Walter, Dawn, Dahlia, Dick, Akhil,

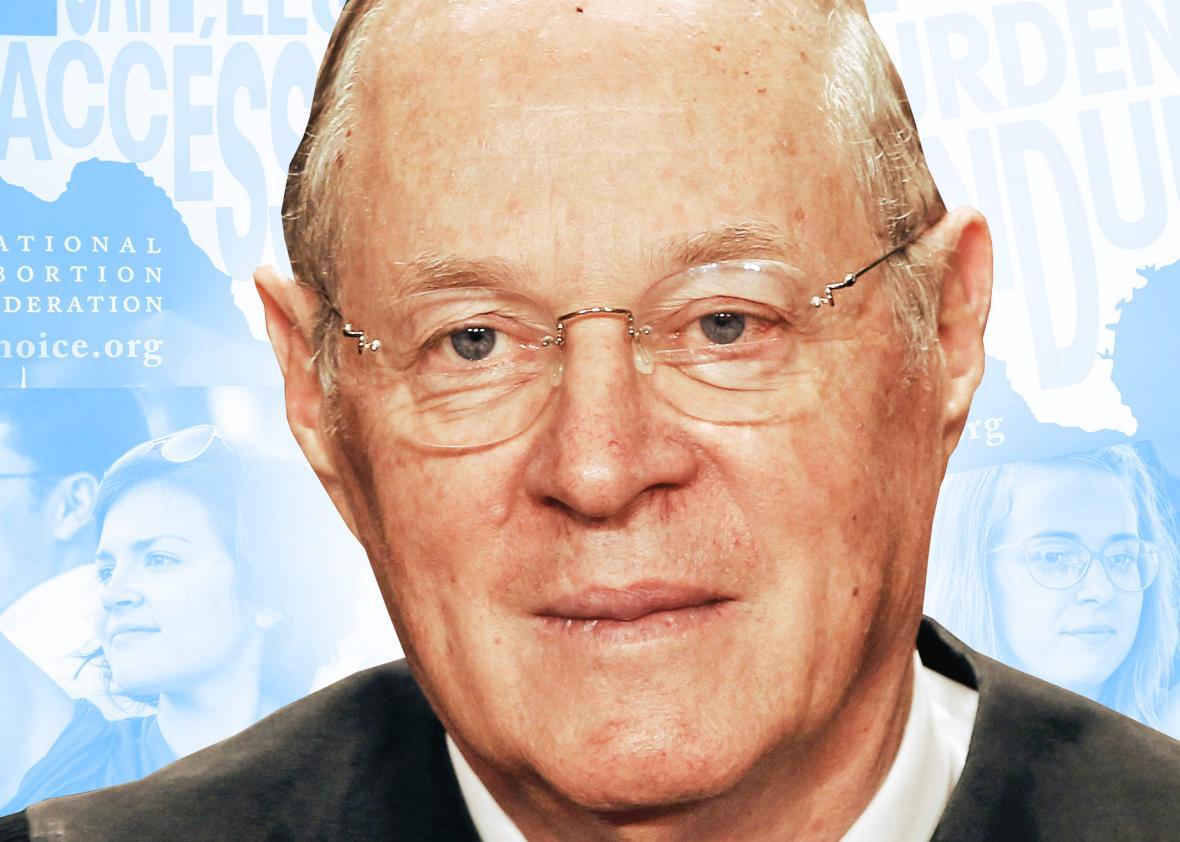

After the one-two punch of Fisher v. Texas and Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, it’s very clear that we’ve witnessed (yet another!) transformation of Justice Anthony Kennedy. Dahlia, you wrote that Kennedy’s Fisher opinion brought you “back to the good old days, when it was Anthony Kennedy’s court and we all just whispered in it.” But read together, Fisher and Hellerstedt suggest Kennedy’s jurisprudence has entered a bold new era, one less doctrinally rigid and more nuanced toward race and gender in the United States today.

Start with Hellerstedt, the most important abortion decision in nearly a decade. The last time abortion came before the high court, in 2007, it was in the form of a challenge to a federal ban on a type of late-term abortion misleadingly dubbed “partial birth abortion.” At the time, science clearly demonstrated that the banned procedure was actually safer than other forms of late-term abortions. But Congress outlawed it anyway, hypocritically suggesting women needed to be protected from receiving such a “disturbing” procedure.

