Two big themes emerge on Wednesday in McDonnell v. United States, the appeal of former Virginia Gov. Bob McDonnell of his felony public corruption conviction. The first is that if lawyers across ideological lines agree that McDonnell was wrongly convicted under a vague and unfair ethics statute, they must be correct. As Chief Justice John Roberts notes in one of his first questions to Deputy Solicitor General Michael Dreeben—arguing in favor of sending McDonnell to prison to serve his two-year sentence—an “extraordinary document was filed by former federal officials from every administration, all in support of McDonnell.” They argue, says Roberts, that “if this decision is upheld, it will cripple the ability of elected officials to fulfill their role in our representative democracy.”

Which brings us to the other big theme: It seems obvious to the justices that public corruption and ethics rules are adorable, antiquated, and unenforceable because everybody does it. Dreeben’s response to Roberts’ question about the “extraordinary” strange bedfellows supporting the opposing side points to the depressing endpoint of this logic. Under McDonnell’s attempt to define corruption down with his appeal, Dreeben says, “[This] theory of governance really is that people can pay for access, that they can be charged to have a meeting, or have a direction made to another government official to take the meeting.”

But if everyone already does it? Well, then it’s possible that’s not corruption and that everyone but Dreeben got the memo.

McDonnell and his sort-of-sometimes wife, Maureen, were convicted in 2014 of public corruption, charges stemming from $177,000 in Dynasty-era gifts (de la Renta/Rolex), luxury vacations, Ferrari joy rides, and loans they accepted from Jonnie R. Williams Sr. The former CEO of the company Star Scientific, Williams was a wealthy Virginia businessman who wanted the First Couple to promote his tobacco-based dietary supplement business, Anatabloc.

Virginia state law did not prohibit such gifts so long as they are disclosed, and the couple did not face criminal prosecution from the state. As a result of the federal case, though, McDonnell was convicted on 11 corruption charges and sentenced to two years in prison; Maureen was sentenced to a year and a day. McDonnell lost his appeal at the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in a unanimous decision, but the high court granted him reprieves from beginning to serve his sentence and decided to hear his case.

McDonnell is urging that the definition of having done “official actions” in exchange for gifts under the Hobbs Act and the honest services statute be limited to exercising actual governmental power or pressuring others to use government power. The Hobbs Act was established in 1946 and has been used to criminalize acts of robbery or extortion that affect interstate commerce, basically the equivalent of bribery. The honest services statute used to apply to a broad range of fraud, but in 2010 in Skilling v. United States, the Supreme Court limited the statute to bribery or kickbacks.

McDonnell’s lawyer Noel Francisco argues that “an official must either make a government decision or urge someone else to do so” and not just throw a fancy reception or ask someone to take a meeting in order for there to be actual corruption under these statutes.

