolar man and left him to die alone in a cell.

For now, though, the most reliable recourse for the relatives of those who die in jail is civil litigation. Natasha McKenna’s family filed a $15.3 million wrongful death lawsuit last June. Michael Sabbie’s family filed a federal complaint in May. Sandra Bland’s family won a $1.9 million settlement from Waller County, Texas.

Nathan King’s relatives, meanwhile, filed a complaint in a Texas district court. But without lawyers, it’s nearly impossible for them to launch an investigation of their own. For now, there’s nothing they can do but wait and see what the court decides to do with their complaint. “[The] anger doesn’t feel like it’s gonna leave, because no one is out there saying ‘I’m going to help you get over this,’ ” Glenn says. “You feel the world is telling you—and the system that the world has created is telling you—this person never counted anyway.”