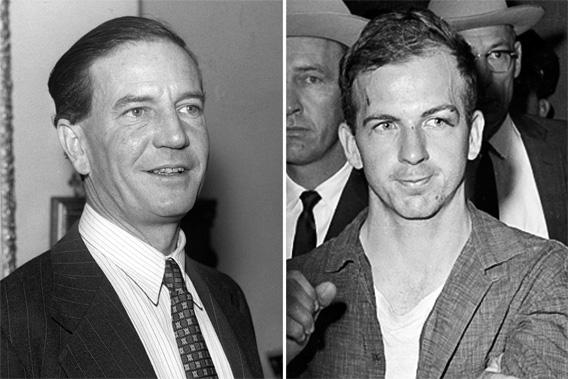

Oswald and Philby. Lee and Kim.

“The Lone Gunman” and “the Third Man.” We’re still haunted by the legacy of these spectral figures, their legacy of doubling and doubt—and, yes, the shadowy counterspy linked to both. At least I am. You should be too, since you live in a world of uncertainties they helped create.

Not just from their overt acts—Philby, long-term, high-level KGB mole inside British secret intelligence service (MI6), a double—or was it triple?—agent shaping the origins of Cold War paranoia; Oswald, leaving a legacy of mystery, paranoia and conspiracy theory around himself, of the sort that has come to shroud so much alleged certainty about historical truths ever after. Is there any major event that now doesn’t come with its penumbra of YouTube conspiracy fantasies? The more you look the less (undisputed) truth you see.

The two of them (and the shadowy third whose identity I will disclose, I promise) exemplify a century of double agents, double dealing, double meaning, doubly ambiguous doubt about the public narrative of history, ambiguities that cloud or complexify conventional wisdom about the accepted narrative and suggest we are lost in “a wilderness of mirrors.” And every once in a while something new turns up, a new twist, a declassified document, an overlooked defector, a forgotten witness.

As it has recently with both these enigmatic figures. A half-century after their defining moments on the stage of history, two new books have disclosed unexpected perspectives worth exploring.

1963: Fifty years ago, the year Kim Philby defected to Moscow, purportedly erasing any doubts he was a KGB mole. Although, in fact, the doubts persist in some circles, mainly in the form of theories that he was a triple, not a double, agent. That is, who was he really working for all those years, us or them? More piquantly: Is it possible even he didn’t know—that he had been set up and used? Questions too about exactly how he distorted the “facts” he communicated to both sides at the origin of the Cold War, thus shaping or misshaping history.

1963: Fifty years ago, Lee Harvey Oswald does something in Dallas, the president’s head explodes, and soon Oswald is dead too. According to polls, more than half the nation still believes that if Oswald was involved at all in the shooting (not just, as he claimed, “a patsy”) he was part of a conspiracy involving two shooters, even “two Oswalds” or an “Oswald impersonator” or two. But the true locus of mystery and generator of conspiratorial doubt is Oswald’s mind, that lonely labyrinth in which even he may have been lost. Whose side was he really on, was he a double agent, was he a player on his own stage, or was he being played? By whom?

I’ve spent a considerable amount of time exploring both enigmas. I thought that in my 12,000-word Philby investigation for the New York Times Magazine some time ago, I had exhausted the number of mysteries Philby set afoot with his double (or triple?) dealing. And I’ve written frequently on JFK theories, recurrently changing my mind on that morass of mystification; to my current belief Oswald was a shooter, though not ruling out the possibility of a second one, or silent confederates egging Oswald on to do the deed. But what an amazing legacy of paranoia he’s left us, what a vast spectrum of theories that seems to keep growing, concatenating.

Things seemed to have slowed down on that front, the high tide of conspiracy books receding (though not ceasing), the two camps—lone gunman vs. conspiracy—fortified in their opposing certainties with little or no new evidence on the crime itself emerging. I basically gave up thinking there would be anything new to emerge despite the likelihood that (as Jefferson Morley’s valuable investigative lawsuit claims) there are a large number of important documents on the case still classified.

But in the course of one week this winter I came upon two recent books that made me think the two cases deserve further thought.

