If you like what you see, please encourage a friend, family member, or enemy to sign up for the Today in Slate email newsletter here.

Slate–y heads,

Here’s an incomplete list of who has problems on Wednesday: white people, judges and criminals, liberals, and spooners. Good luck out there.

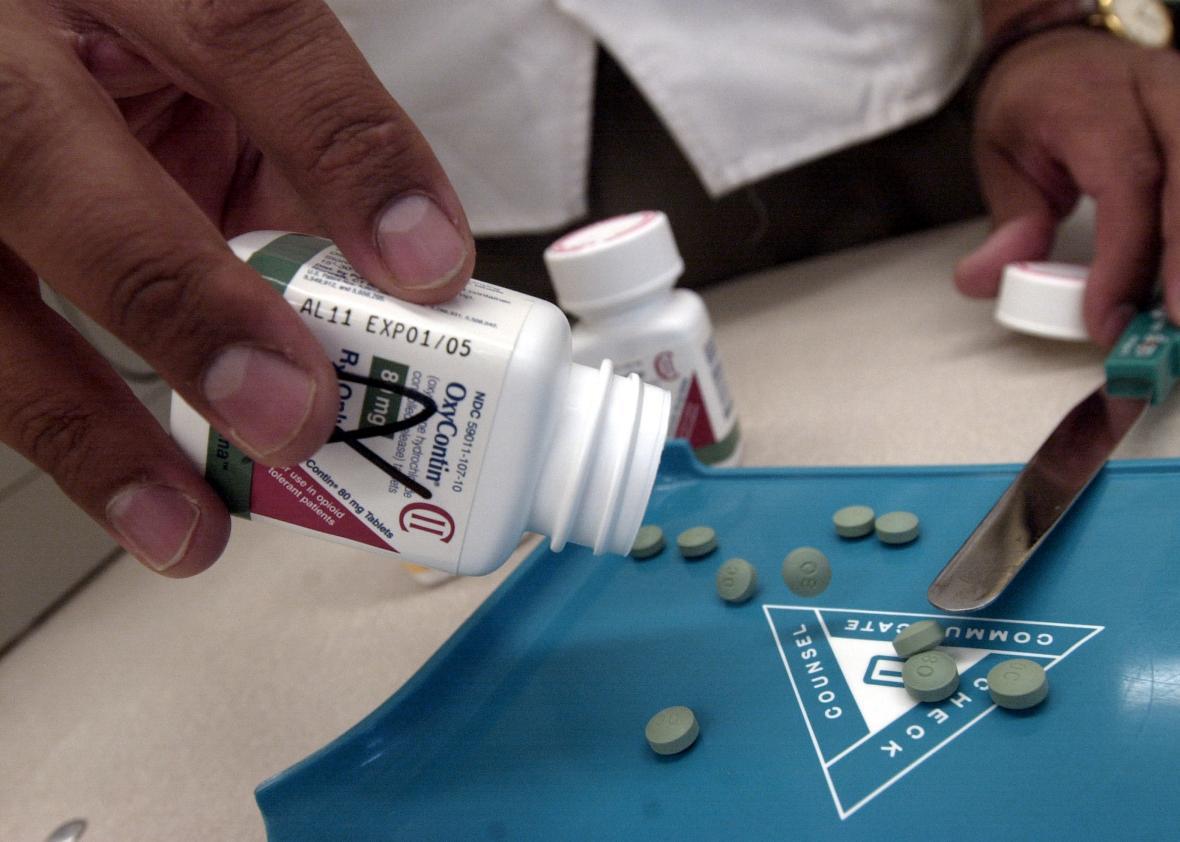

More and more middle-aged white Americans are addicted to heroin and opioids; it’s killing them.

On Monday, two Princeton economists published a study showing that middle-aged white Americans’ death rates are rising at alarming rates. (They compare the scale of the recent spike to the death rate for the same demographic from HIV/AIDS.) In a conversation with Slate, the study’s co-author discussed what’s behind the increase: suicides, alcohol-related liver diseases, and overdoses from heroin and opioids. The rise is particularly prevalent among whites with lower incomes and those with a high school education or less. This study reveals just how severe the nationwide heroin-and-opioid epidemic is, and how it affects debates over income inequality, the drug war, and mass incarceration.

Incarcerated people are expected to prove they’re remorseful about their crimes, but remorse is impossible to accurately detect.

Another recent academic paper questions the wisdom of sentencing people and granting probation or parole based on whether we think they’re sorry for what they did. As the paper’s author, DePaul law professor Susan Bandes, told Slate, there’s no evidence whatsoever that we can detect whether a person is remorseful or not by looking at them, nor is there evidence that people who are remorseful during a trial are less likely to commit another crime. Moreover, different judges in the study report contradictory signs of remorse. This has particular importance to death penalty cases, since a perception of remorse heavily influences whether or not defendants are sentenced to be killed. Bandes says that when the consequences can be so severe, instead of imagining defendants’ emotions, it might be better to admit that we just can’t tell.

At least we know the results of Election Day and how the Web feels about spooning.

- Tuesday was Election Day, and liberals took a beating, losing out to Texans irrationally afraid of transgender people and to those who fear racial integration of their schools, among others.

- There’s mounting evidence that a bomb, probably planted by ISIS or an ISIS affiliate, caused Saturday’s Russian plane crash in Egypt. Not good.

- Slate launched its new sleep blog The Drift with a manifesto against spooning. This enraged much of the Internet.

Nighty night,

Seth Maxon

Home page editor for nights and weekends