As a young child, Jason McGehee carried his dog Dusty around with him everywhere he went. He dressed him in pet clothes, put his birthday on a paper calendar, and went to bed each night with the dog sleeping beside him. McGehee’s aunt filed a legal declaration stating that his mother suffered from chronic depression and abused McGehee. His aunt also alleged that McGehee’s stepfather was sadistic. At a family dinner, she claimed, he kicked Dusty to death using his pointy boots as weapons and forcing McGehee to watch. When the dog died, “[t]hat was the turning point,” McGehee’s aunt later observed. “Jason was never the same after that.”

McGehee also suffers from bipolar disorder, which runs in his family. According to an expert evaluation, he may have some impairment in his frontal lobe, the area of the brain responsible for judgement, problem solving, and emotional regulation. Symptoms of mental illness emerged during childhood, but his mother allegedly did not get him help, believing he was “possessed by the devil.”

At 21 years old, Jason lived with several friends in a house without utilities, supporting himself by passing stolen checks and committing other petty crimes. After a frequent houseguest named John Melbourne told the police about the stolen checks, the housemates and Melbourne had a physical altercation that culminated in Melbourne’s death. McGehee received the death penalty. His 17-year-old co-defendant, who admitted to strangling Melbourne with an electric cord until he died, got a sentence of life without parole.

Jason McGehee is one of the eight men Arkansas intends to execute between April 17 and April 27. (McGehee’s execution is scheduled for the 27th.) Arkansas will execute more people in that 11-day period than every state except Georgia did all of last year. A new report released by the Fair Punishment Project reveals that at least six of the eight men likely suffer from crippling mental impairments. But juries never heard much evidence of such impairments because of the shoddy representation the men received at trial. In two cases where there was little evidence of serious mental impairment, it appears as though no lawyer bothered to conduct a thorough investigation into the client’s background.

Under the Eighth Amendment, the death penalty must be reserved for the worst of the worst—those who commit the most heinous homicides and whose personal culpability makes them especially worthy of blame. The Supreme Court has recognized that intellectual disabilities “[lessen] moral culpability and hence the retributive value of the punishment.” Executing those who fall into that category serves “[n]o legitimate penological purpose,” the court has found, and “violates his or her inherent dignity as a human being.”

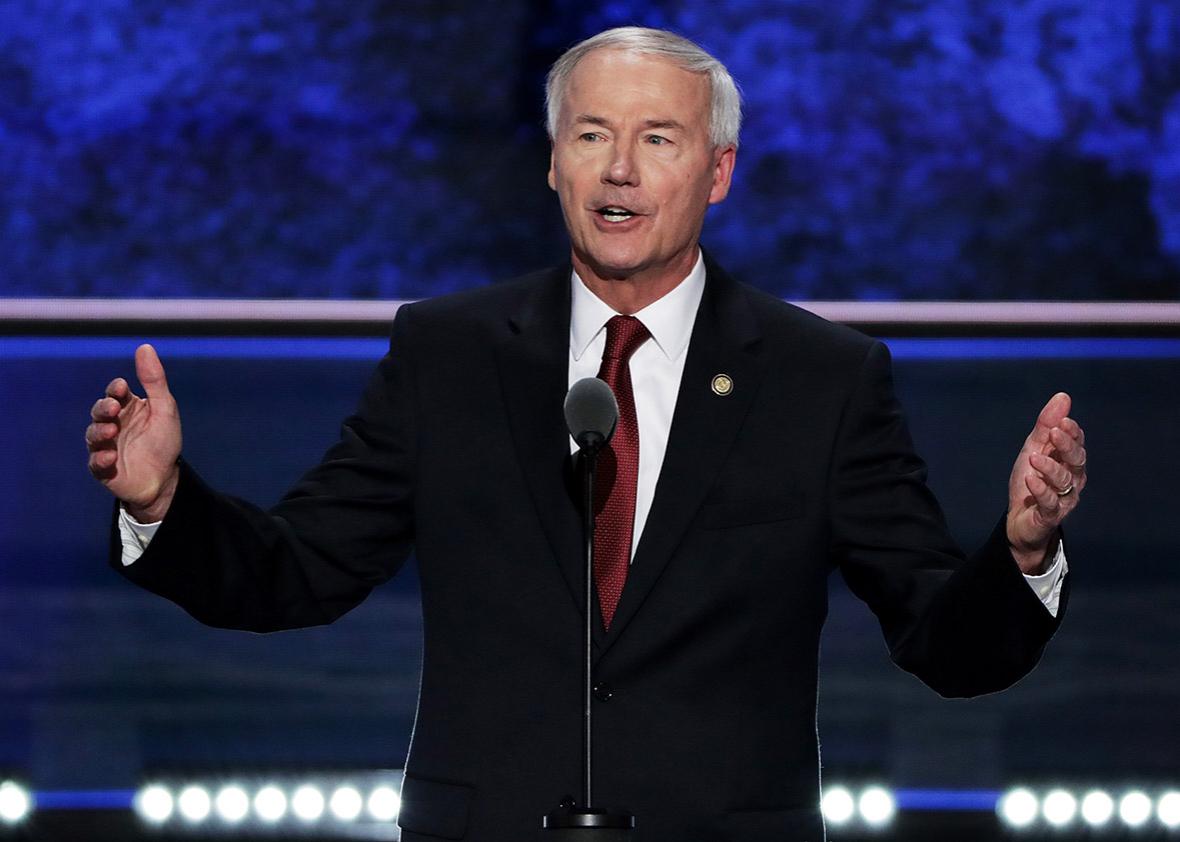

But unless Arkansas’ governor intervenes or a court stays these executions, the state will kill eight men who either have debilitating impairments that diminish their moral culpability or else have lawyers who likely never performed the type of investigation that might reveal such impairments.