A coincidence no doubt—as is the fact that the names of the authors of the two books—Lattel and Littell—are so similar (and end in the syllable for “tell”). In this game one has to learn to distinguish between the meaningful and the meaningless coincidences.

The Oswald-related book, Castro’s Secrets, is by Brian Latell, a former top-level CIA agent charged with the debriefing of a high-ranking defector from Fidel Castro’s highly secretive intelligence agency, the DGI. The defector who came in from the cold in Vienna in 1987, a guy named Florentino Aspillaga, offered some remarkable inside DGI information about Oswald, the DGI, and Fidel that, if true, argues for a paradigm shift in Kennedy assassination theories. He also discloses substantiating material from a previous defector—information that was new to me.

Courtesy of Thomas Dunne Books

The Philby book—Young Philby—is a unique (and strangely overlooked) historically-based spy novel by well-respected espionage writer Robert Littell (The Company and The Once and Future Spy among others, many of which suggest contacts within the intelligence community). It seeks to substantiate the possibility that Philby was more than a KGB mole, that in fact he may have served as a knowing or unknowing channel of information (and disinformation) for MI6 and the CIA—a theory I wrote about (and called “unlikely”) in my investigation, but which Littell—no naif in these matters—clearly seems to believe. And he says he has a smoking gun to prove it.

Maybe we should start from the beginning. Harold Adrian Russell “Kim” Philby, the Cambridge-educated scion of the British establishment, was the son of the once-famed Arabian explorer St. John Philby. According to most accounts, an Austrian sexologist and Soviet agent named Arnold Deutsch recruited Kim as a Soviet operative after he had left the leafy glades of Cambridge to consort with Austrian Communists (and marry one) during the 1934 street battles with fascists in Vienna. Philby’s mission: disguise himself as a right-winger and work his way up the old-boy network of the British ruing class on behalf of the NKVD (predecessor to the KGB). Kim was joined by a quartet of other like-minded college fellows later to be known as the “Cambridge Five.” If you’ve read your le Carré, you’ll recognize Kim as a good match in character at least for the mole, Bill Haydon, in Tinker, Tailor.

And boy did he succeed, getting recruited by an apparently oblivious (or were they?) MI6 as the second world war began, ending up after the war as the head of MI6’s Russian Division, thus making him the grand pivot man in the genesis of the Cold War—confirming Stalin’s belief in the evil plotting of the West, feeding the West a careful diet of disinformation about what the Soviets were up to. Or was it the other way around? Who got the info and who got the disinfo? Should we credit Philby and his other moles with preventing World War III—giving Stalin the security that his most paranoid fears (of a surprise nuclear attack) were unfounded, because he would have known from his moles if something was up? Or did both sides get what Philby chose to weave out of his own history-making imagination? (“Espionage,” le Carré once wrote, “is the secret theatre of our society.”)

Ultimately Philby was on the verge of becoming head of MI6—as I believe I was the first to confirm from a highly placed source—when the “Third Man” affair fatefully killed his chances. Two of the Cambridge Five defected to Moscow in 1951, fearing they were about to be arrested, and suspicion fell on Philby for being the “Third Man” who tipped them off. Philby was forced to resign and consigned himself to a purgatorial limbo in the Middle East where, under the watchful eyes of MI6, the KGB, and the CIA, he wrote for the U.K. Observer (and the New Republic, which was owned until 1956 by another former Soviet mole Michael Straight, not yet exposed). It should be noted that the famous Orson Welles-starring film The Third Man was written by Graham Greene and released in 1949, two years before Philby was named “Third Man.” (Click here for more on the Graham Greene connection.)

Finally in 1963, MI6 felt it had enough evidence Philby had been a mole to confront him in Beirut. In what is still one of the most debated episodes in his career, he managed to—or was allowed to—escape to Moscow, where he lived until his death in 1988. Still, even in Moscow he was never fully trusted, according to former KGB colleagues I interviewed. As far back as 1948, an NKVD agent was compiling a dossier on Philby, attempting to prove that he was really a plant — not a double but a triple agent actually working for MI6 to deceive the Soviets into thinking he was their mole. One ex-KGB source called this 1948 hellhound on Philby’s trail “Madame Modrjkskaj,” said to be head of the NKVD’s British division, who “came to the conclusion that Kim was a plant of the MI6 and working very actively and in a very subtle British way.”

