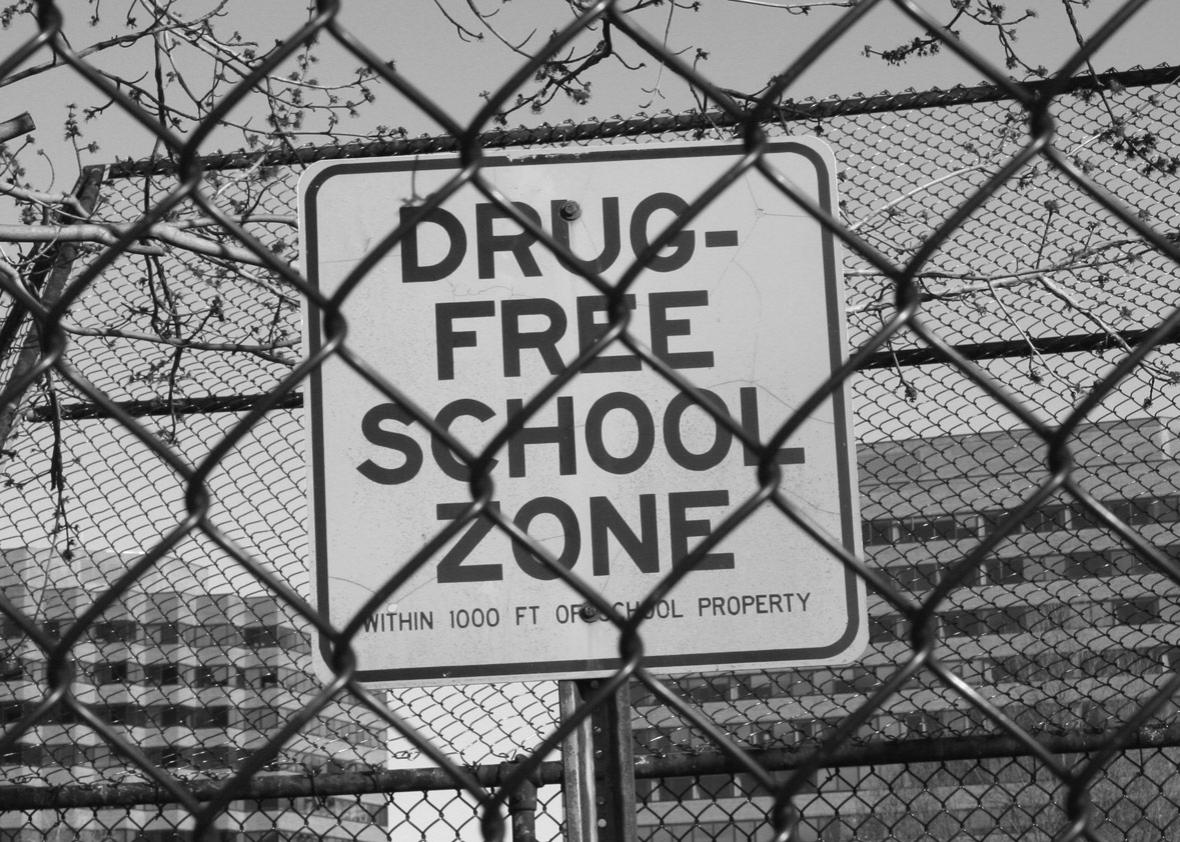

Mandatory minimum sentences are among the most lasting and damaging result of previous eras of draconian drug policy. They include, for example, laws requiring at least two years in prison for all drug crimes within 1,000 feet of a school. Enforcement can lead to irrational outcomes, locking people up for very minor crimes and stripping away discretion from judges.

Moreover, research has shown that tough-on-crime policies like mandatory minimums have not been effective at reducing crime. Instead, mandatory minimum laws have been shown to cause expanded racial disparities in sentencing. States that shifted away from minimums have seen lower prison populations and bigger cost savings. And all 17 states that decreased their prison populations over the last decade saw a reduction in crime rates.

Many states are leading the charge in doing away with mandatory minimum laws. From Massachusetts to Iowa to Florida, momentum has grown in state legislatures this year to rewrite laws that guarantee long sentences for low-level offenders. The reform has, in most places, won broad bipartisan support, from elected officials, judges, advocacy groups on the right and the left, and law enforcement officials.

One of the only major groups to consistently oppose reforming mandatory minimums is district attorneys. In almost every state considering reform, local DAs and DA associations have lined up against it, arguing that reducing mandatory sentences would lead to an upswing in drug abuse. No matter that this fearmongering is likely untrue. The national scare over opioid use and overdose is fueling the district attorneys’ campaign for tougher drug laws.

The district attorneys claim they need the threat of a long, mandatory sentence as leverage to cajole defendants into pleading guilty to lower crimes and that mandatory minimums ensure a measure of consistency in sentencing.

