On May 12, Lucie Charlebois, Québec’s minister of public health, proudly announced that two centers where people would be able to inject illicit drugs under a nurse’s supervision would soon open in Montreal. “I’m containing my emotions,” Charlebois exclaimed.

Earlier that same day, U.S. Attorney Jeff Sessions had directed prosecutors to seek the harshest possible charges in federal drug cases, presenting the conventional drug war wisdom as though its veracity required little explanation. “We know that drugs and crime go hand in hand,” said Sessions, accepting an award from a New York City police union. “They just do. The facts prove that so.”

Sessions’ facts are actually in short supply. The attorney general justified his new charging policy by pointing to rising murder rates and to an overdose crisis fueled by increasing opioid use. In reality, violent crime remains at close to the lowest levels they’ve been in a half-century, and there is no evidence that local, year-to-year fluctuations in particular cities represent a durable nationwide reversal. What’s more, experts have concluded that decades of mass incarceration played little if any role in lowering crime rates. At the same time, the lifesaving benefits from supervised injection sites are grounded in evidence, and experts say that they are urgently needed to confront the opioid overdose crisis.

Still, Sessions has pledged to “reverse [the] trend” of high potency, low-price opioids even though decades of imposing draconian sentences on drug dealers have done nothing of the sort. Instead, the drug war has incentivized dealers to adulterate the heroin supply with fentanyl, a dangerously potent synthetic opioid that is killing people in growing numbers. Because it is easier to smuggle smaller quantities of a stronger drug than larger quantities of a weaker one, under prohibition, the more potent a drug, the greater the profits and the lower the risk of detection. The result is that incredibly potent fentanyl, cheap to procure and easy to smuggle, is everywhere, and overdose deaths are skyrocketing.

Canada, for one, is trying something different.

The U.S. and our neighbors to the north have overlapping drug markets, and both countries face an extraordinary public health crisis from fentanyl and also from sometimes dangerous, new psychoactive substances adulterating the supply of cocaine, methamphetamine, and MDMA. The responses playing out in the two capitals, however, are based on two profoundly divergent models.

In 2015, Liberal Party Leader Justin Trudeau defeated Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper in a campaign where drug politics were front and center. During his nearly 10 years in office, Harper staunchly opposed harm reduction measures, including failed legal battles to shutdown Insite, Vancouver’s supervised injection center, and Providence Crosstown Clinic, which provides prescription heroin. Now, Trudeau’s government is shifting away from criminalization, moving to open supervised injection sites nationwide, to expand access to prescription heroin, and to legalize recreational marijuana.

The contrast with President Trump—who ran a law-and-order campaign and picked an attorney general who has claimed that “good people don’t smoke marijuana”—is stark.

In Montreal, the announcement of the injection sites coincided with the convergence of what organizers reported was more than 1,000 drug policy advocates and researchers from 70 different countries for the Harm Reduction International Conference.

Harm reduction is a public health approach to drug use premised on the idea that the aim of policy should be to maximize health and minimize damage. The harm reduction movement is made up of academics, health professionals, and activists—including active drug users—who for decades have used science and research to guide their activism and policy proposals, such as the introduction of clean needle exchanges and the rollout of naloxone, a drug that reverses opioid overdoses.

Monique Tula, executive director of the U.S.-based Harm Reduction Coalition, told attendees that the Trump administration’s approach represented “a wholesale rejection of science.”

“It’s completely regressive,” Tula said in an interview. “Utterly draconian policies, [there was] utter hysteria around the crack epidemic and the result then was to lock everyone up. The idea is if we put a dent in the supply then demand will go down accordingly. It’s not what happens.”

As with economics, supply-side drug policy is a god that fails time and again. By contrast, research has made it clear that supervised injection sites—where people can shoot up illicit opioids and other drugs while monitored by a nurse—save lives by preventing fatal overdoses and the spread of HIV and hepatitis C.

Those who wage the drug war, like global warming deniers, are continuing to cast evidence aside. The reason they do so is simple: The science doesn’t help their cause.