Kennedy didn’t only buy it—he wrote the majority opinion upholding the federal law. His decision in the case, called Gonzalez v. Carhart, included an incredibly offensive, paternalistic paragraph citing unsubstantiated claims from anti-abortion amicus briefs to illustrate why women must be protected from their own decision to receive an abortion:

Respect for human life finds an ultimate expression in the bond of love the mother has for her child. The Act recognizes this reality as well. Whether to have an abortion requires a difficult and painful moral decision. While we find no reliable data to measure the phenomenon, it seems unexceptionable to conclude some women come to regret their choice to abort the infant life they once created and sustained. Severe depression and loss of esteem can follow.

Fast forward to 2016 and Hellerstedt. Texas’ arguments in support of its draconian abortion regulations were fairly similar to Congress’ justifications for its late-term abortion ban, centering around the need to “protect women.” But this time, Kennedy didn’t buy it: He assigned the majority opinion to Justice Stephen Breyer, who squarely rejected specious junk-science arguments in favor of a careful review of empirical evidence about the safety of abortion and the gratuitousness of Texas’ TRAP law. No more hysterical women in need of protection from their irrational, immoral decisions; no more sexist paeans to stereotypical motherhood. Instead, Breyer’s opinion rested on data, science, and a respect for women’s own decision-making abilities. Hellerstedt viewed women as rational actors; Carhart viewed them as impulsive walking wombs, craving babies whether they knew it or not.

We see a similar evolution in Kennedy’s affirmative action jurisprudence. Kennedy dissented in 2003’s Grutter v. Bollinger, in which the court upheld the University of Michigan Law School’s affirmative action program. The Michigan law, the majority explained, engaged in a “highly individualized, holistic review of each applicant’s file” using race as just one of many factors in the admissions process. Yet that wasn’t enough for Kennedy, who insisted this use of race was still too “outcome determinative” and that the majority had deferred excessively to the school’s promise that “its admissions process meets with constitutional requirements.”

What a difference 13 years makes! Kennedy’s Grutter dissent might as well be a critique of his Fisher majority. In Fisher, Kennedy acknowledged that the University of Texas actually uses two race-conscious programs in its admissions process—then largely deferred to the university’s claim that its use of affirmative action passes constitutional muster. Thirteen years ago, Kennedy huffed that the court should have reviewed Michigan Law’s program more rigorously and warned darkly of racial quotas. Now Kennedy asserts “considerable deference is owed to a university in defining those intangible characteristics, like student body diversity, that are central to its identity and educational mission.”

Why did Kennedy change his tune so dramatically? One possibility is the justice has woken up to the fact that the court cannot promote constitutional equality by ignoring the reality of sexism and racism. On the topic of race, especially, Kennedy must see the feeble implausibility of Chief Justice John Roberts’ argument that “the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” In fact, Kennedy seems to have drifted into the liberal-pragmatist camp on issues of discrimination, seemingly recognizing the wisdom of Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s rejoinder to Roberts’ maxim: “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to speak openly and candidly on the subject of race, and to apply the Constitution with eyes open to the unfortunate effects of centuries of racial discrimination.” Did Kennedy simply start reading a newspaper? Was he swayed by Sotomayor’s advocacy behind the scenes?

Even if Sotomayor played no role in Kennedy’s reversal on affirmative action, I have to believe Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg helped him to see the light on abortion. Ginsburg’s dissent in Carhart threw Kennedy’s opinion out a sixth-story window, drove over it with an SUV, pried it off the road, and set it on fire. She noted, citing extensive evidence, that the vast majority of women do not regret their abortions and lambasted Kennedy for citing women’s “fragile emotional state” to justify depriving them of “the right to make an autonomous choice.”

She reminded Kennedy that “eliminating or reducing women’s reproductive choices is manifestly not a means of protecting them.” And she pilloried her colleagues on the right for returning the court to the days when justices blithely asserted that “[m]an is, or should be, woman’s protector and defender. The natural and proper timidity and delicacy which belongs to the female sex evidently unfits it for many of the occupations of civil life. … The paramount destiny and mission of woman are to fulfil[l] the noble and benign offices of wife and mother.” Would Kennedy really have dared to risk Ginsburg’s ire, once again, to save a law that is even more transparently pseudoscientific and paternalistic?

Finally, I have to believe that Obergefell v. Hodges changed Kennedy in some fundamental way. Kennedy’s majority decision affirming the constitutional imperative of marriage equality also functioned as a broad guarantee of “equal dignity” to all within the Constitution’s reach. Perhaps, in creating new doctrine upholding the equal dignity of gays and lesbians, Kennedy came to realize his old doctrines about race and gender are impractical and insufficient. Applying rigid rules about absolute colorblindness and stereotypical ideas of motherhood—to the detriment of minority students and women—doesn’t seem to recognize anybody’s dignity. Maybe Kennedy has finally taken to heart the very Posnerian lesson that realism and flexibility trump doctrinaire formalism in the realm of constitutional jurisprudence.