The five conservative justices on the Supreme Court—Thomas, Alito, Scalia, Roberts and Kennedy—cloak themselves in the myth that they are somehow channeling the wisdom and understanding of the Founding Fathers, the original intent that guided the drafting of the Constitution. I believe the premise of their argument is itself suspect: It is not clear to me how much weight should be given to non-textually based intent that is practically impossible to discern more than 200 years later. Most of the issues over which there is constitutional dispute today could not even have been envisioned when the document was drafted.

Even so, it would be an even better response to the conservative wing’s claim of perceived understanding of original intent to be able to refute their claims by showing them to be historically and indisputably wrong. So once again let’s venture into the world of the health care debate. The consensus view is that existing Commerce Clause doctrine clearly authorizes the type of mandate passed in the act—see in particular the affirmance of the statute by ultraconservative Judge Silberman of the D.C. Circuit Court.

Nonetheless, those opposing the bill insist that an individual mandate has never been done and the framers would simply not permit such an encroachment on liberty and freedom.

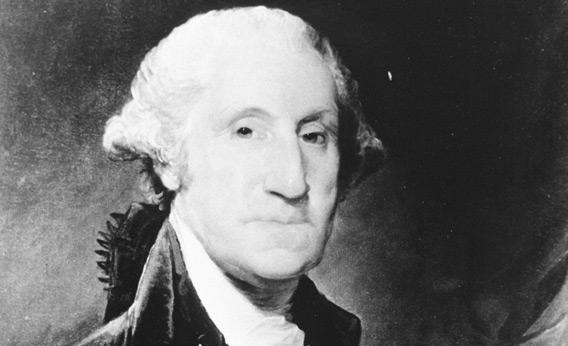

Some spectacular historical reporting by Professor Einer Elhauge of Harvard Law School in the New Republic thoroughly rebut the argument. He has found three mandate equivalents passed into law by the early Congresses—in which a significant number of founders served—and reports that these bills were signed into law by none other than Presidents George Washington and John Adams. As Founders go, one might consider them pretty senior in the hierarchy. Their acts can probably be relied upon to give us a reasonable idea what the Founders intended to be the scope of congressional and governmental power.

Amazingly, the examples of individual mandates passed by the founders are so directly applicable that the claim that original intent precludes affirming the heath care act should become almost laughable:

- In 1790, a Congress including 20 Founders passed a law requiring that ship owners buy medical insurance for their seamen. Washington signed it into law.

- In 1792, another law signed by Washington required that all able-bodied men buy a firearm. (So much for the argument that Congress can’t force us to participate in commerce.)

- And in 1798, a Congress with five framers passed a law requiring that all seamen buy hospital insurance for themselves. Adams signed this legislation.

In aggregate, these laws show that the Founders and the Congress of the time were willing to force all of us to participate in a particular act of commence and were comfortable requiring both the owner of a business and the individual employee to buy insurance in order to assure that health costs would be covered at a societal level. That is a pretty complete rebuttal to all the claims being made by the originalists as they relate to the health care act.

But what is so powerful about these historical finds is not just that they rebut the specific argument about original intent as applied to the health care act. This history lays bare the ahistorical nature of the justices’ claims at another and deeper level. For the types of bill passed in 1790, 1792, and 1798 show the Founders to have been doing exactly what congress did especially well in the era of FDR—–experimenting with solutions and approaches to resolving social issues in ways that made government part of creative problem solving.

These examples show the fallacy and the false rigidity that the originalists seek to impose on our government. In their effort to cabin and restrain the government—their ideology of the moment—they seek to have the benefit of the claim that the founders shared such a limited approach to governing. In fact, the approach to governing that these acts demonstrate is more nuanced and thoughtful. As with so many of the claims of the originalists, a slight understanding of the true history shows that the originalists’ view is mere ideology being imposed on a false understanding of history.