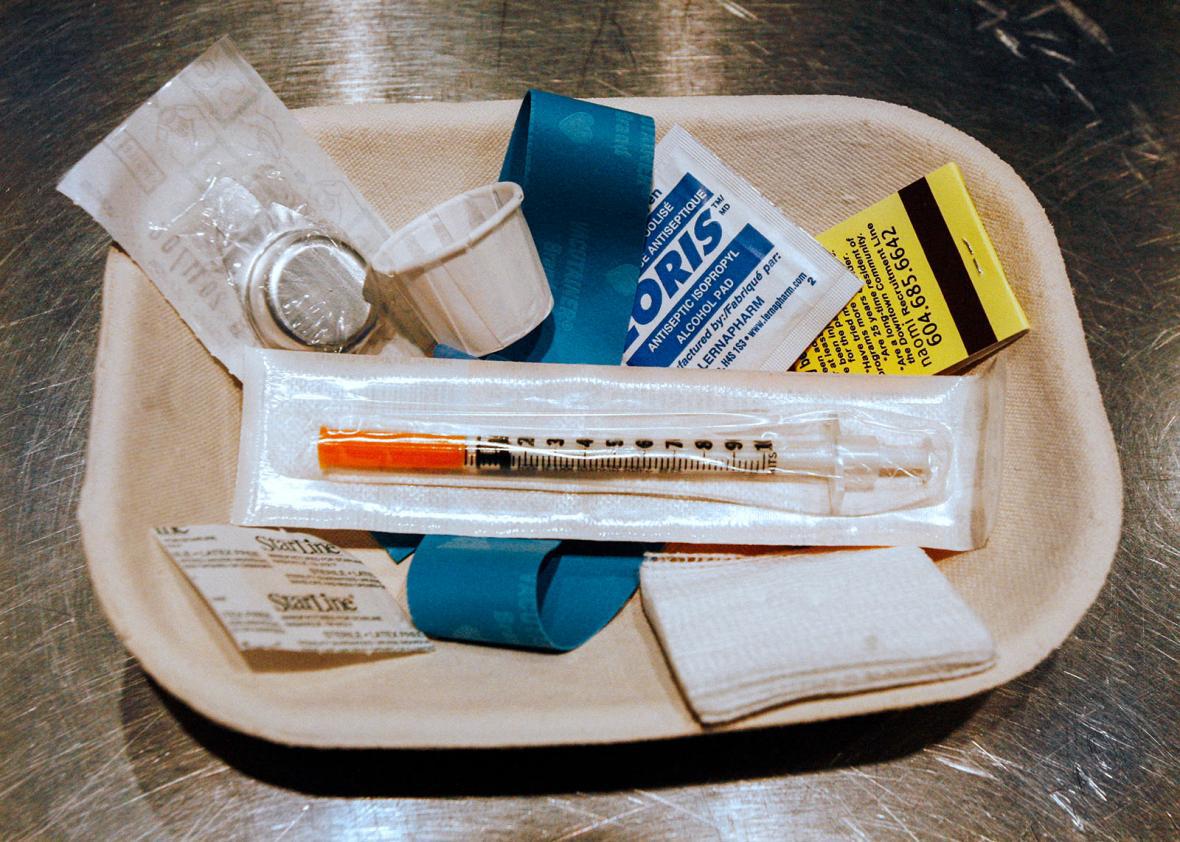

In Montreal, Charlebois took reporters on a tour of a downtown site that will soon open its doors to injection drug users. It is bright, antiseptic, and will be available to those who need it 22 hours a day. On their first visit, drug users will register in the waiting room and inform staff as to what drugs they plan on using, so that the facility can respond accordingly to a complication or overdose. The user then walks into the injection room and takes a seat at a booth with the relative privacy of a partitioned urinal, watched by staff sitting at a desk, like a nurses station, in the center of the room. If it’s busy, there’s a take-a-number sign like at a supermarket deli counter or the DMV.

It’s a remarkably banal location for people to safely use illegal drugs. Its very existence is a striking repudiation of the drug war.

Studies presented at the conference found evidence that crack users may successfully use marijuana to moderate their crack habit, that psychedelic drug use may decrease suicidality among sex workers, and that drugs sold in online cryptomarkets—markets like the website Silk Road, closed by U.S. law enforcement—appear less likely to be contaminated than those sold in traditional drug markets.

Another found that prescribing the opioid hydromorphone was a good substitute for prescription heroin. Heroin-assisted treatment, in which users can access diacetylmorphine, heroin’s active ingredient, has been shown to be an effective way to minimize the harms of heroin use—but in the U.S., it has been blocked by prohibitionist policies. Alarmingly, the U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price this month went so far as to criticize well-established opioid substitution treatments that provide users with methadone or buprenorphine.

