In 1979, Arthur Lee Giles, then 19 years old, was sentenced to death in Blount County, Alabama. Nearly 40 years later, he is still waiting to be executed. His glacial march to execution exposes a conundrum at the heart of America’s death penalty. Condemned prisoners often spend decades on death row before being executed—if the execution ever happens at all—a fact that undermines any retributive value capital punishment might provide.

Approximately 40 percent of the 2,739 people currently on death row have spent at least 20 years awaiting execution, and 1 in 3 of these prisoners are older than 50. (This is according to data collected by the Fair Punishment Project and sourced from the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund, the Federal Bureau of Prisons, and state corrections departments.)

According to a Los Angeles Times investigation, roughly two dozen men on California’s death row require walkers and wheelchairs, and one is living out his days in bed wearing diapers. In North Carolina, nine death row prisoners have died of natural causes since 2006—the same year the state last executed someone. These delays suggest that executions must be sped up significantly.

And yet, the process that creates those delays cannot be eliminated without a corresponding increase in the risk of wrongful executions. Since 1973, 157 men and women have been exonerated from death row. The average time from conviction to exoneration is nearly a decade. Glenn Ford spent nearly 30 years on Louisiana’s death row in solitary confinement. Convicted of first-degree murder in 1984, new evidence later revealed Ford’s innocence. He was exonerated in 2014, just 16 months before he died of lung cancer. That same year, after three decades on North Carolina’s death row, Henry Lee McCollum was cleared by DNA of the rape and murder of an 11-year-old girl and released from prison.

