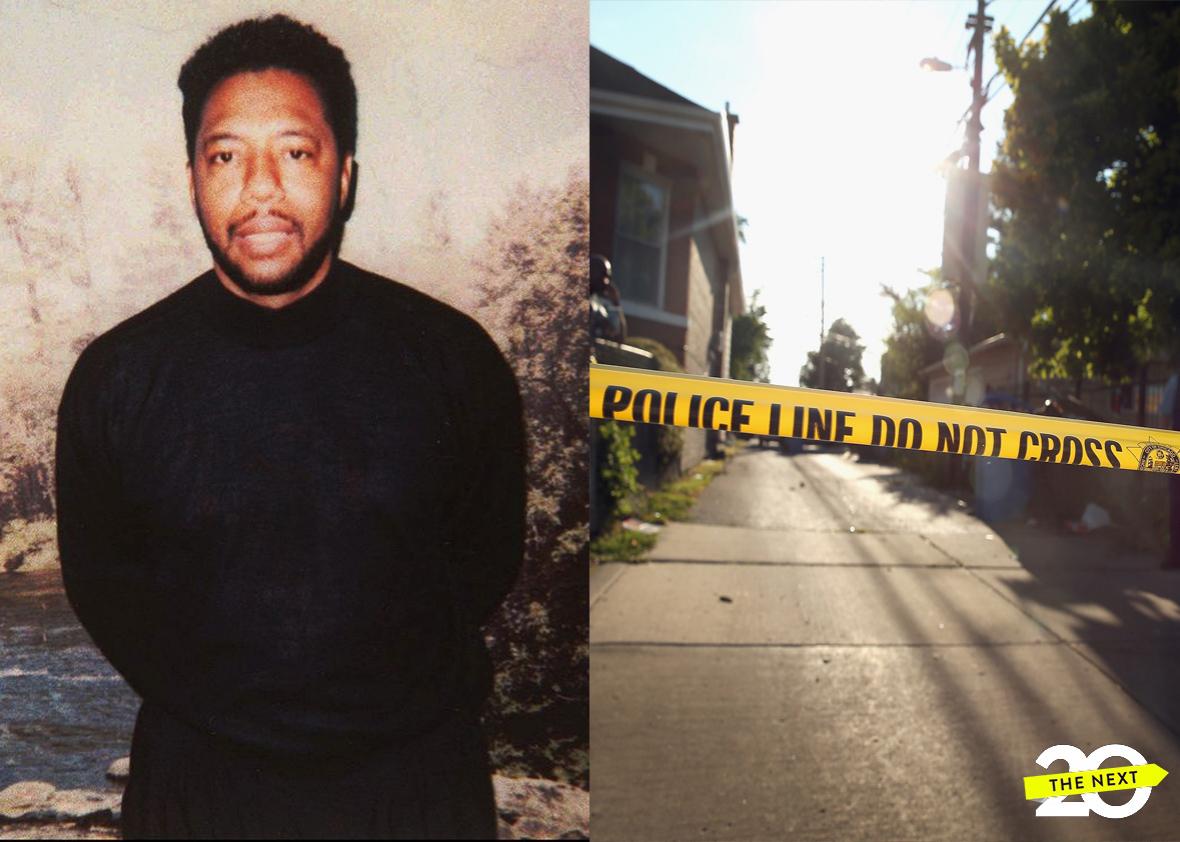

Ronald Safer didn’t know all that much about gangs when, in 1992, he was assigned to lead a federal investigation of Chicago’s Gangster Disciples, the notorious street gang led by kingpin Larry Hoover. Safer, a prosecutor who had joined the U.S. attorney’s office in Chicago after years working in private practice, was warned that he’d be taking on a mighty organization—a powerful commercial enterprise that, alongside a handful of other sophisticated gangs, all but controlled Chicago’s illegal drug trade.

Hoover’s empire was reputed to comprise 30,000 members across the country, and prosecutors believed it was bringing in as much as $100 million a year in drug sales. Worse, the gang was suspected of being responsible for hundreds of murders in Chicago since the 1980s, when the crack epidemic turned the organization into a juggernaut willing to kill for territory.

