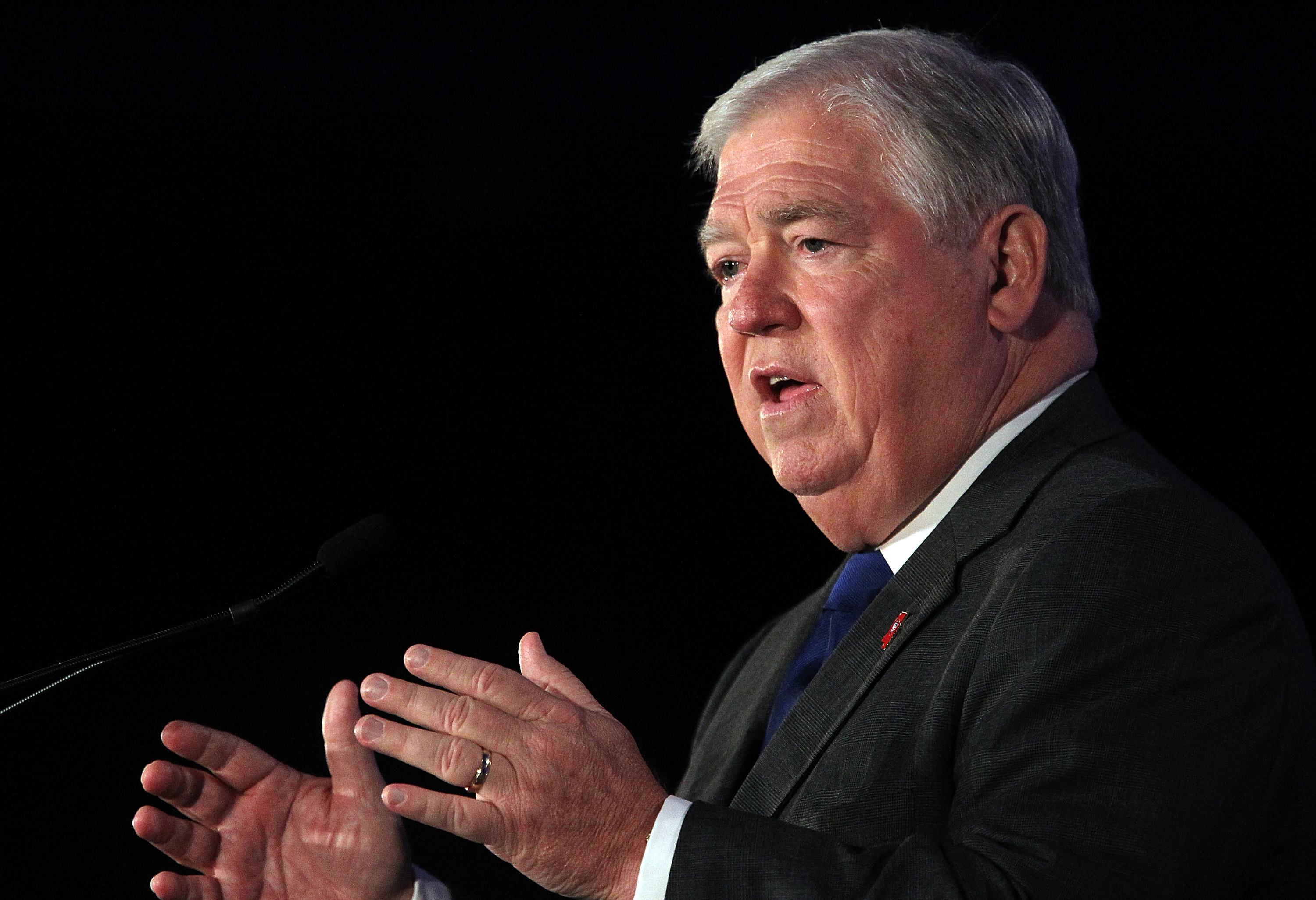

It’s a funny thing about Washington: Everyone complains about it, but no one ever seems to leave. Take former House Majority Leader Richard Gephardt. The Missouri Democrat twice ran for president as a voice of organized labor. Today he pockets $7 million a year to lobby on behalf of corporate clients and advise them on busting unions. Or consider former journalist Jeffrey Birnbaum, who used to write exposes of the lobbying trade for the Wall Street Journal. Today he works for Haley Barbour, the fattest of Republican fat cats.

