On Tuesday night, Rolando Ruiz was executed in Texas after spending more than two decades on death row. The legal team representing Ruiz, who killed Theresa Rodriguez as part of a murder-for-hire scheme in 1992, filed multiple petitions with the Supreme Court for a stay of execution, one of which argued that his fate constituted cruel and unusual punishment. All of those petitions were denied.

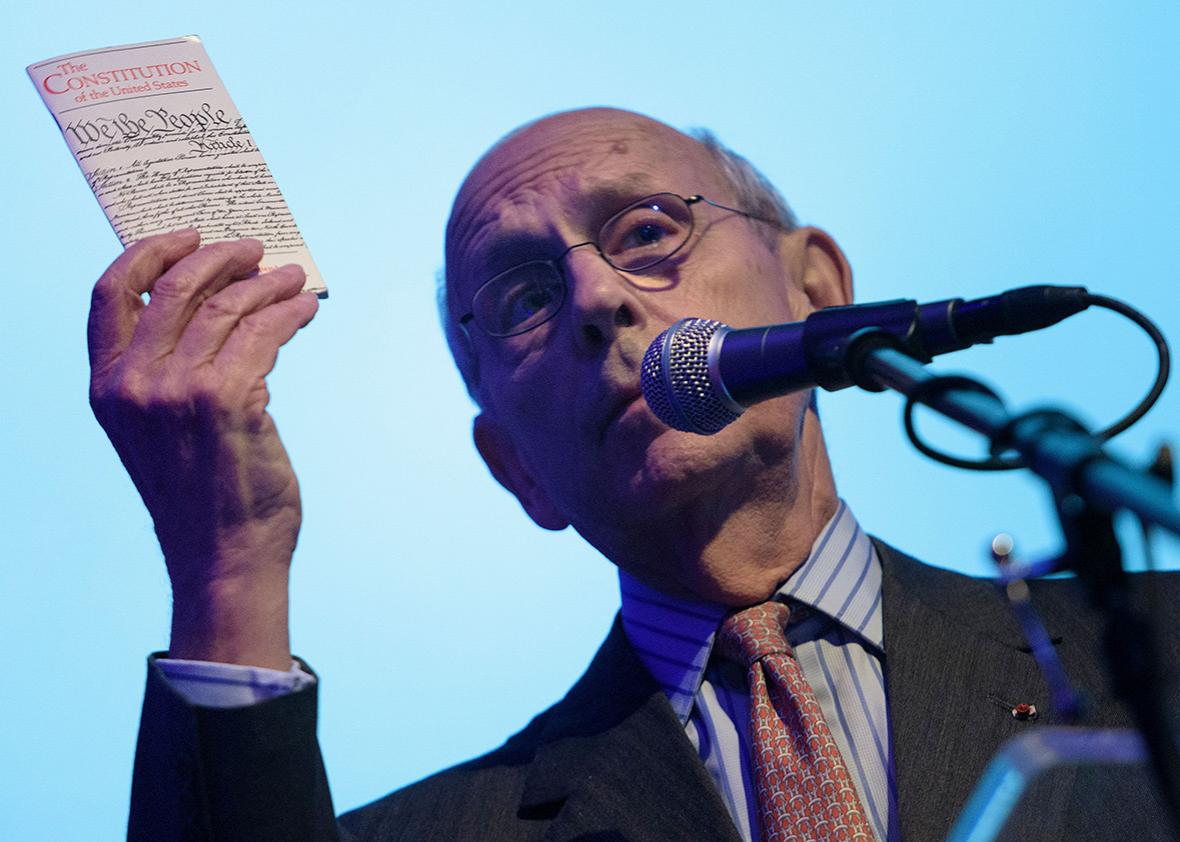

Justice Stephen Breyer, who dissented from his colleagues’ denial of certiorari, believed Ruiz’s Eighth Amendment claim was “a strong one” and worth a closer look. “This Court long ago, speaking of a period of only four weeks of imprisonment prior to execution, said that a prisoner’s uncertainty before execution is ‘one of the most horrible feelings to which he can be subjected,’ ” wrote Breyer. Ruiz, Breyer notes, endured that uncertainty for 22 years.

Ruiz was one of the nearly 40 percent of death row prisoners in the U.S. who have spent 20 or more years awaiting execution. Breyer pointed out that like most inmates sentenced to death, Ruiz lived in solitary confinement, where he suffered hallucinations, suicidal thoughts, and depression. These psychological symptoms are common among prisoners placed in solitary confinement, and they run rampant among Texas inmates. As I described in a piece published earlier this week, death row inmates in Texas “spend 23 hours per day isolated in 60-square-foot cells. They exit only to shower or exercise and are handcuffed, stripped naked, and subjected to a full body search when they do leave their cells.” Combining that isolation with a looming and uncertain execution date, Breyer argued in his dissent, does profound psychological harm.

In part because of the poor representation so frequently provided to capital defendants, a lengthy appeals process is unquestionably necessary. Without it, a defendant’s potentially valid legal claims may never be heard in a court of law.

Ruiz’s case is a telling example. A federal district court judge in 2005 recognized that “the quality of representation petitioner received during his state habeas corpus proceeding was appallingly inept. … [Ruiz’s] counsel made no apparent effort to investigate and present a host of potentially meritorious and readily available claims for state habeas relief.” These potentially viable claims included allegations that his trial lawyer should have presented mitigating evidence that might have convinced a jury to sentence him to life. Ultimately, that court ruled that the claims were procedurally barred—another complicated and devastating aspect of our nation’s death penalty laws.

This is not the first time Breyer has challenged the constitutionality of long delays before execution or the use of solitary confinement. In a dissent in the 2015 case Glossip v. Gross, he stressed that “excessive delays from sentencing to execution can themselves ‘constitute cruel and unusual punishment prohibited by the Eighth Amendment.’ ” And prolonged isolation, Breyer wrote, “produces numerous deleterious harms.”

Justice Anthony Kennedy has also expressed grave concern about the confinement of death row prisoners. In a 2015 case about jury selection, Kennedy dedicated four pages of his concurring opinion to questioning solitary confinement. The defendant, Hector Ayala, had spent more than 25 years in isolation. “Research still confirms what this Court suggested over a century ago: Years on end of near-total isolation exact a terrible price,” wrote Kennedy.

Pointing to Kennedy’s opinion in Ayala, Breyer wrote this week that Ruiz’s case is an opportunity to consider solitary confinement with “constitutional scrutiny.” In the last paragraph of his three-page dissent, Breyer noted, “If extended solitary confinement alone raises serious constitutional questions, then 20 years of solitary confinement, all the while under threat of execution, must raise similar questions, and to a rare degree, and with particular intensity.”