Hello friends,

It was a busy morning at the court on Thursday, and yet a very aptly dramaless scene. Justice Anthony Kennedy read briefly from his majority opinion in the Texas affirmative action case, Fisher v. University of Texas, and Justice Samuel Alito then read from his lengthy dissent. The chief justice noted, almost as an aside at the end of the session, that both the tribal jurisdiction case Dollar General and the blockbuster immigration case U.S. v. Texas had split the court 4–4 and that the judgments of the courts below—which respectively reinforced tribal sovereignty in tort cases and blocked President Obama’s immigration action—were affirmed. Whiplash ensued.

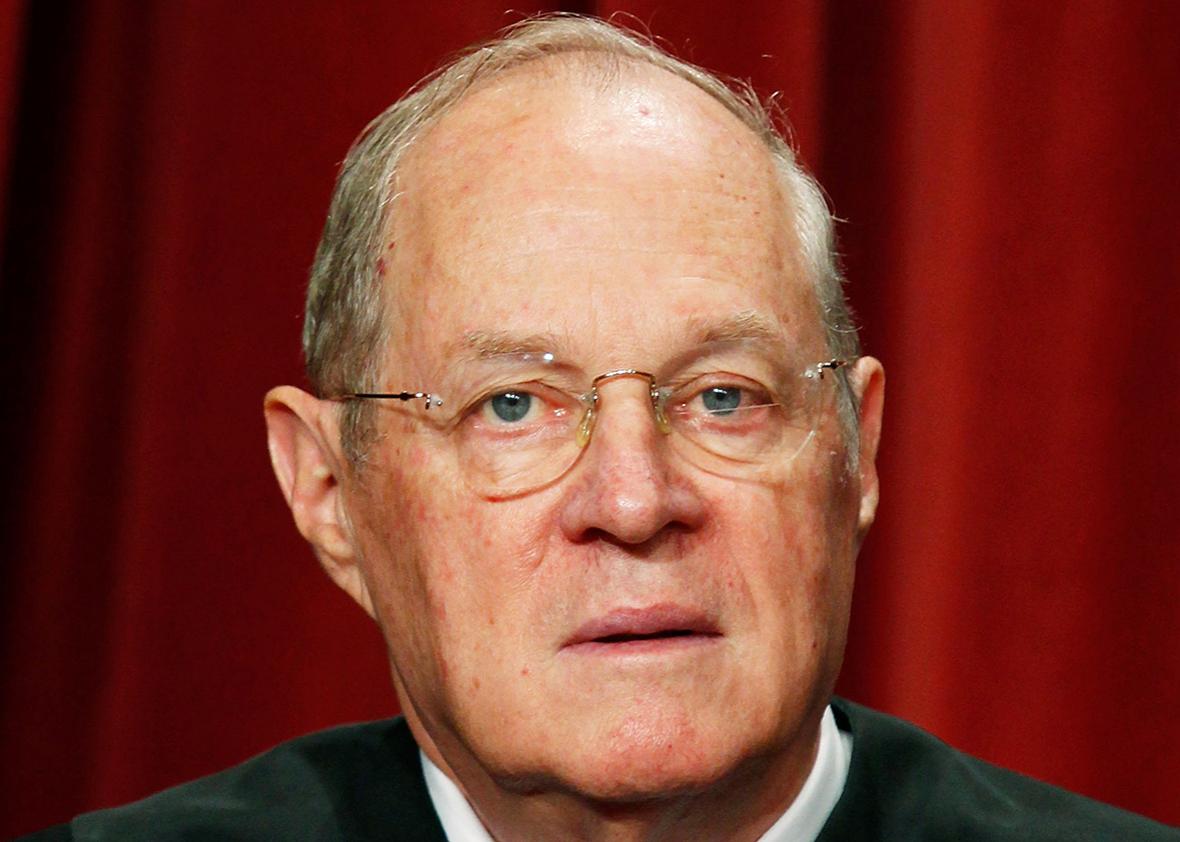

Reading the opinion in Fisher brings me back to the good old days, when it was Anthony Kennedy’s court and we all just whispered in it. I suspect more than one of you is already lighting small brush fires with the parts of his majority opinion that reference “dignity” and “continued reflection.” It’s very Hamlet-ish, yet workmanlike, and—in all—a rather strange effort from the same justice who has never previously signed off on any affirmative action programs.

So what is it that Kennedy has decided Thursday—is it as simple as saying that UT’s use of race as a “factor of a factor of a factor” in the university’s holistic review calculations is permissible because there is no good evidentiary record showing that the school’s Top Ten Percent Plan is creating a sufficiently diverse class? (So simple!) Certainly Kennedy rejects each of the four arguments made by Abigail Fisher and her lawyers but then doesn’t fully explain why it is he thinks the university has met its burden of showing that the admission program was narrowly tailored. And then he goes on to wax confusing about “intangible characteristics” and “diversity” and “dignity.” He insists, millennially, on a data-driven approach to diversity, as well as constant reflection, which is a bit like looking for a data-driven approach to sunbeams. All this rigor over mushiness drove Alito, in dissent, almost to madness. “These are laudable goals, but they are not concrete or precise, and they offer no limiting principle for the use of racial preferences,” he wrote. “For instance, how will a court ever be able to determine whether stereotypes have been adequately destroyed? Or whether cross-racial understanding has been adequately achieved?” (That’s one grumpy justice.)

So yes, a loss for Alito and Clarence Thomas and the chief justice on affirmative action, but mass confusion about what it all means in any concrete terms. Walter, last night you suggested that a 4–4 split on immigration would be the worst possible outcome and to be avoided at all costs. Instead the court did what we hoped it would not do and possibly made the composition of the court an election issue again. Maybe this answers Dawn’s question about whether we have in fact normalized a 4–4 court—or even whether a 4–4 court might be seen by some as a good thing for the next year. Or two. Or four …