The GDs were feared and even respected; one Chicago-based Drug Enforcement Administration agent marveled at their extreme discipline and training, and said they might be the “largest and most successful gang in the history of the United States.” Hoover, in particular, was viewed in Chicago as a “mythic figure” and drew comparisons in the press to Al Capone. But when Safer toured the neighborhoods where the GDs reigned, what he saw were open-air drug markets operated almost entirely by children.

“Whether they were 16 or 18 or 14 or 20, I don’t know. But they were young. They were very young. And it seemed to me there was an endless supply of them,” Safer told me recently. “These were the people who were out there to be arrested—the gang leaders put those kids out there to be arrested, and to be shot at. It struck me that they were as much the victims of gangs as the people in the community.”

Up to that point, Safer said, the Chicago Police Department had mostly been fighting the Disciples by arresting these young cogs in the machine—easy targets who, unlike Hoover and his circle of high-ranking lieutenants, could be directly linked to the drugs they were selling and the illegal guns they were using to defend the gang’s turf. Safer wanted to try something different. He wanted to take down the guys who were actually in charge.

Operation Headache, as it was known internally, first bore fruit in the summer of 1995, when Safer and his team secured indictments against 38 higher-ups in the Gangster Disciples organization. Among them was Hoover, who had been running the gang from prison while serving a 150- to 200-year sentence for murder since 1973. (Investigators obtained evidence of his active leadership of the GDs by secretly recording conversations he had with his lieutenants during in-person prison visits.)

The first wave of convictions stemming from Operation Headache came in March 1996. But the biggest, most symbolically meaningful blow to the Gangster Disciples was delivered in May 1997, when Hoover was convicted of 42 counts of conspiracy to distribute drugs, received a sentence of six life terms, and was transferred to a supermax prison in Colorado, where his cell was located several stories underground and his ability to communicate with the remnants of his gang were severely constrained. Soon, the GDs in Chicago had been all but neutralized, and the authorities shifted their attention to decapitating the city’s other major drug organizations, the Black Disciples and the Vice Lords.

Over the course of a roughly 10-year stretch starting in the mid-1990s, leaders from the GDs, the Vice Lords, the Black Disciples, and to a lesser extent, the Latin Kings were successfully prosecuted and taken off the street. The top-down assault appeared to work as Safer and his colleagues had hoped: violent crime in Chicago began to decline, with the city’s murder total dropping from a high of 934 in 1993 to 599 10 years later.

For a while, it looked like the trend might continue moving in a positive direction, but after dipping below 500 in 2004, the number of murders in Chicago per year leveled off and began hovering in the 400s. Over the past several years, however, the situation started getting worse; today, Chicago is once again synonymous with out-of-control gun violence, a city that regularly makes national news for the perilous existence that some of its poorest residents must endure. Over the weekend of Sept. 12, the city passed 3,000 shootings and 500 murders since the beginning of the year, surpassing in just nine months the total numbers from 2015. As of this writing, the 2016 tally is up to 3,131 shootings and 530 homicides; a recent report from the Brennan Center for Justice showed that Chicago, by itself, is responsible for half of the 13 percent increase in homicides that the country as a whole is projected to experience this year.

According to the Chicago Police Department, 85 percent of the city’s gun murders in 2015 can be attributed to gang violence—a statistic that suggests a return to the bad old days while obscuring how profoundly the nature of Chicago’s gang problem has changed in the intervening years. While experts say the Latin Kings, a Hispanic gang, continue to run a large and rigidly organized drug-selling operation on Chicago’s West Side, the majority of Chicago residents who call themselves gang members are members of a different type of group. Rather than sophisticated drug-selling organizations, most of the city’s gangs are smaller, younger, less formally structured cliques that typically lay claim to no more than the city block or two where they live. The violence stems not from rivalries between competing enterprises so much as feuds that flare up with acts of disrespect and become entrenched in a cycle of murderous retaliation.

Many close observers of Chicago’s violence believe that, as well-intentioned as it was, the systematic dismantling of gangs like the Disciples led directly to the violence that is devastating the city’s most dangerous neighborhoods in 2016. Taking out the individuals who ran the city’s drug trade, the theory goes, caused a fracturing of the city’s criminal underworld and produced a vast constellation of new entities that are no less violent, and possibly even more menacing, than their vanquished predecessors.