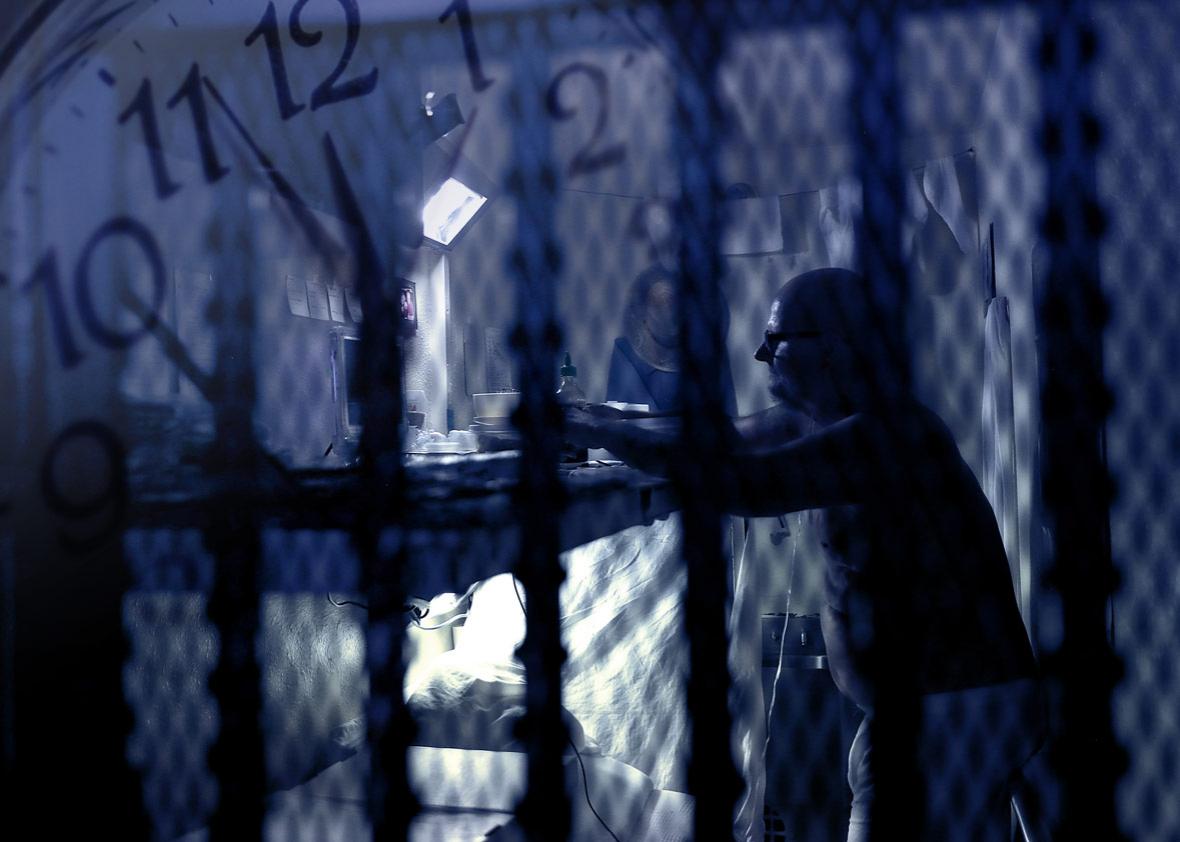

Behind this conundrum rests a profound moral and legal problem. Decades spent awaiting an uncertain execution inflicts an additional and nakedly cruel layer of punishment on the condemned. Most death row inmates are housed alone for years in tiny concrete cells even as a growing body of evidence suggests the psychological burden of solitary confinement is tantamount to torture. In Texas, for example, death row prisoners await their fates in the Allan B. Polunsky Unit, a Polk County prison where they spend 23 hours per day isolated in 60-square-foot cells. They exit only to shower or exercise and are handcuffed, stripped naked, and subjected to a full body search when they do leave their cells.

In 2015, Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy questioned the humanity of confining prisoners “in a windowless cell no larger than a typical parking spot.” In his concurring opinion in Davis v. Ayala, Kennedy cited an 1890 Supreme Court ruling that solitary confinement represented “a further terror and peculiar mark of infamy” for prisoners who’ve been sentenced to death. That kind of isolation can “exact a terrible price” and “literally drives men mad,” Kennedy wrote.

With public support for executions at historic lows, death row delays seem likely to increase. Just 20 of the nearly 3,000 prisoners on death row nationwide were executed last year.

California is a prime example. In 2014, a federal judge wrote that the state’s capital punishment system is actually a sentence of “life without parole with the remote possibility of death.” The judge calculated that “just to carry out the sentences of the 748 inmates currently on Death Row, the State would have to conduct more than one execution a week for the next 14 years.” That’s an unfathomable outcome in any state, much less in one that has not performed a single execution in more than a decade.

This concern that the delays themselves amount to an unintended yet highly troubling consequence was flagged in 1995 by then–U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, when he acknowledged in a dissent in the case Lackey v. Texas that executing a prisoner who had already spent more than 17 years on death row might violate the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

In an effort to combat these delays, California voters narrowly passed Proposition 66 in 2016, which promised to speed up executions by imposing more severe limitations on the death penalty appeals process. Yet Prop 66 has already faced significant constitutional challenges, and the California Supreme Court has stayed the initiative pending the outcome of a case filed by former state Attorney General John Van de Kamp and Ron Briggs. Forty years ago, Briggs worked with his father—who helped author the successful statewide proposition reinstating the death penalty in California—to push for that proposition’s passage.*

If the Constitution does not permit California’s attempt to speed up executions at the expense of risking fairness and accuracy, the decades-long delays will almost certainly persist—resulting perhaps in legal grounds for relief for condemned inmates.

In a dissent written last year, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer challenged the court’s decision not to review the case of Henry Sireci, who has spent more than 40 years on Florida’s death row. Noting that the Berlin Wall was still standing at the time when Sireci received a death sentence, Breyer wrote, “Forty years is more time than an average person could expect to live his entire life when America constitutionally forbade the ‘inflict[ion]’ of ‘cruel and unusual punishments.’ ”

Breyer, however, could not garner enough votes from his colleagues to decide the issue of whether these delays constitute cruel punishment. And thus the dilemma persists. When it comes to the death penalty, it appears we cannot enact the constitutional protections necessary to prevent wrongful executions without causing prisoners the additional harm of decades-long waits for their punishments to be implemented.

*Correction, March 9, 2017: This piece misstated that John Van de Kamp and Ron Briggs wrote the proposition reinstating the death penalty in California. Briggs’ father helped write the proposition while John Van de Kamp was not involved in its authorship. (Return.)