There are three truly striking things about the cellphone decision this morning.

First, it is a dramatic example of how the application of constitutional rules has to change with social change. The prior constitutional law permitting—without a warrant—searches incident to arrest of the items arrestees had on their person was broad and clear. But every justice saw that cellphones were fundamentally different from all the “stuff” police could shake out of suspects’ pockets and inspect. Conceptions of what constitutes a reasonable search, like conceptions of what constitutes equality, do change.

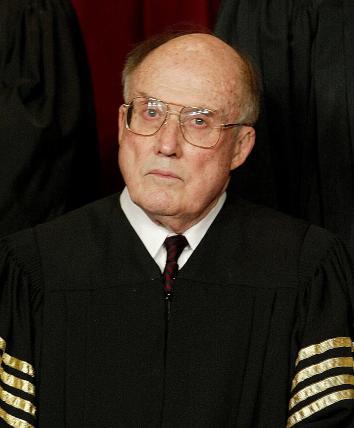

Secondly, the court has moved to more robust substantive protections of Fourth Amendment privacy rights just as it has cut back on the remedies available for violations of those constitutional norms. Georgetown Law professor Marty Lederman pointed this out to me this morning as the positive side of Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist’s successful campaign to limit the exclusionary rule and damage suits against law enforcement officers. The court now may feel freer to announce substantive protections when criminal convictions are not so clearly at risk and officers are protected from suit. (Officers, for example, are no longer liable for conduct undertaken before the court has opined on a point.) This stealth Rehnquist remedial revolution—as both Marty and his Georgetown colleague Irv Gornstein have discussed informally for years—may have actually allowed the court to be more aggressive about issuing substantive pronouncements that will check the government.

Thirdly, the court may no longer be the head cheerleader for the war on drugs. The Supreme Court decisions from the 1970s that gave the green light to oppressive police investigative practices were to a large degree driven by the perceived need to suppress the supply of drugs. Consider for example United States v. Robinson (1973), which allowed law enforcement officers to search without a warrant a crumpled cigarette package (that turned out to have drugs). Decided at the height of the national drug frenzy, cases like Robinson were the handmaiden of mass arrests. Because it would have been too costly and complicated to obtain warrants every time the police did of a sweep of low level street dealers, intrusive searches without warrants were a key part of drug control efforts that rely on mass arrests.

In today’s Riley decision, the court notes, almost as an aside: “We cannot deny that our decision today will have an impact on the ability of law enforcement to combat crime”—a fact that does not seem all that troubling to the justices, at least not as troubling as it would have been in prior decades.

To my mind, the mass incarceration that resulted from the misguided war on drugs has been the great unappreciated civil rights issue of our time. The court, like much of the country, may finally be war-weary and may have come to the realization that the cost in human suffering, civil liberties, and community disruption has been far too great to justify any positive results.