Henry Louis Gates was just trying to get into his house.

It was July 16, 2009, and the prominent Harvard scholar of black history had returned from a trip to China to find that the door of his Cambridge, Massachusetts, home was jammed. He opened the door with the help of his cab driver and had been inside for several minutes when police Sgt. James Crowley arrived to investigate.

It’s at this point that we enter a Rashomon moment.

According to Gates’ account of the encounter, provided by his lawyer Charles Ogletree, Crowley asked him to step outside the house. Gates refused and asked why. Told that the officer was investigating a break-in, Gates replied that this was his house; asked for proof, he produced his driver’s license and Harvard identification. At this point, Gates said, he asked Crowley for his name and badge number. Crowley didn’t respond and left the house. Gates followed onto the porch, at which point Crowley arrested him on a disorderly conduct charge. “Thank you for accommodating my earlier request,” Crowley said.

Crowley tells a different story. In his police report, he wrote that he arrived at the home after a white female observer had called the police to report an attempted burglary, having watched two black men force open the door to the house. Gates, wrote Crowley, was hostile and uncooperative, immediately charging him with racism: “Why, because I’m a black man in America?” Crowley said he believed Gates but was taken aback by the professor’s behavior, which included threats and continued charges of racism. Crowley said he was leaving the house and asked Gates to step outside if he wanted to continue the conversation. Gates came outside and continued to yell, prompting Crowley to issue a warning and then make an arrest.

If this were the whole story—two conflicting accounts of a simple misunderstanding that escalated into something worse—it would be a footnote in the story of the past 20 years. But the arrest of Henry Louis Gates would become a kind of inflection point in public opinion, both setting the stage for discussions of race and racism during the Obama administration and highlighting the kinds of racial divisions that have culminated in the rise of Donald Trump and that may well dominate our politics for the foreseeable future.

But first, back to the story. A week later, during a press conference on health reform, Barack Obama was asked about Gates’ arrest. The president, in just the seventh month of his first term, gave a forthright response:

I don’t know, not having been there and not seeing all the facts, what role race played in that. But I think it’s fair to say, No. 1, any of us would be pretty angry; No. 2, that the Cambridge police acted stupidly in arresting somebody when there was already proof that they were in their own home. And No. 3, what I think we know separate and apart from this incident is that there is a long history in this country of African-Americans and Latinos being stopped by law enforcement disproportionately. That’s just a fact.

Obama wasn’t wrong. It was just a fact that Gates’ arrest evoked a long and painful history of unfair treatment. But Obama was supposed to be beyond race. By evoking past discrimination, he disturbed that fantasy. Immediately, because of his comments, the arrest of Gates went from minor kerfuffle to an issue of national discussion. Police groups spoke out, accusing the president of worsening relationships between communities and police departments. Likewise, Republican lawmakers called on Obama to apologize to Sgt. Crowley. Within a few days, the president had called Crowley to invite him and Gates to a meeting in order to hash out their differences.