“Every time they hit these large street gangs, they’d focus on the leadership,” said Lance Williams, an associate professor at Northeastern Illinois University, and the co-author of a book about the rise and fall of the Black P Stone Nation, a gang that was eradicated in the 1980s. “It’s like cutting the head off a snake—you leave the body in disarray and everyone begins to scramble for control over these small little areas. And that’s where you get a lot of the violence, because the order is no longer there.” Williams added: “When you lose the leadership, it turns into chaos… What we’re dealing with now is basically the fallout of gang disorganization.”

The proliferation of small gangs has created a complicated and ever-changing patchwork of new alliances and rivalries, and instilled in many young people—predominantly poor, black men—a sense that they are vulnerable at all times to lethal attacks by members of opposing factions. The BBC captured this sense of constant fear and anxiety in a recent documentary about the violence in Chicago: Throughout the short film, the young men who are its subject are visibly on guard for rivals.

“It used to be there were fewer gangs but they were more pronounced—it was not the smaller, what I call ‘splinter’ groups that have formed since,” said the Rev. Walter Johnson, who was the pastor of a church serving the now-demolished Cabrini Green neighborhood throughout the 1990s. “In recent history it’s been just all-out war amongst everybody. In some places, I’ve noted that on one block, three or four different factions are warring against each other.”

Veterans of ’90s gang life in Chicago note that the imperative to generate revenue through drug sales created an incentive within the old gang “nations” to avoid the police scrutiny that came with violent crime. This meant that junior members weren’t allowed to settle their disagreements with gunfire unless they had permission from their elders. “We had it so that an individual had to deal with two words in his vocabulary and his way of life: accountability and consequences,” said Wallace “Gator” Bradley, a former member of the Gangster Disciples who now runs an organization called United in Peace Inc. “Before an individual picked up that gun, those two words were implanted in his mind.”

Today, experts say, the crews that have replaced gangs like Hoover’s are driven by goals less tangible than money, and the conflicts that erupt between them are more often provoked by interpersonal conflict than disputes over drug territory. “Back then, if there was violence, they were fighting over something—they were fighting over drug turf,” said Bradley. “The violence you’re seeing now, it’s almost attitude-driven.”

“Drug money is a small percentage of the killing now,” said Tio Hardiman, one of the original members of the violence-prevention organization featured in the 2011 documentary The Interrupters. “The killing now is all about reputation, disrespect, revenge, and robbery. That’s what the killings are all about now. They’re not building no nations.”

* * *

There is an undeniable logic to the theory that today’s gang crisis in Chicago is the product of yesterday’s attempt at a solution: Having shattered the commercial structures that imposed order from above and made clear to would-be kingpins that taking on leadership positions in criminal enterprises would invite aggressive prosecution, the city’s law enforcement community is now looking at a messy, vicious war between the dangerous shards.

There are other factors, however, that this simple equation obscures. For one, it’s hard to separate the impact of the gang crackdown from the demolition of the city’s public housing projects, which scrambled and disrupted gang affiliations during the 1990s by relocating people who once lived among friends and allies into neighborhoods where they found themselves surrounded by strangers and enemies. Second, it’s crucial to remember that, as bad as the violence in Chicago has gotten, there were more people being murdered in the ’90s than there are now. Insofar as gang leaders had the power to keep their underlings in line and prevent them from committing senseless—or at least bad-for-business—acts of violence, they did not exercise it liberally.

“If we’re just purely looking at the numbers, and we’re making the argument that things were better when we had structure, it just doesn’t hold,” said Andrew Papachristos, an associate professor of sociology at Yale University and the author of a forthcoming book about the rise and fall of the Gangster Disciples. “There’s just no evidence to suggest that’s actually the case.” Maybe there were penalties for killing someone without a leader’s blessing, Papachristos added. “But what were the penalties? More violence.”

The violence could take many forms. There was a fascinating moment during the first trial of the Gangster Disciples, when the defense put on the stand one Rev. T.L. Barrett Jr., a pastor at a South Side church whose house had been vandalized when someone threw bricks through his window. The priest testified that leaders from the Gangster Disciples had resolved the matter by tracking down the culprits—a pair of teenagers—and forcing them to get on their knees in the pastor’s living room and apologize to him. The takeaway from the story was supposed to be that the GDs—whose defense at trial relied on the idea that they had morphed from a violent drug gang into a politically legitimate force for good in the black community—were a kind of glue that held Chicago’s most impoverished neighborhoods together.

