This month, some of Slate’s legal eagles are proposing their favorite constitutional amendments, in the service of our effort, with Me the People author Kevin Bleyer, to rewrite the founding document. Here are proposals about the right to trial by jury, protecting informational privacy, amending the Constitution by national referendum, electing the attorney general, moving up the date of the presidential inauguration, restoring the balance of war powers, Supreme Court term limits, forcing Congress to fix the rules of congressional procedure, a right to health care, a right to vote, victims’ rights, campaign finance, elections, and the death penalty and solitary confinement.

Judicial Review (Article III)

Most of the Constitution’s checks and balances rely on majorities countered by supermajorities. The president can check Congress with the veto, and then Congress can override a veto with two-thirds of both houses. Congress can amend the Constitution, but only with two-thirds of both houses and the ratification of three-quarters of the states.

But one enormously important check is out of step with this balance: The Supreme Court can block the other two branches with a bare majority. The Supreme Court may vote 5-4 to strike down laws that were enacted by Congress and signed by the president (or enacted by a supermajority of Congress). Citizens United is one recent 5-4 example, and the pending decision on Obamacare may soon be another. Although the Constitution does not explicitly recognize the power of judicial review, many Founders contemplated it and presumed it would be part of the new government. It is time to recognize judicial review explicitly in our founding document, and at the same time, limit its use to reflect the Constitution’s overall balance of powers, with this amendment to Article III:

The courts may declare statutes void for being inconsistent with the Constitution. The U.S. Supreme Court may declare a federal statute void only if two thirds or more of the Justices concur.

My proposal is like Richard Ford’s in this Slate series about the 14th Amendment, with the addition that I’ve extended the supermajority voting rule to all federal statutes. My rule that would require more consensus on the court to restrict, for example, Congress’ power to regulate interstate commerce and campaign finance (which liberals would support) and also to give Congress more power over national security despite due-process objections (which conservatives would support). There’s one way in which I disagree with Ford—I don’t think that judicial review is “inherently anti-democratic.” As legal scholar John Hart Ely pointed out, sometimes the court needs to step in to protect democracy from itself: to stop majorities from entrenching themselves, from disenfranchising minorities, and from otherwise limiting political competition and debate. Moreover, the Constitution itself is fundamental law created by supermajorities of past generations. As I discuss in my recent book, The People’s Courts, in the mid-19th century, courts created the modern foundation for judicial review in pro-democratic terms: They were protecting the people’s constitutions against legislative folly, government corruption, and partisan abuses. Nevertheless, the courts shouldn’t exercise this power lightly, because it is such an exceptional intervention into the normal democratic process by such a small number of officials—and because it is so difficult to override the court by constitutional amendment.

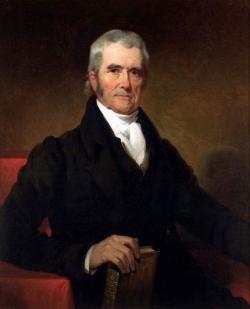

My supermajority voting rule would be consistent with the practice of judicial review for most of American history. For almost 200 years, from the Founding through the Burger Court, the Supreme Court struck down federal statutes by a one-vote majority only 24 times. Since then, the court has lost the instinct for restraint in this domain: The Rehnquist Court used 5-4 votes to strike down 20 federal laws in 19 years from 1986 to 2005, and the Roberts Court has done so three more times in the last five years. Chief Justice John Marshall’s Supreme Court was famous for its unanimity and for speaking with one voice. The controversial decisions by the Supreme Court striking down FDR’s New Deal legislation were 6-3 or unanimous. In 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren worked overtime to achieve a unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education in order to bolster the legitimacy of school desegregation. Even the Burger Court’s decision to legalize abortion in Roe v. Wade was 7-to-2. A supermajority voting rule might help restore a tradition of consensus on the Supreme Court, even if the rest of the government remains bitterly divided.

My supermajority idea isn’t new: In the 19th century and the early 20th century, congressmen proposed similar rules, particularly during the crisis over the New Deal during the Great Depression. The proposals faded away after 1937 in part because two justices, Charles Evan Hughes and Owen Roberts, changed sides and voted to uphold the New Deal after the Democrats’ landslide election in 1936—and before FDR announced his infamous court-packing plan. There are two crucial points from this episode. First, the Supreme Court follows the election returns—which means a supermajority voting rule would send a message the court might heed to exercise more judicial restraint generally. Second, voters supported the New Deal, but they did not embrace FDR’s court packing. Instead, they valued judicial independence, even if it was an obstacle to their policy preferences.

Unfortunately, the public’s support for judicial independence may be waning. The New York Times reported a poll last week showing the Supreme Court’s public approval falling to 44 percent, and showing that three-quarters of the public “say the justices’ decisions are sometimes influenced by their personal or political views.” A series of 5-4 decisions along partisan and ideological lines, including Bush v. Gore and Citizens United, has undermined the public’s trust that the court is making law, not playing politics. A supermajority rule would help reverse the trend by restoring an expectation of bipartisanship and a norm of consensus.

Many generations of American judges have built a court system that has commanded respect from the public, even when the public has sometimes disagreed with the substance of the courts’ rulings. Five justices—either on the left or on the right—can threaten that accumulation of legal and political capital. A supermajority rule might just save the court from itself.

We want your ideas for fixing the Constitution. Submit them here and vote on other great ideas.