Here’s where Robert Littell’s new novel takes up the case. The somewhat misleadingly titled Young Philby tells the Philby story in part from the point of view of a female NKVD analyst whose name Littell spells “Modinskaya.” (I think the spelling is just a variant, not an attempt to fictionalize her.) And basically Littell’s novel concludes that she was right: that, yes Kim—encouraged by his scheming father, St. John Philby—was playing the triple-agent game on behalf of MI6. Littell (who did not respond to an email sent through his publisher to his residence in France) portrays Madame M. as being executed by Stalin for her suspicions of his prized mole, although I don’t know if this is historically based. But if she died, suspicions of Philby never did, and they haunted him even in his post-defection home in Moscow.

But what makes Littell’s book more a than just another twisty spy fantasy is the nonfiction epilogue, in which Littell tells of a fascinating encounter he had with Teddy Kollek, a figure most well-known as longtime mayor of Jerusalem, but who knew Kim as a young communist sympathizer in Vienna in 1934. And here’s where we meet our mysterious third figure: in a 1983 Harper’s piece I wrote about the way there were some who believed U.S. counterintelligence guru James Angleton had not been fooled by Philby, because Angleton had been tipped off by Kollek and—here’s yet another way of looking at the case—had deliberately fed Philby disinformation. Philby was then the dupe of Angleton, not the other way around. An unwitting triple agent.

People are prepared to believe that of Angleton because of his mythic reputation within the intel community as the Master of the Game—a reputation he guarded jealously. If Philby was, as many have called him, the spy of the century, James Angleton was the counterspy of the century. Legendary for having learned the complexities of the game from the study of “seven types of ambiguity” as a Yale English literature scholar—he published High Modernists such as William Carlos Williams and Ezra Pound in his undergraduate literary magazine—he was notorious for pursuing suspicious ambiguities in the backstories of many defectors he believed were actually KGB plants. He would want to have people believe he was outfoxing Philby, not the other way around.

Photo by AP

Of course that whole line of thought could have been disinformation spread by Angleton to discredit Philby with Moscow and make himself look like the Master of the Game, when most (including myself and Cleveland Cram, the CIA’s official historian of the mole war within the agency) believe that Philby’s deception drove Angleton crazy with paranoia about potential moles, so crazy that he tore the CIA apart and discredited legitimate suspicion of moles—thereby allowing the real damaging one, Aldrich Ames—who joined after Angleton left—free rein. Are you with me? Don’t worry, I find that even getting lost in this bewildering thicket is illuminating about the way this world works.

In his nonfiction epilogue to Young Philby Littell focuses on a story Teddy Kollek told him about Philby and Angleton shortly before he died in 2007. A significantly more detailed story of a Kollek tip-off than has been seen before, a story about how before the “Third Man” accusation in 1951 Kollek visited Angleton at CIA headquarters in Washington.

Philby was then serving as MI6’s liaison to the CIA, downloading all its secrets to the KGB via an unknowing Angleton, a regular lunch companion of Kim. Or was he? Here’s the money quote from Kollek, according to Littell:

“I was walking towards Angleton’s office … when suddenly I spotted a familiar face at the other end of the hallway … I burst into Angleton’s office and said ‘Jim, you’ll never guess who I saw in the hallway. It was Kim Philby!’ And I told him about Vienna … and the suspicion that Philby may been recruited … as a Soviet agent. … And I said ‘Once a Communist, always a Communist.’ ”

Littell says he asked Kollek how Angleton reacted. “No, Jim never reacted to anything. The subject was dropped and never raised again.”

Wow. This is a great moment on the stage of the secret theater. Did Angleton know and pretend he didn’t know? Did he not know and pretend he did? Or did he not believe and pretend he did or … well you figure out the permutations. Angleton must have run through them at warp speed and decided to leave Kollek—and the rest of us—in eternal doubt. Because if he knew and let on to anyone he did then he couldn’t be sure he could play Philby the way he might have wanted to.

