Marty, I think your observation about the extent to which the King decision is a kind of referendum on Justice Antonin Scalia’s brand of textualism is incredibly insightful. I also find myself wondering if any of you were struck by the tone of the Scalia dissent; it’s getting a lot of attention for the whole “argle bargle 2.0” verbiage (Applesauce! Jiggery Pokery! SCOTUScare!) but is there something else worth saying about it?

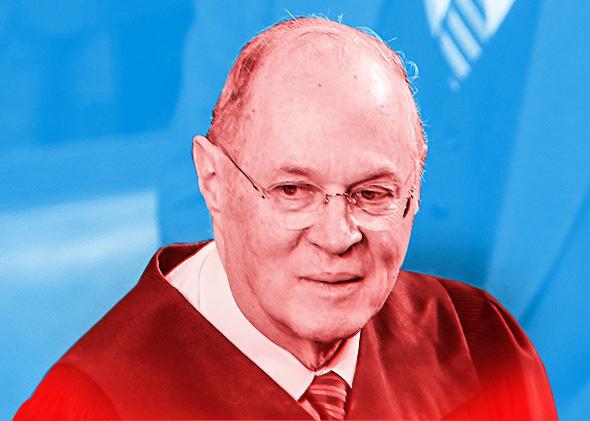

Marty, I also want to circle back to something you flagged at the very end of your post—about what might have animated Justice Anthony Kennedy—who was not a fan of the Affordable Care Act back in 2012, to switch positions this time. Marty suggests that:

As in many high-profile cases, there’s been a great deal of speculation about what the chief justice and Justice Kennedy might decide in King—and, more particularly, what their motivations would be. Perhaps we ought to take them at their word: “In a democracy, the power to make the law rests with those chosen by the people. … [I]n every case we must respect the role of the Legislature, and take care not to undo what it has done.”

Is that what changed? Is the same strange schism that exists between the nihilist (“break government”) and pragmatic (“meh, government”) elements of the Republican Party playing out here between Scalia and Kennedy? At some level at least, Kennedy was consistent across Sebelius and King in that he seemingly believed government intended the exchanges to work.

The other question I have for you all is whether, as Mark reports, Kennedy is staking out any new ground in the Texas Fair Housing Act case. This was an incredibly worrisome case for civil rights and fair housing groups—one that terrified the Obama administration. And here is Kennedy reading the Fair Housing Act to have a cognizable disparate impact claim. In the face of a very deliberately “color-blind” conservative bloc at the high court, Kennedy tends to walk his own path on race cases, staking out a kind of conservative middle ground that is consistent with his jurisprudence in the 2007 school busing case, Parents Involved. Unlike Chief Justice John Roberts who wrote at the time that, “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race,” Kennedy concurred separately to write that when it comes to ensuring freedom for all, “our highest aspirations are yet unfulfilled.” He splits off from the conservative majority because, as he puts it, “The enduring hope is that race should not matter; the reality is that too often it does.”

Kennedy objected in the Parents case to a school integration program that “threaten[s] to reduce children to racial chits valued and traded according to one school’s supply and another’s demand.” He declined to sign off on Justice Stephen Breyer’s dissent. He staked out a middle posture but agreed that race discrimination should be remedied, just not in ways that smacked of “widespread governmental allocation of benefits and burdens on the basis of racial classifications.”

To be sure, Kennedy can get himself tangled up in what he defines as constitutional remedies and “constitutional concerns,” but the Texas Fair Housing Act case reaffirms that at least he understands—in some contexts at least—that we are not so much post-racial as exhausted. I have heard from some quarters that the liberal justices sacrificed far too much to sign onto this middle way of Kennedy’s. So curious to know your thoughts.

Dahlia

Read the previous entry, by Kenji Yoshino. Read the next entry by Richard Posner.