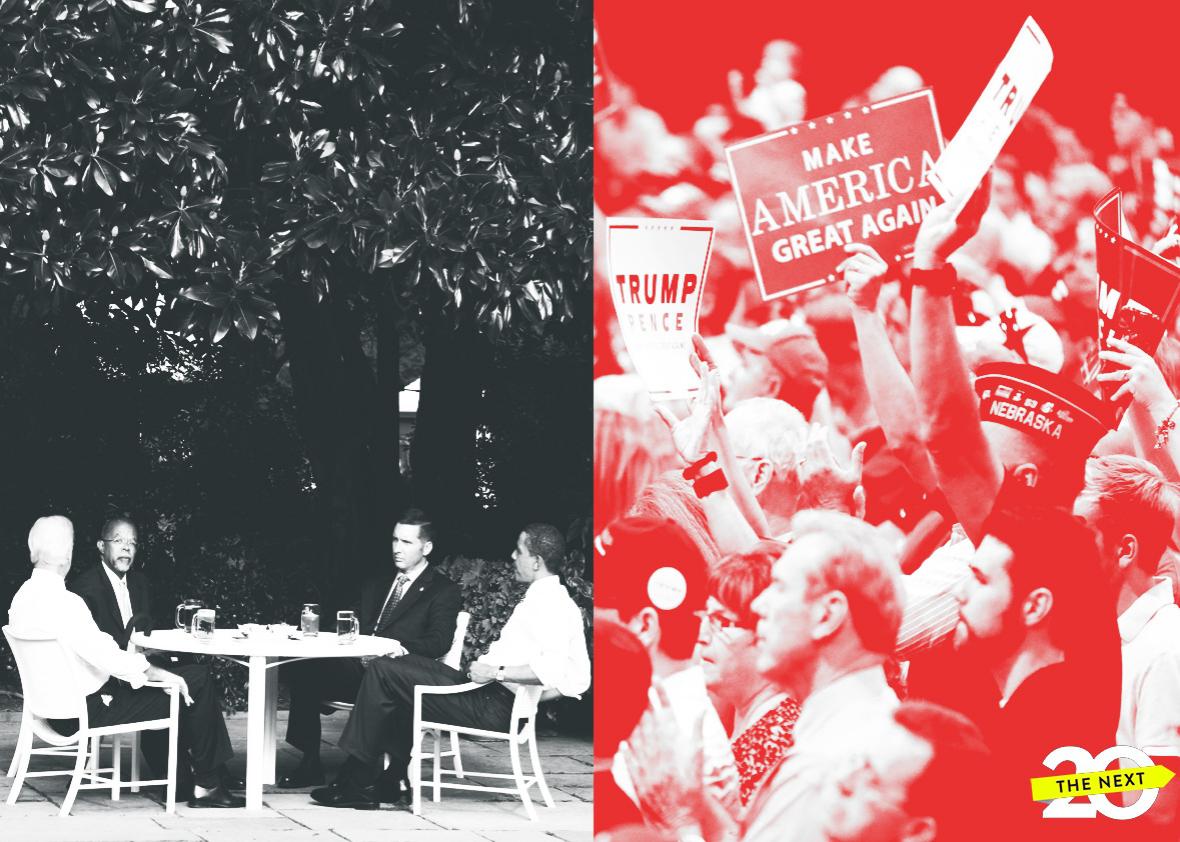

Two weeks after Crowley arrested Gates, the two met with Obama and Vice President Joe Biden in a “beer summit” in a courtyard near the Rose Garden. The meeting, according to Gates, was amicable. “We hit it off right from the very beginning,” Gates said in an interview with the New York Times. “When he’s not arresting you, Sergeant Crowley is a really likable guy.”

Gates and Crowley came to an understanding. There wasn’t such a clean wrap for President Obama. His comments on Gates’ arrest, and the backlash from police and their political allies, marked the start of a long slide in public opinion. But this wasn’t a general decline. No, the Gates arrest was the first major blow to Obama’s standing with white Americans.

Before Obama’s comments, 53 percent of whites approved of his job performance, according to the Pew Research Center. After, this slipped to 46 percent. Forty-five percent of whites surveyed disapproved of how Obama handled the situation. Gallup polling, likewise, shows a significant decline in white support for Obama, beginning in this period. In fact, Obama would never be as popular with white voters as he was just before the Gates affair. On the eve of Gates’ arrest, according to Gallup, 51 percent of whites approved of Obama. Afterward, that fell to 46 percent. Today, just 40 percent of whites approve of the president, even as his overall job approval pushes past 50 percent.

Now, these polls were compounded by external conditions. The economy was still struggling from the shock of the Great Recession, the president’s health care bill was sharply divisive, and the public was fatigued by battles in Congress between the Democratic majority and an implacable Republican minority. But the picture is clear: When Obama spoke out about Gates, white Americans began to tune him out.

You can attribute some of this to the fact that Obama stood on the other side of a police officer, and for white Americans, police are among the most trusted of all groups in society. But it’s also important to look at the racial dynamics of the time. In 2009, millions of Americans were still caught in the heady daydream of “post-racial America,” sustained by a president who was black, but who wasn’t quite a black president. Fifty-three percent of Americans, according to a Pew survey, said that the country was “making ground” on racial discrimination. Obama’s observation—that black lives still faced unfair treatment—was an abrupt challenge to that idea, and it brought a backlash.

