For the past 20 years, American politics has been defined by Republican revolt. The right-wing radicalism that now worries the whole world first emerged in response to Bill Clinton’s election in 1992. It’s not that Republicans were never extreme before that time. Challenges to the legitimacy of federal authority from the people who now identify as Republicans trace back to pro-slavery attempts at nullification and segregationist assertions of states’ rights. But it was 20 years ago that the Congressional wing of the GOP, led by House Speaker Newt Gingrich, adopted belligerent noncooperation as its defining stance.

It was Gingrich who turned bipartisanship from Washington’s greatest virtue to its most reviled vice. Under his leadership, congressional Republicans refused any quarter on Clinton health care reform and supplied no votes for the economic plan that spurred the long boom of the 1990s. In their new mode, Republicans refused to vote on presidential nominations and buried the White House in investigations and subpoenas. It was Gingrich who in 1995 invented the tactic of refusing to raise the debt ceiling as a cudgel to get Clinton to agree to outsize spending cuts. It was Gingrich who invented the tactic of shutting down the government for the same end.

Bill Clinton’s view was that the Republican refusal to be reasonable was all about him. Because he was elected in a three-way race without an absolute majority, he thought Republicans never accepted him as legitimate. An alternate view is that the radical Republican style was largely a matter of incentives and rewards. Abandoning traditions of responsibility and civility won the GOP control of both houses of Congress in 1994. Rejecting any compromise brought Republicans the perks and power of majority control for the first time in 40 years. Thus did the politics of total resistance become their path of least resistance.

In subsequent years, the conservative movement built up an elaborate incentive structure to favor extremist views and tactics by individual politicians. State Republican parties redrew maps to create safe congressional districts where appealing to swing voters would no longer be required. Organizations like the Club for Growth and Americans for Tax Reform targeted Republican moderates for political extermination, recruiting primary challengers to run against them, scripting their attack ads and funding their campaigns. The Tea Party emerged partly out of inchoate anger at social and economic change, and partly in response to these incentives.

In his first term, Barack Obama did his part to encourage the GOP hostage taking. When Republicans again demanded lopsided budget cuts in exchange for a debt ceiling increase in 2011, the president was too willing to negotiate, giving them a victory in the form of the budget sequestration that took effect this year. By the time of his re-election campaign, however, Obama had learned the lesson that compromising with bullies only fuels their aggression. This time, he refused to negotiate, sending a clear message that the debt ceiling could not be used for leverage.

Wednesday’s unconditional surrender by House Speaker John Boehner was a watershed because it points to a change in the incentives that have favored two decades of reckless Republican behavior. The party’s Senate elders are chagrined and embarrassed. Boehner’s unwillingness to stand up to the Tea Party has made them look ridiculous. It has driven a wedge between the GOP and Wall Street, which was appalled by the calculated flirtation with default. It has seriously diminished Republican chances of recapturing control of the Senate in 2014, which looked like a real possibility before the latest crisis. They’re not going to try this tactic again.

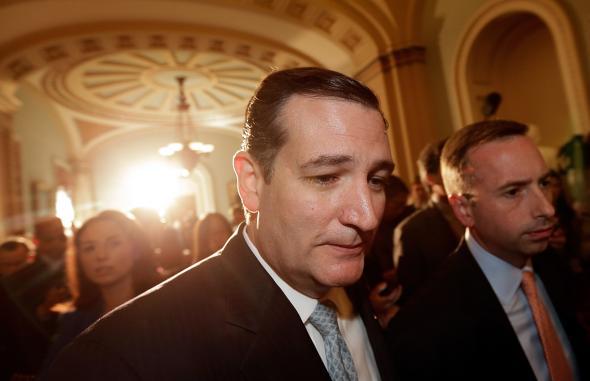

But for many Republican politicians, the incentives remain unchanged. Texas Sen. Ted Cruz has done great harm to his party by instigating the showdown over Obamacare, but in the process he made himself into a national celebrity and the darling of the right. Many House Republicans will be home in their districts this weekend, bragging that they voted against the sell-out. In the mid-term election of 2014, no ultraconservative Republican is likely to face a moderate primary challenger with interest-group support and outside funding.

What the GOP needs to become a serious governing party again is a set of countervailing incentives and rewards to support what were once its cardinal virtues: respect for tradition and process, aversion to radical change, and willingness to compromise. For the moment, however, the Tea Party remains its dominant force—soundly beaten in this round to be sure, but unbowed, unrepentant, and still deliriously irresponsible.

A version of this article appears in the Financial Times.