Was the court’s decision in the case about a no-protest zone at a Massachusetts abortion clinic an appropriate compromise? The answer depends on what one makes of the practice of “sidewalk counseling,” which is now more available to protesters who may congregate in front of clinic entrances. Make no mistake about the fact that these activities place a real burden on women seeking not just abortions but the whole range of contraceptive and reproductive health services, cancer screenings, and the like. The court notes that actual physical obstruction is already prohibited and can be further regulated by other laws. True enough, but that blinks the serious psychological intimation that remains when a person is surrounded by a group set on changing her ways as she is attempting to make her way through the crowd surrounding the entrance to a clinic.

This case is really about the unwilling listener who is forced to submit to lectures she does not want to hear at a time of stress. (It would be easy enough to a protester standing a mere 12 yards away to hold up a sign saying, “Talk to me about your choice.”) Like many of the court’s decisions, this one draws a line across society on social and economic grounds. The wealthy elite—like Supreme Court justices—rarely if ever have to make their way through crowds that surround them and berate them or even plead with them in softer voices. Those who work at the Supreme Court (or at law firms like mine) most often drive (or are driven) into underground garages at work or at doctors’ offices. It is students, secretaries, school teachers, and other ordinary people who have to get off the bus or the subway and push their way through hostile crowds of those who may get in their faces and do everything they can to impede their entrance into a clinic. The gauntlet of the final entrance is but the final step that follows from the relentless creation of hurdles that are effectively depriving the most vulnerable women of the right that was promised to them in Roe v. Wade.

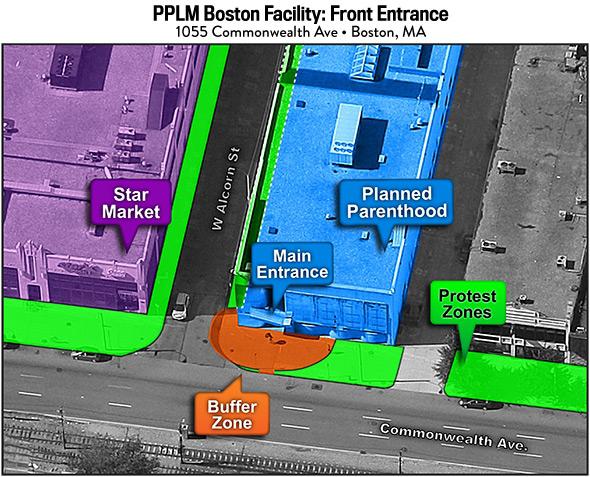

As for the burden on freedom of speech, I’m inclined to agree with Dick’s argument over Larry’s well-argued piece in the New York Times and his Breakfast Table post. As Dick notes, the heart of the First Amendment is “the marketplace of ideas and opinions.” The creation of a relatively small space free of protesters in front of a clinic hardly shuts off debate. In defense of the notion that the space is relatively small, I post here one of the maps in the brief for Planned Parenthood of Massachusetts and Planned Parenthood Federation of America (a brief on which I was co-counsel.) The blue shows the clinic, the orange shows the buffer zone, and the green shows all the space that is available for speech very nearby.

Map data courtesy of Google

Why did Justices Breyer, Ginsburg, Sotomayor and Kagan join the chief justice’s ruling to strike down the state law providing for the buffer zone? Well, Roberts did go out of his way to leave other possibilities for clinic protection available to legislatures. His approach is greatly to be preferred to Justice Scalia’s. In a remarkable statement, Scalia suggests that Roberts made a deal with the liberal justices, saying, “I prefer not to take part in the assembling of an apparent but specious unanimity.” This raises issues of such import about the proper role of judging that I will address them—or at least scratch the surface—in a separate post.