Such fables of political principles discarded, betrayed, or rented by the hour fill the pages of Mark Leibovich’s alarming and amusing new book, This Town. Leibovich captures the Gilded Age atmosphere of a capital where influence has been commoditized and marketed as never before. It’s a gallery of rogues—some charming, some merely roguish—who flourish as the capital’s fundraisers, fixers, party-givers, and talking heads. These people come together in a mutual advancement society where personal beliefs are no obstacle to green room friendships, like the one between gay marriage advocate like Hilary Rosen and biblical literalist Ralph Reed, who perform the same lobbying work by day.*

Leibovich has little to say, however, about elected Washington, which has trended in precisely the opposite direction in recent years. This other town is characterized by inflexible ideology and irreconcilable conflict. The recurring hostage drama around the federal budget and debt ceiling is driven by zealots whose mission is to cut Washington down to the size of the 1950s, the 1920s, or the 1820s. Official Washington has precisely the opposite flaws of unofficial Washington: It is too stubbornly principled, too worried about corruption, and too contemptuous of those it disagrees with.

This Washington is well depicted in another recent book, Do Not Ask What Good We Do by the journalist Robert Draper. On issues like climate change and immigration, the Tea Party caucus Draper portrays believes that searching for a solution itself constitutes the problem. These patriotic anarchists refuse to accept the basic legitimacy of laws and decisions they disagree with, whether Obamacare or Roe v Wade. They use the filibuster to prevent anyone from ever filling posts involving the enforcement of gun laws or environment regulation. As we are about to experience once again, they’re prepared to shut down the entire federal government if they do not get their way. They don’t think anyone will miss it, except for the Pentagon.

These two contradictory Washingtons are both correct about one thing—each other. Official Washington is on the mark in its contempt for a parasitic class that cares about nothing and inflates the cost of everything Washington does. Unofficial Washington is accurate in its view of the Tea Party as nativist yahoos who don’t appreciate that democracy requires dealmaking and compromise.

Yet, rather than being on a collision course, these two Washingtons have become curiously symbiotic. The Tea Party makes sure there’s no shortage of political ranting to fill the cable channels. Young congressional staffers, meanwhile, see profitable futures at lobbying firms after a few years on government salaries. By a magical process of acculturation, Washington transforms true believers into members of the stay-and-get-rich club. One-half of former senators, and nearly as large a share of former House members, stay on as lobbyists after leaving office.

What drives this process, to which both parties are subject, is the dazzling amount of money to be made in the neighborhood of politics if you don’t work for the government. The biggest change in Washington over the past 30 years is that social status there used to depend more on proximity to power than upon wealth. This wasn’t necessarily a superior value system, but it did create a distinctive culture in which the city’s richest people weren’t treated as its most important people. Now Washington is America’s wealthiest city and has the same value system as every other.

Leibovich and Draper offer little by way of ideas how to fix the metropolis they depict so damningly. It’s not clear there is any way to fix it. Official Washington’s problem is primarily structural: State-level gerrymandering produces 30-sided congressional districts that favor extremists over moderates. Unofficial Washington’s problem is ethical: An older conception of public service has given way to the pursuit of wealth and personal advantage. The result is a double knot of dysfunction that won’t be untangled anytime soon.

A version of this story also appears in the Financial Times.

Correction, Aug. 12, 2013: This article originally misspelled Hilary Rosen’s first name.