It was true that Hoover used his influence to some positive ends—through a political action committee, he had organized voter drives and marches for better schools and health care—but in his cross-examination of the pastor, Ron Safer sought to shift the emphasis, showing that while the Gangster Disciples surely had the power to maintain order, it was a power rooted in the threat of violence and coercion, and fueled by a drug business that depended on the misery of desperate people. As Nicholas Roti, the former head of CPD’s Bureau of Organized Crime, put it in an interview in 2013, “If [people] actually believe that having an anti-social career criminal in control of thousands of gang members is a viable option to make the city safer … I don’t think so.”

Safer made a similar point to me when I asked him to respond to the idea that his efforts had backfired. “What is the argument?” he said. “Let’s leave these large powerful gangs intact?” He also noted that after the murder rate started dropping in 1994, it stayed more or less level for the rest of the decade, suggesting that the gang crackdown was not to blame for today’s chaos and violence.

There is undoubtedly an uncomfortable irony in the suggestion that dismantling the leadership of the Disciples and the other Chicago gangs was a mistake. Typically, we want our police officers and prosecutors to do the hard work of making cases against the people calling the shots, rather than racking up easy arrest numbers by hauling in kids who live and work at the bottom of the food chain. If we believe going after the bottom rungs and the top rungs is counterproductive, where does that leave us in terms of the solving today’s crisis?

It’s possible that the essential truth revealed by what happened in Chicago since the conviction of Larry Hoover in 1997 is that the problem of violence in the city’s poorest neighborhoods is not one that can be solved through policing. “It really shows that there’s a limit to what law enforcement can do,” said Papachristos. “We’re not going to arrest our way out of this problem. Sure, police should continue to make cases where gangs are involved in violence, where they’re really hampering community safety and well-being. … But that’s not gonna solve this.”

With the gang hierarchies largely wiped out, and the commercial motives for gangbanging significantly constrained, what we’re left with is a clear and sobering view of the reasons why so many young people in Chicago, and elsewhere, choose to participate in so stressful and dangerous a way of life. Those reasons have little to do with whatever benefits come from selling drugs.

“Look, I’ve never met a 13-year-old who said I’m gonna join a gang because 10 years from now I want to be the baddest drug dealer in my neighborhood,” said Eddie Bocanegra, executive director of the YMCA of Metro Chicago’s Youth Safety and Violence Prevention initiative. “They join for protection and status and reputation.” Bocanegra, who grew up as a member of the Latin Kings, continued: “Reputation is a form of capital. What other kind of capital do these young people have?”

That capital has perhaps never been so volatile a commodity. Desmond Patton, an assistant professor of social work at Columbia University who has studied the use of social media by gang members in Chicago, said that in an age when people’s reputations can be challenged casually and publicly online, “insults and language and comments have really come to shape retaliation in these communities.” Gang ties, meanwhile, make an insult to one person the basis of a conflict between many.

But there is a deeper, knottier issue that’s driving the bloodshed, said Lance Williams, and that’s the almost total lack of opportunity and resources for people growing up in impoverished neighborhoods. “We look at these conflicts as gang-related because these kids have ‘gang ties,’ ” Williams said. “But it really has nothing to do with a gang. When the only thing you have, the last thing you have, is your humanity, what you think of as your manhood, you get this skewed vision of what a man is. Because it’s the last front for you. You might as well be dead if you can’t hold onto that.” Regardless of what law enforcement officials try to do, Williams told me, the violence will continue until Chicago can give its young people something else.

For now, federal authorities appear to be pursuing a familiar strategy, taking aim at gang violence by going after some of its most menacing perpetrators. Their target at the moment: a gang called the Hobos, who fall somewhere between the ’90s-era Chicago gangs and the new, smaller cliques that predominate in the present. They’re older than most of today’s gangs—leader Gregory “Bowlegs” Chester is 39—and are accused of running an elaborate operation selling heroin, crack, and cocaine. But their alliance was forged from the wreckage of the ’90s crackdown; according to the Chicago Tribune, prosecutors allege that they represent “a new breed of gang … made up of members from diverse gangs who were once rivals.”

On Sept. 14, six alleged leaders of the gang Hobos went on trial for racketeering conspiracy and nine killings spanning seven years in what has been called the “biggest street-gang trial in recent Chicago history.” The Chicago Police Department recently estimated that the number of city residents with gang ties is close to 70,000.