Obama backed off of his comments. “I could’ve calibrated those words differently,” he said, the next day. The sharp and furious response to Obama’s remarks would shape his approach to race for the rest of his first term. University of Pennsylvania researcher Daniel Q. Gillion found that Obama spoke less about race in his first term than any Democratic president since John F. Kennedy, and there’s no question that the Gates incident played a part. From then on, Obama would shy away from racial dispute, demurring from controversy and trying to situate himself as a president who happens to be black, not a black president. For most of his first term, Obama was silent on police killings of unarmed black Americans, silent on controversies like the execution of Troy Davis, and even silent on the obvious racism behind demands for his “long form” birth certificate.

This would end, in dramatic fashion, in July 2013, four years after the Gates incident and just after George Zimmerman was acquitted in the death of Trayvon Martin. This time Obama didn’t shy away from discussing race head on. “You know, when Trayvon Martin was first shot I said that this could have been my son,” said Obama. “Another way of saying that is Trayvon Martin could have been me 35 years ago. And when you think about why, in the African American community at least, there’s a lot of pain around what happened here, I think it’s important to recognize that the African American community is looking at this issue through a set of experiences and a history that doesn’t go away.”

It’s hard to say exactly why Obama changed course. There’s no doubt that the president was personally affected by the killing of Trayvon Martin and other young men, like Jordan Davis (they are partial inspiration for his chief philanthropic project, My Brother’s Keeper). At the same time, political circumstances had changed. Not only was Obama in his second term—and thus freed from the pressure of re-election—but his legislative agenda had stalled, turning his attention to other issues and concerns, and giving him some space to speak on controversial matters. And outside of the world of presidential politics, newly galvanized activists were pressing the White House for action on criminal justice reform, opening further space for rhetoric and action.

The Gates arrest, and Obama’s reaction to it, did more than shape the president’s behavior. It shaped a template for how Americans would talk about and experience controversies around race and policing—at precisely the time when those controversies would move to the forefront of American consciousness. Saturated coverage—complete with audio, video, and pictures—would help polarize Americans along racial and ideological lines, between those who could sympathize with the police and those who couldn’t, between those who experienced discrimination and those who didn’t. And so, when Martin was killed—for example—millions of Americans saw him as an innocent teenager, and millions more pictured him as a dangerous thug. Rinse and repeat for Michael Brown, for Jordan Davis, and even for 12-year-old Tamir Rice. Just this week, Tulsa, Oklahoma, police shot 40-year-old Terence Crutcher, deemed a “bad dude” just before he was killed.

The Gates controversy represented, in microcosm, a deep divide between black and white Americans on the reality and ongoing existence of racial discrimination. Polling around the event revealed broad disagreements among blacks and whites about discrimination and law enforcement. Seventy-six percent of black Americans said blacks do not receive equal treatment from the police, according to a post-arrest poll from ABC News and the Washington Post. Just 34 percent of whites agreed. Twenty-nine percent of whites blamed Gates for his arrest.

In 2016, as police discrimination against black Americans has become the flashpoint of a new civil rights campaign led by the Black Lives Matter movement, and as the steady drumbeat of deaths at the hands of police continues, the divide we saw in 2009 still exists. Thanks to greater visibility for the issue, somewhat higher percentages of both blacks and whites recognize police discrimination against blacks. But the opinion gap between blacks and whites on the issue remains enormous.

Given Donald Trump’s rise as a formidable political figure, with a real path to the White House, the divide seems in many ways greater and more unbridgeable than it did seven years ago. Trump, who came to political prominence as an advocate for anti-Obama conspiracy theories, is the embodiment of a specific white reaction against claims for greater economic and social equality between whites, blacks, and other marginalized groups. The polarization and disagreement that flared with the Gates controversy has curdled into a resentment that threatens America’s status as an open-minded, pluralistic democracy.

The racial grievance of the Trump movement isn’t new. It was present in the backlash to Obama’s comments, just as it is present in the backlash to Hillary Clinton for describing the bigotry of many Trump supporters. Put simply, if the reaction to Obama and Henry Louis Gates showed the great degree to which this wasn’t a “post-racial” country, then the fate of Trump—just six weeks away—will reveal whether our country has actually made any progress at all.