I believe, as they say, the truth is out there. I don’t believe truth is relative or perspective-dependent or that there’s more than one truth. But I also believe the truth is sometimes elusive, terminally ungraspable. Now that we know Angleton heard Kollek’s direct suspicion of Philby, we know he had to have made a decision. But we may never know what that decision was. It might have been something he led certain acolytes to believe after Philby’s defection, to maintain his reputation as all-knowing counterspy. Or it may have been too explosive a truth to trust to anyone but himself. But maybe not. Our chances of knowing it may have died when Angleton did in 1987. The truth is out there, but it may be buried forever.

Angleton’s silence and apparent failure to act: Was it a failure of judgment, a dereliction of duty, or evidence he was playing a deeper game? One CIA analyst even wrote a massive report suggesting Angleton himself was a mole. If you leave aside for a moment the fact that people died because of Philby’s treachery—whichever side he was on—it’s all so deliciously complicated, way beyond le Carré.

And there he is again, Angleton, who, turns out, plays a crucial role in Brian Latell’s new Castro/Oswald book as well. Because while Castro’s Secrets centers on Latell’s firsthand account of debriefing Aspillaga, the 1987 DGI defector (whom he interviewed in depth), Lattel also has dug up files on a previous defector who was inside the Castro’s DGI at the time of the Kennedy assassination and defected in early 1964, while the Warren Report—which concluded that Oswald acted alone—was being written. According to Latell, the 1964 defector claimed the DGI had significant contacts with Oswald, but that Angleton mysteriously suppressed the defector’s report on what Castro might have known, denying the Warren Commission any knowledge of it.

Courtesy of Palgrave Macmillan

Both of the previously undisclosed DGI defector reports center on a highly contentious episode two months before the assassination of JFK, when Oswald visited the Cuban Embassy in Mexico City and demanded a visa to Cuba—supposedly to fight for the Cuban Revolution then under threat from invasion and assassination plots orchestrated by JFK and his brother Bobby. Or was it an Oswald impersonator who visited the Cuban Embassy? The notorious “second Oswald,” or one of the second Oswalds as conspiracy theorists have argued? The conspiracy paradigm, which has guided skeptics of the “lone gunman” theory for a half-century, has it that we ought never to take Oswald at his word that he was a fanatic follower of Castro; instead we must believe this image of Oswald was made up or set up (by an impersonator) so that the JFK kill could be pinned on a Commie—thus justifying for anti-Castro Cubans or the Mafia or the CIA (or whoever really did the hit) a retaliatory final invasion to overthrow Fidel.

Latell’s new information undermines this farfetched-sounding but widely accepted view. Latell’s view is such heresy that one of the most intelligent and knowledgeable lone-gunman skeptics I know told me he refused to read Latell’s book. He said he’d caught Latell in a misquotation in some review of the book and that was enough for him.

I probably don’t have to fill you in much about Oswald. The sociological obverse of Philby: No Cambridge grad, Oswald was New Orleans born and spent a difficult youth in the Bronx. The only salient detail we know about his youth is that he liked to watch the TV show I Led Three Lives, about an FBI man who goes undercover to investigate Red subversion plots. A mole! As a Marine, Oswald just happened to be stationed at a U-2 base in Japan; he subsequently defected to the Soviet Union, declaring himself a true believer in Communism. The defection has long been a source of much speculation: Had he been “planted” there by our side? The way Philby was suspected of being a plant?

Oswald’s usually portrayed as a dumb patsy, loon, or tool, but he was onto the whole mole game from the get-go from that TV show. A subject of conspiracy theories, yes, but maybe a deliberate manipulator of the mystification that would surround him. Smarter than most give him credit for, in his black sweater he looked and sometimes sounded like a twisted Lenny Bruce.

The KGB had its doubts about Oswald, or so it appears: They settled him in out-of-the-way Minsk, where he married a young Russian named Marina. They bugged his apartment for years. (Norman Mailer and Larry Schiller got the tapes which are, alas, fairly mundane.)

Then he decided to re-defect to the U.S. (Was he going back because he was disillusioned by Communism, or because the KGB sent him on a mission?) He settled in Dallas, but in the summer of ’63 moved on his own to New Orleans, where he advertised himself as a pro-Castro activist and got into fights with anti-Castro Cubans. (Was he making himself conspicuous as a Communist in order to pin the forthcoming crime on Castro or the Russians?)