“If we’re just substituting one opioid for another, we’re not moving the dial much,” said Price. “Folks need to be cured so they can be productive members of society and realize their dreams.”

The dream of a cure, or of a drug-free America, however, is killing people.

“There’s real movement on the local level in the U.S., and some very thoughtful progressive stuff happening,” said Ethan Nadelmann, the founder and until recently director of the U.S.-based Drug Policy Alliance. “But obviously, Trump, and Sessions, and now Price—they’re maniacs basically.”

One of the most critical pieces of research presented at the conference was a study out of Vancouver, which tested the content of drugs being used at Insite. The results were disturbing: Fentanyl was identified in 83 percent of the heroin checked and, alarmingly, in much of the cocaine and methamphetamine as well.

But no one has ever died of an overdose at Insite. Rather, Insite saves lives: It has treated more than 6,900 overdoses since opening in 2003, more than 3,110 of which required naloxone, said Dr. Mark Lysyshyn, a medical health officer at Vancouver Coastal Health.

Indeed, drug overdose deaths in the United States have surpassed deaths from AIDS at the peak of that crisis in the mid-1990s. In 2015 drug overdose deaths rose 11 percent, reaching almost 53,000. Heroin overdoses alone surpassed gun homicides. With AIDS, it took militant action from groups like ACT UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, to force the government to treat the disease as a public health crisis that required new medications and harm reduction measures like condoms and needle exchanges. It’s not just law-and-order but the emphasis on treatment and recovery that is preventing the harm reduction movement from gaining a similar foothold today: Getting clean is important for those people who choose or need to do so, but the premise that all solutions begin with recovery crowds out debate on how to keep continuing users healthy.

Even Canada’s bold reforms won’t be enough to confront an opioid crisis of staggering proportions. In March alone, an estimated 120 people died from illicit drug overdose deaths in British Columbia. At the conference, drug user activists protested Minister of Health Jane Philpott’s speech with signs reading “They Talk We Die,” demanding a faster and more dramatic response.

“Essentially [we need] to legalize drugs and regulate the market. We have problems like this in the food sector all of the time,” said Lysyshyn. “We get a product that’s contaminated, it’s recalled, within days, the problem is over. And that’s the type of solution that we need here too.”

Decriminalization for personal use would be a major first step. In Portugal, which decriminalized personal use in 2001, drug-related deaths and injection drug use–related HIV infections have plummeted. But decriminalization alone fails to deal with regulating the supply of drugs and reducing the terrible bloodshed that accompanies unregulated illicit markets in places where drugs are manufactured or trafficked, such as Colombia, Central America, and Mexico.

In Canada, it has been localities that have led the way in harm reduction. Vancouver opened the first legal needle exchange in North America and the first injection facility, even as the Harper government fought harm reduction measures from taking hold on the national level.

The United States, of course, is far less equipped to fight fentanyl. With Trump in office, advocates are pushing for localities to take the lead. Currently, supervised injection sites are under consideration around the country, including in Massachusetts and in metro Seattle. Prescription heroin, which will likely be one of the harm reduction movement’s top priorities if supervised injection sites begin to open, is slowly entering the discussion.

It’s a conversation, however, that the Trump administration seems determined to shut down, retreating to the comforting, zombielike illusion that government can use tough talk and mass imprisonment to will illicit drug use out of existence. Announcing the push for harsher sentencing, Sessions said that “together we will win this fight.”

But Americans are dying in extraordinary numbers. What we’re witnessing is not just an opioid crisis but a public health emergency in part created and disastrously exacerbated by the war on drugs. This is a fight that targets drug users for stigmatization and incarceration—particularly and not coincidentally the minority subset of drug users who are poor or racially marginalized. It also facilitates the toxic adulteration of their drug supply. Prohibition ensures that drugs will be unregulated and potentially far more dangerous than they would be if the same regulatory approach that is applied to licit drugs—or, for that matter, food and cosmetics—were applied to illicit ones. In free-market America, regulations often fall short, but they are far better than no regulation at all.

But measures to regulate drug quality are not under serious consideration anywhere in North America for a simple reason: It would require legalization, and that would be the end of the drug war.