This is quite a news day. I can hardly imagine the spike in traffic on Slate as readers work their way through the latest developments. As others are charged with parsing the season finale of Mad Men, let me provide some brief reactions to Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, the decision on affirmative action handed down by the Supreme Court earlier today.

As Emily mentions, the case is notable for ducking all the interesting questions. Commentators expected the court either to reject or endorse affirmative action by state universities, but instead the majority opinion, written by Anthony Kennedy, merely scolded the lower court for failing to follow an earlier Supreme Court decision, which applied “strict scrutiny” to all programs with explicit racial classifications. That means that affirmative action using an explicit racial classification is permissible as long as the government can show that it advances a compelling government interest. Kennedy sent the case back to the lower court, where the University of Texas must now show that its affirmative action program—which gives some real but ambiguous weight to the race of the applicant—advances the university’s legitimate educational goals.

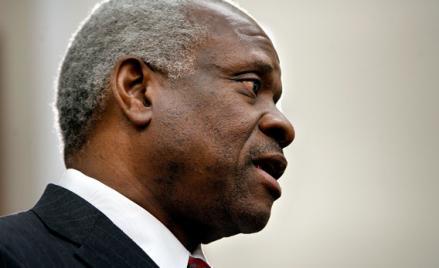

The real action can be found in a concurring opinion by Justice Clarence Thomas and a dissent by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Thomas rather powerfully shows how the court has boxed itself in. The court says that an overt racial classification in a law must be “narrowly tailored” to advance a compelling government interest. The strict-scrutiny standard is very high (“strict in theory, but fatal in fact,” as many wags have put it). In a case from the 1950s, Thomas points out, the court found that racial segregation could not be justified even if it could be shown that if segregated schools were banned, white communities would strip funding from public schools and send their children to private schools, thus hurting black children more than a segregated system would. If the survival of an educational system cannot be a “compelling interest” that justifies racial classifications, then its mere putative improvement through diversification of the student body cannot be, either.

Part of what is going on here is the diversity rationale was always phony, or least partially phony. I have spent my adult life in universities, and it seems pretty clear to me that the real motivation for affirmative action is a lot more complex than the idea that diversity improves educational outcomes, though it might. Affirmative action is based on all kinds of factors—a desire to make up for past injustices, a feeling that African-Americans should receive some advantages to counteract racism that they continue to face, a desire to propel more African-Americans into high-status positions where they can exert long-overdue influence on the direction of society, the thought that black students should have role models (for faculty hiring), and then simple liberal guilt, fear of being seen as racist, and pressure from constituencies. The Supreme Court has ruled out many of these rationales while (so far) recognizing that diversity alone can be a valid rationale, and so to a large extent universities are just pretending when they cobble together a diversity rationale for affirmative action policies based largely on other motivations. That is why social scientific evidence that affirmative action advances educational outcomes by enhancing diversity is so weak. That was never its reason for existence. And if the evidence isn’t there, eventually affirmative action programs will be struck down: that’s what strict scrutiny will demand.

So the days of explicit racial classifications may be numbered (barring a change in the ideological composition of the court). But those who oppose affirmative action because of its conflict with meritocracy have less cause for celebration than they may think. The lawyers for Abigail Fisher, the white applicant to UT Austin who brought today’s case, did not challenge an important element of the University of Texas’ admissions system, which is that the university will accept the top 10 percent of the class of each high school in Texas. This rule sounds race-neutral, but as Ginsburg notes in her dissent, it was just a disguised form of affirmative action, based on the background fact that Texas schools are highly segregated. The top 10 percent of an all-black school in a poor school district will be more poorly qualified for higher education than the 10–20 percent tier of an all-white school in a wealthy district, yet it’s the first group that automatically gets to go the University of Texas. This is a crude way to engage in affirmative action, and if the court bans explicit racial classifications while permitting this kind of disguise, which universities will rush to embrace, then it’s hard to see how the law will advance the meritocratic ideal embraced by opponents of affirmative action.