I agree that the Supreme Court’s opinions tend to be too long. The padding often muffles the meaning, and I also think it’s one reason journalists sometimes screw up in the instant of first reporting a major decision (as some infamously did when the Obamacare ruling came down last year, and after Bush v. Gore). Another reason the opinions lend themselves to error on a quick read: They don’t have clear headlines. Would it really kill the court to say at the top of the very first page: Hey, there are two parts to this ruling. The first part was decided 5–4. Here’s the breakdown of justices, and here’s what the majority said. The second part was 7–2, and ditto. On the other hand, maybe I’m arguing against my own interest here, since the current, more confusing, setup helps me justify my three years of law school. (Watch me blow it next week!)

Walter, you took us back to the 1996 passage of the Defense of Marriage Act, saying that at the time, no one thought it was conceivable that the Supreme Court would declare it unconstitutional. Maybe, but a few well-placed and prescient people argued from the start that the court should do so. In the summer of 1996, two months DOMA before was enacted, then-Gov. William Weld of Massachusetts (a Republican) said he thought the law would fall because “I am a proponent of the U.S. Constitution, which guarantees full faith and credit to a judicial or juridical act of another state.” A couple of members of Congress cited DOMA’s unconstitutionality in refusing to vote for it. Here’s the beginning of a Boston Globe article from September 1996: “The bill passed by Congress limiting the recognition of same-sex marriages is sure to be signed into law by President Clinton, but whether it survives challenges in the courts is an open question, legal scholars say. ‘There’s no doubt at all the constitutionality will be in question,’ said Laurence H. Tribe, professor of constitutional law at Harvard Law School.” And here is Larry Kramer, future dean of Stanford law school, in the Yale Law Journal in May 1997: “DOMA is unconstitutional.”

During argument in one of the gay-marriage cases, Justice Antonin Scalia pressed Ted Olson, one of the lawyers challenging California’s same-sex marriage ban, on “when did it become unconstitutional to exclude homosexual couples from marriage?” Olson asked back, “When did it become unconstitutional to prohibit interracial marriages?” and then said, “There’s no specific date in time. This is an evolutionary cycle.” Scalia’s point, of course, is that the men who wrote the Constitution had no earthly intention of recognizing a right to an institution they wouldn’t have imagined. Since most of the justices aren’t originalists, I don’t think that’s a winning argument, though I’m expecting to hear it loud and clear from Scalia in dissent. I’m interested, though, that when the Volokh Conspiracy polled its readers on Scalia’s timing question, 24 percent said the Constitution “began to require states to recognize same-sex marriage before or during the 1700s”—during the founding era—and 29 percent dated the beginning to the 1800s, which tracks to the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection under the law in 1868. Added together, that’s more than half of the readers who responded.

Since I’m not an originalist, I don’t care much how many generations of constitutional understanding a ruling in favor of gay marriage would reflect. And if Scalia thought recognition of gay marriage would solve a deep social problem, he wouldn’t either: He calls himself a “faint-hearted originalist” because he believes that the court’s 1954 decision to desegregate public schools was correct even though that one, too, would have raised eyebrows among the Founders.

I bet some of the Founders would take it all in and raise a pewter of ale to a nice gay or lesbian couple. But to me, what matters much more is the social moment you point to, Walter. Scales have fallen—are falling—from our collective eyes. When it becomes clear that something was unthinkable merely because most of us hadn’t really thought about it, the public can just shift perspective and accept it. That explains the burgeoning support for gay marriage in the polls. And I think it will sway a majority of the justices as well. I love writing about same-sex marriage because it is moving, in both senses of the word.

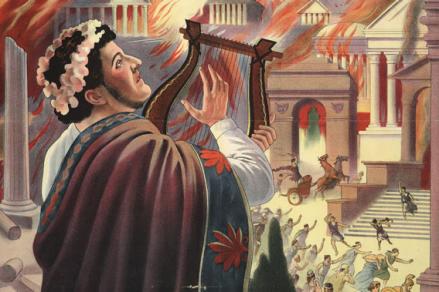

And if you like long pedigrees, here’s this tidbit: Nero married a man in a public ceremony and accorded him the honors of an empress. And same-sex unions continued in Rome for more than 300 years. Score one for the empire.