Read all of Slate’s coverage about the Affordable Care Act.

The fight over Obamacare is about freedom. That’s what we’ve been told since these lawsuits were filed two years ago, and that’s what we heard both inside and outside the Supreme Court this morning. That’s what Michele Bachmann* and Rick Santorum have been saying for months. Even people who support President Obama’s signature legislative achievement would agree that this debate is all about freedom—the freedom to never be one medical emergency away from economic ruin. What we have been waiting to hear is how members of the Supreme Court—especially the conservative majority—define that freedom. This morning, as the justices pondered whether the individual mandate—that part of the Affordable Care Act that requires most Americans to purchase health insurance or pay a penalty—is constitutional, we got a window into the freedom some of the justices long for. And it is a dark, dark place.

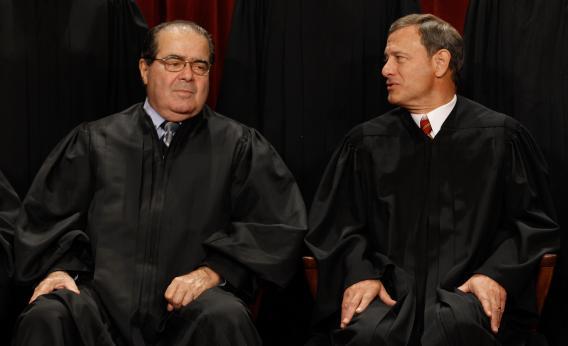

It’s always a bit strange to hear people with government-funded single-payer health plans describe the need for other Americans to be free from health insurance. But after the aggressive battery of questions from the court’s conservatives this morning, it’s clear that we can only be truly free when the young are released from the obligation to subsidize the old and the ailing. Justice Samuel Alito appears to be particularly concerned about the young, healthy person who “on average consumes about $854 in health services each year” being saddled with helping pay for the sick or infirm—even though, one day that will describe all of us. Or as Justice Antonin Scalia later puts it: “These people are not stupid. They’re going to buy insurance later. They’re young and need the money now.” (Does this mean that if you are young and you pay for insurance, Scalia finds you “stupid”?)

Freedom also seems to mean freedom from the obligation to treat those who show up at hospitals without health insurance, even if it means letting them bleed out on the curb. When Solicitor General Donald Verrilli tries to explain to Justice Scalia that the health care market is unique because “getting health care service … [is] a result of the social norms to which we’ve obligated ourselves so that people get health care.” Scalia’s response is a curt: “Well, don’t obligate yourself to that.”

Freedom is the freedom not to rescue. Justice Kennedy explains “the reason [the individual mandate] is concerning is because it requires the individual to do an affirmative act. In the law of torts, our tradition, our law has been that you don’t have the duty to rescue someone if that person is in danger. The blind man is walking in front of a car and you do not have a duty to stop him, absent some relation between you. And there is some severe moral criticisms of that rule, but that’s generally the rule.”

Freedom is to be free from the telephone. Verrilli explains that “telephone rates in this country for a century were set via the exercise of the commerce power in a way in which some people paid rates that were much higher than their costs in order to subsidize.” To which Justice Scalia is again ready with a quick retort: “Only if you make phone calls.” Verrilli tries to point out that “to live in the modern world, everybody needs a telephone,” but that assumes facts not in evidence.

Freedom is the freedom not to join a gym, not to be forced to eat broccoli. It’s the freedom not to be compelled to buy wheat or milk. And it’s the freedom to purchase your health insurance only at the “point of consumption”—i.e., when you’re being medevaced to the ICU (assuming you have the cash).

Some of the members of the court find this notion of freedom troubling. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg notes that: “Congress, in the ‘30s, saw a real problem of people needing to have old age and survivor’s insurance. And, yes, they did it through a tax, but they said everybody has got to be in it because if we don’t have the healthy in it, there’s not going to be the money to pay for the ones who become old or disabled or widowed. So, they required everyone to contribute. There was a big fuss about that in the beginning because a lot of people said—maybe some people still do today—I could do much better if the government left me alone. I’d go into the private market, I’d buy an annuity, I’d make a great investment, and they’re forcing me to paying for this Social Security that I don’t want. But that’s constitutional.”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor invokes government tax credits for “solar-powered homes and fuel-efficient cars.” Paul Clement, representing the 26 states challenging the health care law, replies to explain how the Framers would have thought about taxing carriages. The analogy of taxing carriages probably makes perfect sense to the court’s conservatives, who likened GPS devices to tiny constables in this year’s GPS case. We seem to be talking across the centuries once again in this room, and the days of leeches are looking pretty darn dreamy for some. Sotomayor says, “There is government compulsion in almost every economic decision because the government regulates so much. It’s a condition of life.” But one gets the sense that not everyone acknowledges the reality of that life, much less approves of it.

Sotomayor, again pondering whether hospitals could simply turn away the uninsured, finally asks: “What percentage of the American people who took their son or daughter to an emergency room and that child was turned away because the parent didn’t have insurance—do you think there’s a large percentage of the American population who would stand for the death of that child if they had an allergic reaction and a simple shot would have saved the child?”

But we seem to want to be free from that obligation as well. This morning in America’s highest court, freedom seems to be less about the absence of constraint than about the absence of shared responsibility, community, or real concern for those who don’t want anything so much as healthy children, or to be cared for when they are old. Until today, I couldn’t really understand why this case was framed as a discussion of “liberty.” This case isn’t so much about freedom from government-mandated broccoli or gyms. It’s about freedom from our obligations to one another, freedom from the modern world in which we live. It’s about the freedom to ignore the injured, walk away from those in peril, to never pick up the phone or eat food that’s been inspected. It’s about the freedom to be left alone. And now we know the court is worried about freedom: the freedom to live like it’s 1804.

Dahlia Lithwick will be chatting with readers on Facebook about this week’s Obamacare oral arguments at 10 a.m. ET on Thursday, March 29.

*Correction, March 28, 2012: This article originally misspelled Michele Bachmann’s last name.