It was Oswald’s trip that fall to Mexico City that is the hot center of Lee Harvey conspiracy theory. And Latell now comes forward with two defectors from the DGI to say Oswald had extensive contacts with Fidel’s intel men in Mexico City, even cites a report Oswald vowed to kill Kennedy, and that Fidel knew of those contacts.

In other words Fidel may have had—Latell is not definitive but strongly suggestive of it—foreknowledge of Oswald’s motives, if not complicity in the Dallas hit. Latell’s attention-getting revelation: According to DGI defector Aspillaga, on the morning of Nov. 22, 1963, the DGI was ordered to shift radio surveillance from South Florida, where the Cuba exiles were habitually scheming, to Texas, where JFK was touring in an open car. You do the math.

I did, and it still doesn’t quite add up to me: I don’t consider this shift in surveillance decisive because Castro or the DGI may just have wanted to make sure they didn’t miss a word JFK had to say at this high point in tensions between Cuba and the U.S. Daggers were drawn: That very morning in Paris, Nov. 22, a top-level CIA agent was handing a poison fountain pen to a man he thought was a CIA mole. The man, part of Castro’s entourage, was supposed to use it to inject Fidel with a deadly toxin. I’m not making this up, and it makes sense when put in the light of the almost unbroken record of CIA blunders to this day. Because the fountain pen assassin was actually a triple agent (see, they exist!) working for Fidel and the DGI and told them all about this idiot murder plot. A fact long-rumored but substantiated by Aspillaga, Latell’s defector. And—according to Latell—a putative motive for Castro to hit JFK or allow a hit plan to go forward. Though Fidel denied it, repeatedly, Aspillaga insists Castro was lying at the very least about his knowledge of Oswald activity at the Cuban Embassy, and his pro-Castro allegiance.

And in the midst of all this we once again find James Angleton, whose counterintelligence staff in the aftermath of the assassination was sending questions to the 1964 DGI defector who claimed the DGI had extensive contacts with Oswald “before, during, and after” his Mexico City trip. But Angleton never shared this potentially crucial information with the Warren Commission.

Which leaves the question: Why did Angleton withhold this potentially crucial information from the Warren Commission investigators? Was he thinking where it might lead? The big fear among many, including new president Lyndon Johnson and Chief Justice Earl Warren, was that we would discover an explosively dangerous truth, a truth that could lead to a third world war. Latell comes out and echoes that fear, which was not out of the question. If it had been found out then that the KGB or the DGI was complicit in the Kennedy kill, we may well have been provoked to invade Cuba, leading—Latell speculates—to a clash with the Russian troops still stationed there, leading to … who knows. If it were true, nobody, including apparently Angleton, wanted it known. The price of revenge might be too high.

Nonetheless, over the years the Angleton loyalists in the intelligence community and the press have leaked provocative bits from the Master suggesting the KGB or the DGI was behind the JFK assassination. Indeed, Edward J. Epstein, whose reporting on Angleton has been the most extensive of anyone, comes out and declares, in his new book The Annals of Unsolved Crimes, that “my own assessment is that Cuban intelligence had influenced, if not directed, Oswald’s actions”—a judgment based in part based on Latell’s revelations. “We now know,” Epstein writes, “that Castro had the most powerful of all motives: self-preservation. … Castro ascertained that the CIA was actively planning to assassinate him [and that] the plot appeared to have the backing of JFK himself.” I don’t believe the evidence available allows such a definitive conclusion, but it is a thought-provoking heresy.

Will the Latell book (and Epstein’s conclusion) cause a rethink of the dominant assassination conspiracy paradigm? I wish I could say or Latell could tell, or Littell will tell. I think Angleton knew more than he would tell. (He knew about the poison fountain pen plot, for instance.) But both stories point to crucial unresolved questions that still trouble our national soul, inflection points in the Cold War politics that got us where we are but could have led to nuclear conflagration.

Angleton himself once said something typically cryptic to me along those lines in a telephone call. When I asked him to discuss details of the past after he’d left the CIA, he told me he couldn’t because “the past telescopes into the future.” Or was it the future telescopes into the past? Now I’m not so sure.