Like Jason McGehee, Jack Jones has bipolar disorder and has twice tried to commit suicide, most recently by jumping off a bridge. As a child, Jones thought the only way to be safe from his hallucinations was to hold very still. In a legal declaration, an expert witness who reviewed Jack’s medical records described how Jones’ father physically abused him, and also how he was kidnapped and brutally raped by strangers. Jones is scheduled for execution on April 24. Marcel Wayne Williams experienced horrific sexual abuse as well. In a post-conviction court hearing, a forensic psychologist described how Williams’ mother started pimping him out for sex when he was 10 and reported that Williams was gang-raped by three men as a teenager while serving time in an adult prison. The expert, Dr. David Lisak, also testified that Williams’ mother once poured boiling water on him and (in a different incident) covering him in tar. Williams, too, will be killed by the state on April 24.

While the Supreme Court has ruled the death penalty should be reserved for the most culpable offenders, it has developed categorical bars against executions of the insane, the intellectually disabled, and those under 18. There are three additional men scheduled for execution in April who arguably fall within these categories. The court has held that a state cannot execute a person unless he not only knows that he is going to be executed, but also rationally understands why. Yet it appears as though Bruce Ward does not even realize he will be killed. A diagnosed paranoid schizophrenic, Bruce thinks he is in jail because of “demonic forces” and because God is preparing him “for a special mission as an evangelist.” According to Ward’s lawyers, he thinks there are “resurrected dogs” in the prison, and he has asked his attorneys to hold onto his execution warrant so he can hang it by his office desk when he leaves prison. Ward’s execution is scheduled for April 17.

In Atkins v. Virginia, the Supreme Court ruled that states lack the “power to take the life” of anyone with an intellectual disability. In Hall v. Florida, and again just this week in Moore v. Texas, the court reaffirmed that ruling and made clear that states’ definitions of intellectual disability must be informed by medical standards, overturning sentences where states eschewed “the medical community’s diagnostic framework” for evaluating intellectual disability. Two of the Arkansas cases may fall within this medical definition. Kenneth Williams has an IQ of 70, which puts him squarely within the intellectual disability range. Don Davis, whose IQ measured at 69 and 77 in two separate tests, is at the very least borderline intellectually disabled. Davis will be executed on April 17, Kenneth Williams on April 27.

This kind of evidence often convinces jurors to spare a defendant’s life. According to findings from the Capital Jury Project—a group of researchers who study jurors’ decision-making in death penalty cases—evidence of reduced culpability in the form of intellectual disability, mental illness, or childhood trauma is extremely compelling to jurors deciding whether to spare someone’s life. But in almost none of these Arkansas cases did a jury ever hear about the defendant’s crippling mental illness, neurological impairments, intellectual disabilities, or allegations of abuse.

Ledell Lee’s case is a tragic example. His trial lawyers repeatedly asked to be removed from the case and even appealed to the Arkansas Supreme Court citing a “gross [ethical] conflict”—the source of the conflict is unclear—that could impede the representation of their client, but the judge refused their request to withdraw. Perhaps unsurprisingly, they did not investigate Lee’s life history. Lee’s first post-conviction attorney admitted to being drunk during a post-conviction hearing and repeatedly stated “blah blah blah” while in court.

Lee eventually received new lawyers, but the Arkansas Supreme Court rejected their briefs twice for failure to comply with court standards. Later, another attorney withdrew from the case after representing Lee for 10 years. After all that time, she claimed not to have a file on Lee’s case. And yet another lawyer had to surrender his law license to “prevent possible harm to clients” because he himself suffered from a serious mental illness. Lee’s execution is scheduled for April 20.

In the case of Stacey Johnson, too, there is no evidence that any lawyer ever conducted a meaningful mitigation investigation into his life history. With only three weeks until Johnson’s April 20 execution date, it appears as though no one ever will.

In the 1990s, when all of these men were first sentenced to death, the nation had a very different relationship with the death penalty than it does today. In 1992, then–Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton left the presidential campaign trail to oversee the execution of Ricky Ray Rector, a man with an IQ of 70 who gave himself a partial lobotomy. When the guards took him to the execution chamber, Rector left his dessert—a pecan pie—to eat later. That year, more than three-quarters of people in the United States supported the death penalty, and in three separate years in the 1990s more than 300 Americans were sentenced to death.

These eight men are holdovers from a bygone era. Today, public support for the death penalty has fallen to its lowest level in more than 40 years, and only 30 death sentences were handed out in the whole country last year. Among the reasons the death penalty has lost its luster are concerns over executing people with intellectual impairments or serious mental illnesses. Now, Arkansas is poised to execute a string of people with crippling impairments at a clip that would embarrass any Southern governor at the height of the 1990s execution frenzy.

Gov. Asa Hutchinson should step in and halt these executions, but if he does not, the buck stops with the U.S. Supreme Court. If, as Justice Anthony Kennedy recently wrote on behalf of the court in Hall v. Florida, executing a person with an intellectual disability violates the inherent dignity of that person, then what does it say about Arkansas—and frankly, the court itself—if the executions of these broken, vulnerable men are allowed to proceed?