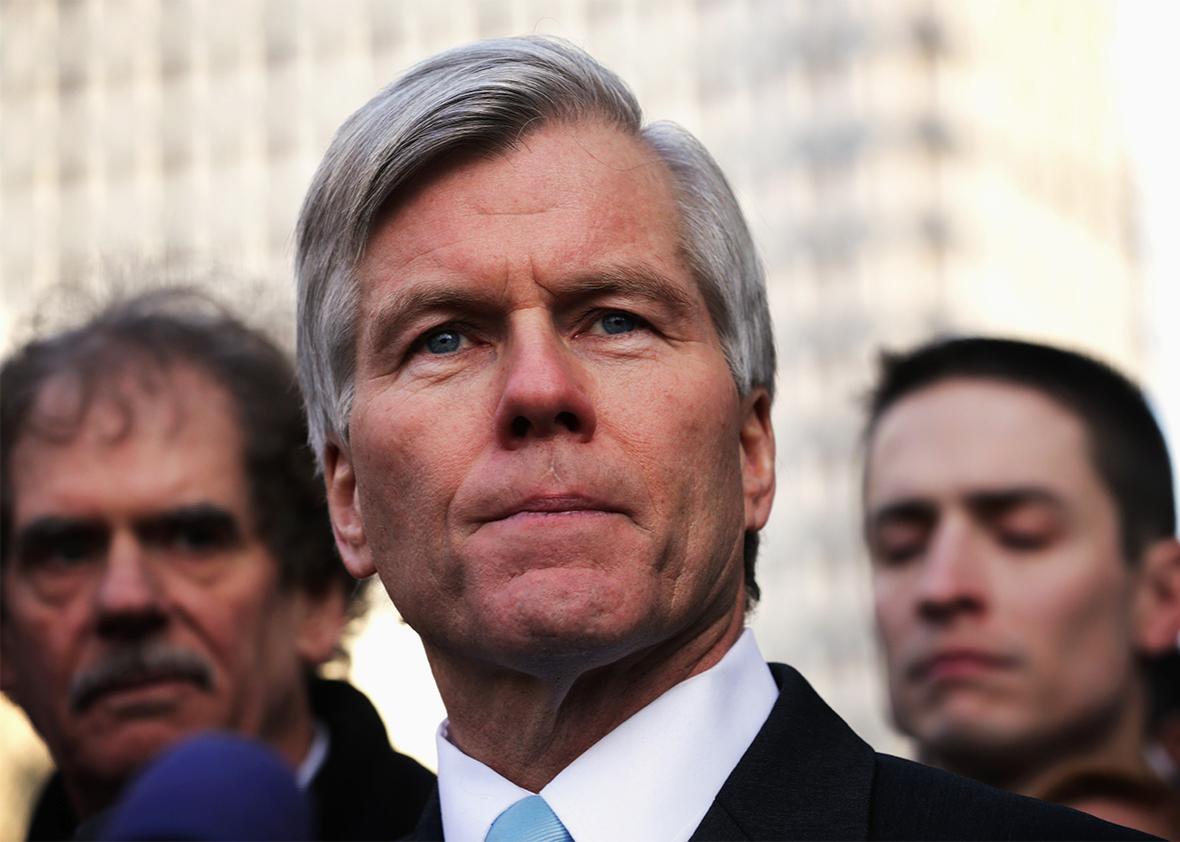

The former governor sits in the second row, looking gubernatorial, next to Maureen and one of his daughters. Almost all of the justices pepper Francisco with questions about where that line of corruption between merely enabling meetings and urging specific outcomes is found. Justice Elena Kagan inquires whether contractors bidding for a billion dollar government project can pay to sit in on a meeting with officials determining who gets the contract; Justice Samuel Alito asks if a contractor could pay to sit in a staff meeting for a chat; Justice Sonia Sotomayor asks whether it matters that officials at the two state universities that Williams wanted to run clinical trials on Anatabloc actually felt pressured by the governor to invite him to do so. Francisco replies that none of the offenses constitute official acts “because in none of them did Gov. McDonnell cross that line in trying to influence the outcome of any particular decision.” McDonnell may have had a “bully pulpit,” but he couldn’t force anyone to run clinical trials.

Justice Anthony Kennedy appears somewhat skeptical, asking whether an “official action” isn’t the same as an “exercise of governmental power?” No, replies Francisco: “If you’re simply setting up a meeting so that somebody can appeal to the independent judgment of an independent decision maker, and you’re not trying to put your thumb on the scale of the outcome of that meeting, then that simple referral can’t possibly be official action.”

Justice Stephen Breyer says he is seeking “a set of words that will describe … the criminal activity involved.” Francisco replies it should be “an attempt to influence.”

Breyer goes ballistic at this. “You want to use ‘attempt to influence?’ My goodness,” Breyer says, noting that government officials receive letters from elected officials all the time attempting to influence outcomes on behalf of supportive constituents, which doesn’t necessarily result in action or corruption. “And then the elected official says to [the constituent], ‘I did my best on this.’ And [the constituent] thinks, ‘good, he’s used his influence.’ … A crime?? My goodness!” Two my goodnesses are a sign that Breyer thinks this cannot be a felony.

Then it’s Dreeben’s turn to field questions about Things Everyone Does.

“If the president gives special access to high-dollar donors to have meetings with government officials, that is a felony?” Kennedy asks. Dreeben says not without a quid pro quo.

Justice Breyer says that he cannot support this reading. His concerns are twofold. First, using the criminal law to go after this conduct is unwise because politicians won’t be able to figure out what’s allowed and not allowed due to “a general vagueness problem.” His second concern? Breyer worries the Department of Justice will have too much power in determining what is and isn’t corruption for officials across the country. “As you describe it,” he says, “for better or for worse, it puts at risk behavior that is common, particularly when the quid is a lunch or a baseball ticket …”

Dreeben is trying to answer, but Breyer is on a roll. He asks Deeben the same question he asked Francisco: What are the actual words to define “official actions?” He also issues a caution: “I’ll tell you right now if those words are going to say when a person has lunch and then writes over to the antitrust division and says, ‘I’d like you to meet with my constituent who has just been evicted from her house,’ … if that’s going to criminalize that behavior, I’m not buying into that, I don’t think.”

Dreeben suggests that among other things, the standard for conviction for such crimes is guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. “But then this doesn’t answer Justice Breyer’s basic question and ours,” Kennedy scoffs. “You’re going to tell [officials] ‘Don’t worry, the jury has to be convinced beyond a reasonable doubt.’ And that’s tough?”

So on it goes, with Roberts wondering why it’s OK to take your senator trout fishing but not OK to take him to Hawaii? Even Kagan expresses doubts over the federal government’s case. When several justices suggest that maybe the wording of the statute is unconstitutionally vague, Dreeben—arguing his 100th case before the court—appears gobsmacked: “I think it would be absolutely stunning if this court said that bribery and corruption laws, which have been on the books since the beginning of this nation and have been consistently enacted by Congress to combat both federal, state, and local corruption …”

But Kennedy interrupts him: “The government has given us no workable standard.” The real problem, however, is not that the standards are unworkable. The problem—as Justice Antonin Scalia used to complain of privacy standards—is that these standards keep shrinking as our expectations around them shrink. As the corruption bar gets lower, maybe the people who are only worried about getting busted—those who anxiously watched the prosecutions of Bob McDonnell, or Don Siegelman, or Rod Blagojevich—also shouldn’t be the arbiters of corruption. Especially since they keep saying that it can’t be corruption if everyone else does it.

It will be an amazing thing if—in a year when voters across the spectrum are infuriated and sickened by the influence of money in politics—the Supreme Court decides that poor Bob McDonnell should be let off the hook because he only did what every politician does every day: Take a lot of money to open doors for a rich guy. But maybe the line between money and influence is too fuzzy and ubiquitous to even be said in words anymore.