The question for today is how well the Supreme Court is grappling with new technology. In Riley v. California, the court decided that the police cannot read through the cellphone taken from someone they arrest without first obtaining a warrant. In ABC v. Aereo, the court ruled that a newfangled system for transmitting television programs over the Internet violated the copyrights of the broadcasters who own those programs.

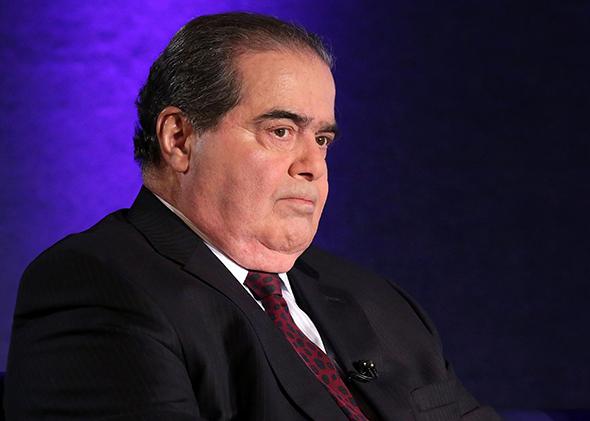

Last year, Justice Antonin Scalia famously wrote a separate opinion in a case involving the patentability of a genetic test in which he said of the majority’s discussion of the “fine details of molecular biology” that “I am unable to affirm those details on my own knowledge or even my own belief.” Scalia did not explain how he could agree with the majority’s holding without understanding the facts of the case, and one got the distinct impression that he did not think the majority understood the facts of the case either. A molecular biologist I know concurs.

Fortunately, Riley involves a piece of technology that we all understand. Riley, the defendant, possessed a smartphone, which the court helpfully defines as “a cell phone with a broad range of other functions based on advanced computing capability, large storage capacity, and Internet connectivity.” Another defendant in the case owned a flip phone (“a kind of phone that is flipped open for use and that generally has a smaller range of features than a smart phone”).

Various earlier opinions established that when the police arrest someone, they are allowed to search his person for dangerous items and contraband. They can flip through his wallet. They can look at personal photos he may be carrying. They can even read his diary if he happens to have it in his pocket. Prosecutors can then use this information, if it is incriminating, to convict him of crimes. So if they can do all these things, shouldn’t they also be able to flip through his phone, and then use the information they find there—addresses, incriminating photos, messages—to convict him of crimes?

The opinion, written by Chief Justice John Roberts, points out that modern cellphones are truly different from old-style pocket clutter. They contain gigabytes of personal data—names and addresses of associates, personal messages, medical information, sexts and naked selfies (he actually doesn’t mention the last two). My cellphone contains the exact route, speed, and even elevation of occasional jogs along Lake Michigan; it even contains the number of steps I take in a given day. And it will tell anyone who looks at it how bad I am at chess, which I would like to keep to myself above all.

So it is gratifying that a court that often has trouble understanding new technology had little trouble holding that the cellphone represents something new—something that justices addressing searches incident to arrest in opinions written 30 or 40 years ago did not anticipate, to say nothing of the founders. Because people’s privacy interests in the contents of their cellphones are so strong, police cannot examine them without first getting warrants.

All that said, I sympathize a bit with Alito, who in a separate opinion wonders why the Supreme Court should decide how important the privacy interest is in one’s cellphone contents. Isn’t this a better question for legislatures? The court applies a balancing test in Fourth Amendment cases, under which the police can search a person without obtaining a warrant if the degree to which the search intrudes upon privacy is less than the degree to which the search is needed for a legitimate government interest—typically, in catching criminals and protecting police from danger.

How exactly does this court know how significant the privacy interest is? Many people don’t care much about their privacy; others do. Maybe those who care a lot don’t put personal information on their cellphones, or they ensure that it is encrypted or otherwise protected. Or they put information on their cellphones that you or I might consider personal but they don’t. Indeed, technology is not the only thing in flux here; so are social norms and personal beliefs about what information it is appropriate to share and what information should be kept to oneself.

And if the justices know what a smartphone is, they don’t know what these norms and beliefs are, and certainly not for the great mass of the population younger than they are, who have grown up with smartphones, Facebook, personal blogs, the Web. The court doesn’t seriously try to figure out how much people are really injured if a police officer looks at information on their cellphones. To do so, one would need to engage in a massive amount of empirical investigation, using surveys, focus groups, and market research—the stuff of committee hearings before legislatures. One senses, as is so often the case, that the justices are relying on their own personal experiences. They are thinking about what’s on their cellphones and how they would feel if a police officer saw them. As for the rest of society, we’re as opaque to them as DNA.