Dahlia, your assessment of Chief Justice John Roberts’ ideological drift looks downright prophetic in light of Roberts’ opinion Friday in Lee v. United States. It may not be a blockbuster, but Lee brings vital clarity to a hazy and controversial area of the law: an immigrant’s constitutional right to a competent attorney.

The Sixth Amendment guarantees criminal defendants the right to “assistance of counsel,” which the Supreme Court has interpreted to include “effective” assistance of counsel. That doesn’t mean a defense attorney violates the Constitution any time she gives a questionable suggestion. Instead, the court has held that a lawyer’s advice crosses a constitutional line when it falls below an “objective standard of reasonableness” and there is a “reasonable probability” that the error “prejudiced” the defendant’s decision-making. When a defendant takes a guilty plea on his lawyer’s bad advice, he must prove that but for his lawyer’s mistake, “he would not have pleaded guilty and would have insisted on going to trial.”

Jae Lee, the defendant in the case decided on Friday, moved from South Korea to the United States at age 13. He has lived here for nearly three decades and runs a lawful business; his parents became citizens, but he remains a lawful permanent resident. In 2008, law enforcement officers discovered drugs, cash, and a gun in Lee’s house. A grand jury indicted him for possession of ecstasy with intent to distribute. Lee’s attorney strongly advised him to plead guilty since going to trial would be “very risky.” He repeatedly reassured Lee that he would not be deported as a result of his guilty plea. Lee took the deal. According to Lee, any time he raised the threat of deportation, his lawyer responded: “Why [are you] worrying about something that you don’t need to worry about?”

The lawyer was disastrously wrong: Lee’s conviction rendered him eligible for deportation, and the government planned to send him back to South Korea after he served out his sentence. Lee raised a Sixth Amendment claim, arguing that that his attorney’s advice was objectively unreasonable—and that if his attorney had given him accurate information, he wouldn’t have pleaded guilty. A district court rejected his claim, and an appeals court affirmed that decision.

In a 6–2 ruling, the Supreme Court reversed the lower court, ruling in favor of Lee. All parties agreed that the lawyer’s advice was unreasonable, so Roberts’ opinion focused on the second question: whether Lee would have elected to go to trial if his lawyer hadn’t given him mistaken advice. Roberts conceded that, if Lee had gone to trial, the outcome of his case would likely have been the same—prison time, then deportation. But Roberts noted that Lee’s primary fear was deportation, since he wanted to stay in the country to run his business and take care of his parents. Going to trial would probably have resulted in Lee’s deportation. But taking the guilty plea definitely led to deportation. So, Roberts concluded, Lee’s preference for trial was not “irrational,” and his attorney had prejudiced him by giving bad advice.

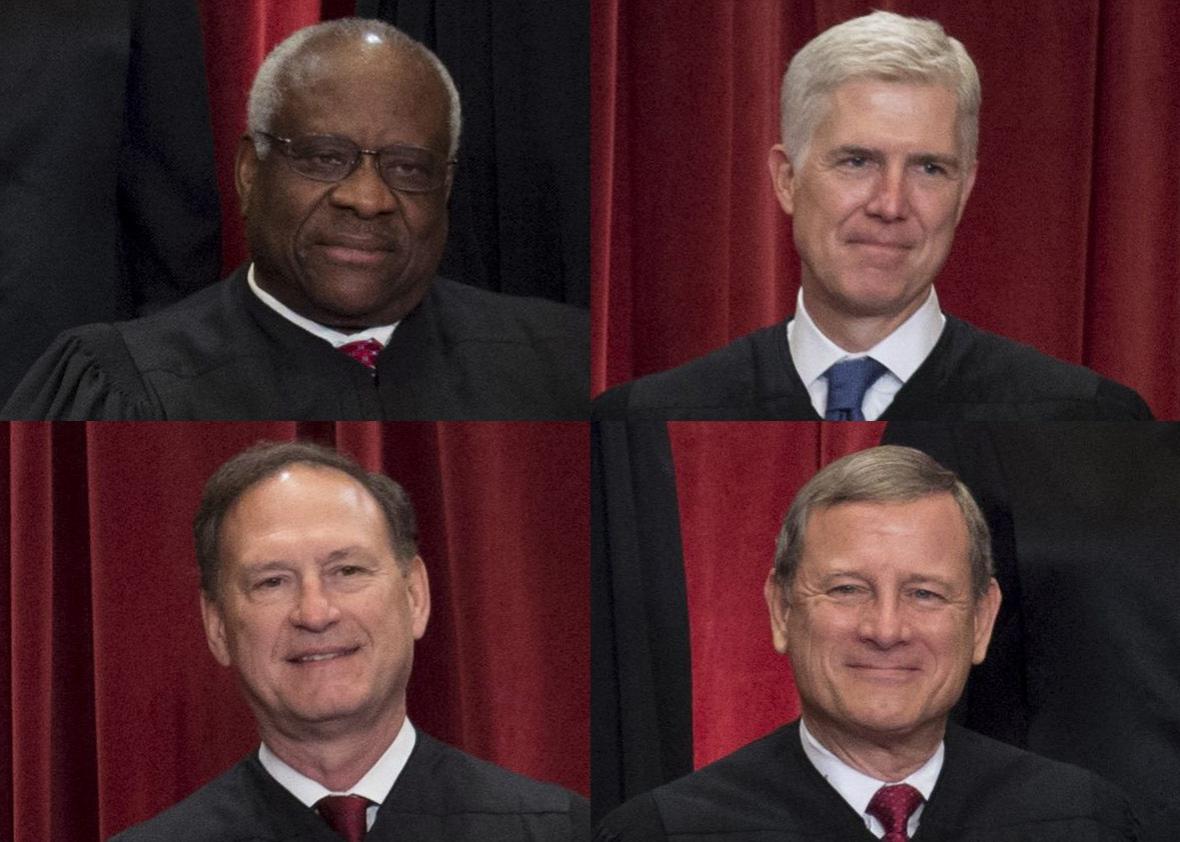

This common-sense outcome rankled Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito. Thomas, for his part, continued to reject the Supreme Court’s ruling that an attorney fails his Sixth Amendment duty when he does not inform a client that a guilty plea carries risk of deportation. Both Thomas and Alito also would’ve forced Lee to establish a reasonable probability that the result of a trial “would have been different than the result of the plea bargain.” Why? Thomas cherry-picks precedent to bolster his argument, but his dissent exudes disdain for any defendant who takes a guilty plea then raises an ineffective assistance of counsel claim. I suspect that in the Sixth Amendment context, both Thomas and Alito are more interested in creating an impossibly stringent standard than in effectuating true justice. The standard they promote is simply too demanding to serve any real purpose, other than slamming the courthouse doors on more defendants.

So Roberts’ opinion is a clear-cut victory for the Constitution, but it is also a reminder of how far right the court has drifted over the last few decades. When Roberts and Anthony Kennedy sit at the center of the court, something’s out of whack, and it isn’t hard to figure out what. Thomas and Alito’s hardline conservatism has shifted our perception of judicial ideology: Both justices are so far to the right that they make Roberts look like a centrist (which he isn’t) and Kennedy look like a liberal (which he can be, but usually isn’t). With Neil Gorsuch clearly joining the Thomas–Alito axis, the center of gravity on the court seems poised to slide even farther to the right.

Which means, I fear, that outside of conscience-searing cases like Lee’s, this court will not go out of its way to protect the little people from getting crushed by our merciless criminal justice system. I hope to be proved wrong.