Boil away this rhetoric and you get to the heart of the argument: “It’s all about power,” said Kevin Ring, the president of the advocacy group Families Against Mandatory Minimums. “Mandatory minimums have given DAs—who already had unreviewable charging authority—the ability to pick sentences and cut judges out of the picture.”

While the district attorneys’ position may be understandable from their perspective, the tide is turning against them. Take Massachusetts. For the past decade, state Sen. Cynthia Creem has introduced legislation that would eliminate mandatory minimums for nonviolent drug offenders, inspired by stories of women in the state serving years for nonviolent drug crimes. For the most part, her bills went nowhere, with the legislature making only minor changes that slightly increased the drug amounts necessary to trigger minimum sentences.

This year is different, Creem argues. “We have a really good nucleus of people in various walks of life that are making criminal justice reform a priority, and we did not have that before,” she says. Notably, the chief justice of the state Supreme Court, Ralph Gants, has vocally endorsed the idea of ending minimums, saying it “makes fiscal sense, justice sense, policy sense and common sense.” The state sentencing commission endorsed a proposal to end mandatory minimums for all crimes except murder. Legislative leaders have told Creem her bill is a priority for them. Gov. Charlie Baker, a Republican, has also said in the past that he supports mandatory minimum reform in the abstract. Even a group of sheriffs from the state have backed the bill.

The state’s DAs are some of the only elected officials opposing reform. DA Dan Conley of Suffolk County, which includes Boston, has excoriated the proposal, arguing that nonviolent drug offenders “simply don’t exist” in Massachusetts prisons—an idea contradicted by state corrections data. (Conley’s office did not respond to a request for comment.) Their insistence may be impeding progress: Without opposition from DAs like Conley, mandatory minimum reform would have taken place much more rapidly, Creem thinks. “What they say does influence the legislators,” she said.

Progress isn’t just being made in blue states. In deep-red Iowa, the state legislature has approved a reform bill that would eliminate mandatory minimum sentences for some drug felonies, make more people convicted of drug crimes eligible for parole, reduce the disparity between crack and powder cocaine sentences, and give judges discretion to abandon mandatory sentences in some cases when they determine the required sentences would lead to “substantial injustice.” The bill unanimously passed the state Senate and House of Representatives and is waiting for the signature of Gov. Terry Branstad, who has supported criminal justice reform in the past.

Another bill in Nebraska, which was narrowly approved by the state Senate on March 8, would eliminate three- to five-year mandatory minimum sentences for people convicted of possessing or intending to distribute cocaine, heroin, or methamphetamine. It was intended as a compromise bill, although conservatives and Gov. Pete Ricketts still oppose it, meaning it will likely be vetoed rather than become law. It’s been vigorously fought by district attorneys and the state’s attorney general.

In Florida, there’s a coalition of conservative groups urging state lawmakers to support several bills that would reduce mandatory minimum sentences for drug crimes. The state’s minimums are some of the strictest in the country, Ring said, but no reform bill has seen legislative action so far this year. The state House, meanwhile, has approved a bill creating new mandatory minimum sentences for dealing or using opioids, focusing on the drug fentanyl—a sign of how the national opioid crisis has led to more unhelpful tough-on-crime rhetoric.

Pennsylvania is on the other side of the issue: In 2015, the state Supreme Court declared mandatory minimum sentencing laws unconstitutional. But now a Republican state representative who’s a former prosecutor is working to bring them back, with the urging of state district attorneys. Rep. Todd Stephens introduced a bill that would restore two-year minimum sentences for small drug crimes and drug offenses that occur within school zones, and five years for repeat violent crimes involving real or fake guns.

Stephens, who worked as a prosecutor for 10 years in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, argues that his bill would lead to lower mandatory minimums than Pennsylvania had before the state Supreme Court ruling. “Our law enforcement community believes that mandatory minimums are a necessary tool to help protect the public,” he says. “As a prosecutor myself, I know having them makes the streets safer.”

But opponents say there’s no evidence that the bill would actually increase safety. Even the state department of corrections has urged lawmakers to oppose the bill, saying it would increase prison populations when facilities are already over capacity and cost the state millions of dollars. The bill has moved forward in the House.

Reform advocates say the progress they’ve made so far is precarious. With worry growing around the country about addiction and opiates, district attorneys and pro–mandatory minimum legislators could take advantage of the panic and reintroduce these minimums. Conley, the Boston DA, has started to use this argument: “In the midst of an opioid crisis, are we going to be more lenient on heroin traffickers?” he said in a February interview criticizing minimum reform.

It’s a frightening regression—lawmakers, rather than investigate other ways to assist addicts, seem committed to going back to outdated policies that don’t work. “Some lawmakers seem to be throwing up their hands and saying we’d better pass tough new drug laws,” Ring says. “Even though there’s no evidence that public safety is enhanced in jurisdictions that have mandatory minimums.”