Thursday’s blockbuster opinion in the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. Inclusive Communities Project case will be primarily and justly remembered for interpreting the Fair Housing Act to include a disparate-impact cause of action. In anti-discrimination law, “disparate treatment” requires an intent to discriminate, while “disparate impact” can allow a plaintiff to win even in the absence of discriminatory intent. For instance, if an entity has a policy that disproportionately affects a protected group, it has to justify that disparity even in the absence of any allegation of discriminatory intent. If it cannot produce such a justification, it will lose. As many progressives have already noted, this interpretation of the FHA is a big win, as discriminatory intent is often difficult to prove.

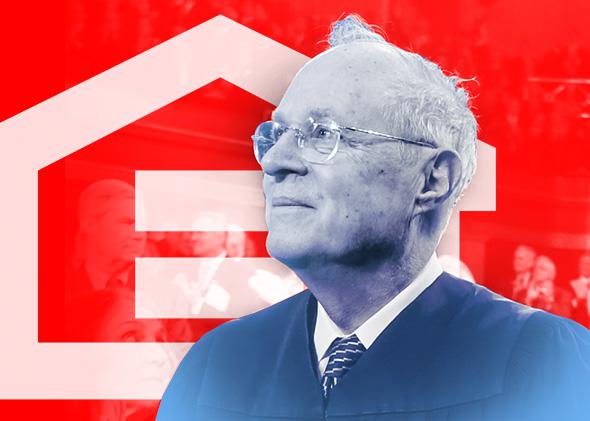

While less obvious, however, there is a passage in the FHA case that can also be counted as a potential win for progressives. On Page 17 of the slip opinion, Justice Anthony Kennedy writes, “Recognition of disparate-impact liability under the FHA also plays a role in uncovering discriminatory intent: It permits plaintiffs to counteract the unconscious prejudices and disguised animus that escape easy classification as disparate treatment.” (Emphasis mine.) Disparate impact has long been seen as a way of proving “disguised animus”—so that is nothing new. However, the idea that disparate impact can be used to get at “unconscious prejudices” is, to my knowledge, an idea new to a Supreme Court majority opinion.

The idea of “unconscious prejudice” is that one can have prejudices of which one is unaware that nonetheless drive one’s actions. It has been kicking around in academia for years. As Mahzarin Banaji and Anthony Greenwald discuss in Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People, Greenwald created the test to assess such unconscious biases in 1994. This test can now be found at implicit.harvard.edu. Since taking academia by storm, it has migrated over to industry—companies ranging from Google to Pfizer have laudably adopted it to assist in making their workplaces more inclusive.

Kennedy may have been thinking of this vision of prejudice back in 2001, when he concurred in a case involving individuals with disabilities: “Prejudice, we are beginning to understand, rises not from malice or hostile animus alone. It may result as well from insensitivity caused by simple want of careful, rational reflection or from some instinctive mechanism to guard against people who appear to be different in some respects from ourselves.” Put differently, discriminatory intent does not mean you have to be a torch-wielding villager. It can be a reflexive response to difference.

Until today, however, I know of no majority opinion that described disparate-impact liability as an attempt to address the negative effects of unconscious prejudice. This is important because it reframes the jurisprudential debate about why we have disparate-impact causes of action under Title VII (which prohibits employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, and sex) or the ADEA (which prohibits discrimination on the basis of age). It recognizes that disparate-impact liability might be useful in those cases because unconscious biases might be keeping minorities and women back even in the absence of conscious discriminatory intent.

Moreover, while Kennedy’s majority opinion states that such unconscious prejudices escape “easy classification” as disparate treatment, it does not say that they could never qualify as such. To the contrary, Kennedy puts smoking out unconscious prejudices under the heading of “uncovering discriminatory intent.” This is particularly important because disparate impact is not cognizable under the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause. Since 1976 the Supreme Court has said that discriminatory intent is required. However, as Justice Samuel Alito pointed out in Thursday’s case, disparate impact can be used as evidence of discriminatory intent, even in constitutional cases. So to the extent that unconscious bias counts as discriminatory intent, the kinds of cases cognizable under the Equal Protection Clause may expand as well.